Log on to the AFL’s official match centre and you’ll find not only which games are coming up but also the odds for each side offered by “major partner” Sportsbet. You can toggle the odds on and off, and they’re hidden if you admit to being under eighteen, but the default layout features the potential payout on a $1 bet for every team in every match. A click on the odds leads straight to Sportsbet, and if you make a bet, the AFL gets a cut.

Sportsbet also “partners” with Foxtel and the Seven Network for their AFL broadcasts and weekly commentary shows. Seven’s The Front Bar, for example, features comedian Mick Molloy’s “multi” — a recommended punt on the performance of four players from four different teams.

This deep interweaving of gambling and sport is generating social media abuse and even death threats for players whose on-field performance fails to pay off for punters. But there is a deeper problem: according to a new American study, sports betting is breeding scepticism about fairness in sport in general by “predisposing viewers to interpret routine player or referee error as evidence of a fix.”

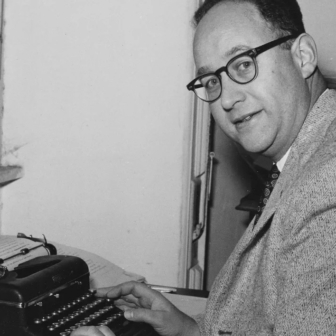

Jonathan D. Cohen’s Losing Big: America’s Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling makes for fascinating and alarming reading. Because the American sports betting industry grew suddenly and rapidly after the Supreme Court gave it the green light seven years ago, the United States provides a vivid case study of the damage it can cause.

Back in 1992, with overwhelming support from both houses of congress, president George H.W. Bush signed a law that prevented any government entity from authorising betting operations based on professional or amateur sports. Two and a half decades later, in 2018, America’s highest court declared the law an unconstitutional infringement of states’ rights.

Within six years, thirty-eight states had approved sports betting; soon, one in five American adults was gambling on sport. By 2023, the annual spend was US$121 billion, more than Americans outlaid that year on movies and video games combined. Since gamblers win back, on average, just 90 per cent of the money they wager, their collective losses were around US$12 billion.

The US industry is dominated by two global companies, FanDuel and DraftKings, which control 75 per cent of the market. FanDuel is owned by Flutter, parent company of Sportsbet, Paddy Power and Betfair, all prominent firms in the Australian market. As far as I can ascertain, DraftKings is not currently active in Australia.

Just like the AFL, US sporting codes seized the opportunity to open up betting in all its forms. Gambling promised not only extra revenue from sponsorship deals, licensing agreements and data sharing (of player stats, for example) but also a way to bump up flagging ratings.

The National Football League justified its embrace of gambling as way to foster “fan engagement.” Cohen says gambling companies wanted to get fans into the habit of keeping their app open while they watch games, normalising betting as “part of the sports viewing experience.” The NFL doesn’t seem to mind, he says, “if it becomes as normal to bet on football as it is to watch football.”

US sporting clubs and gaming companies argue that if the Supreme Court hadn’t legalised betting in 2018, fans would have gambled just as much through illegal bookmakers and offshore websites without bolstering state revenues. But data shows that many Americans only started betting on matches after it became legal and was aggressively promoted by sporting codes and gambling companies, often with endorsements from former star players and other celebrities.

The only way to lure people away from unauthorised gambling, the companies say, “is to advertise everywhere, to offer innumerable ways to bet, to provide generous promotions, and so on.”

“Kyle,” who lost hundreds of thousands of dollars betting on sport, tells Cohen he’s certain he would never have run into trouble if online betting hadn’t been made legal. Another big-time loser “Andrew,” says “the devil is in your hand” — a reference to his mobile phone.

“There have always been Americans driven to ruin by gambling,” writes Cohen. “But never have so many been driven to ruin so easily, and never has government done so much to enable them to gamble.” Ease of gambling by phone makes sports betting especially risky: “Online sports betting offers almost no friction, providing little to encourage players to slow down and take stock of their play.”

The late Labor MP Peta Murphy made the same point in her foreword to a 2023 parliamentary committee report on online gambling. “It is easier now than ever before to lose big with a few taps on a mobile phone,” she wrote. “Online gambling is unlike other forms of entertainment because of its potential to cause psychological, health, relationship, legal and financial harm to individuals and those around them, and tragically, gambling is a key risk factor for suicide.”

There are strong parallels with the long-running debate about poker machines. Evidence shows that if pokies are readily available then gambling losses mount, often among those who can least afford them — a fact made clear by the Productivity Commission’s landmark inquiry into Australia’s gambling industry back in 1999.

By comparing Victoria and New South Wales, the commission drew a strong link between easy access to gaming machines and rising losses. Until 1987–88, Victorians lost less than $1 billion each year to gambling, about 40 per cent of the amount lost north of the border. A decade later, the Victorian figure was $3 billion, or about 70 per cent as much as in NSW. The difference? The Victorian government legalised poker machines in 1991 and they spread rapidly through pubs and clubs.

Another significant finding by the commission was that gambling in general is only profitable because a small share of punters lose large sums of money. It found that 10 per cent of gamblers accounted for around 70 per cent of the $11 billion lost on all forms of gambling in 1997–98. More than half that money was lost on the pokies, where 42 per cent of revenue was estimated to come from “problem gamblers.” (Researchers now avoid that term because it blames the individual rather than how gambling is organised.)

As with the pokies, Cohen maintains that sports betting’s profits in the United States don’t come from casual bettors but from the 5 per cent of people — like Kyle and Andrew — who provide 70 per cent of the total gambling spend. “The industry is built not on the discretionary income of the well-to-do but on the dollars and dreams of people who are addicted or who are gambling money they cannot afford to lose.” The Australian evidence paints a similar picture.

Cohen sees sports betting as especially risky for young men, who imagine it as an exercise in intelligence rather than a game of luck with rigged odds. “Many sports fans — especially young men — feel they have a unique understanding of the games they watch,” he writes. “When their intuition is wrong, these same fans have a remarkable ability to maintain their confidence, convinced that their wins are the result of their knowledge of the game and their losses are due to unlucky bounces.”

This chimes with Australian data. A study based on the most recent HILDA survey found that sports betting by young Australian men jumped by more than 60 per cent between 2015 and 2022. The average amount bet each month also grew sharply.

This presages a scary future. The Australia Institute reckons teenagers are already more likely to gamble than to play any of the sports popular in their age group. Its analysis of recent studies found that 30 to 40 per cent of twelve- to seventeen-year-olds gamble, admittedly in small amounts, and that rates and stakes jump sharply when young people turn eighteen and betting becomes legal — but don’t decline when they enter their twenties.

While boys and young men may be most at risk, Deakin University researchers warn that women and girls also gamble in large numbers and are being targeted as betting companies seek to expand their reach. As well as sponsoring women’s sports, the companies offer bets on “novelty markets” including popular TV shows such as Married at First Sight, Love Island and White Lotus. The tagline in a TikTok promotion featuring a young woman reads “Sportsbet has a market for everyone.”

Cohen’s book paints a bleak picture of the ravages of gambling in the United States, but in fact Australians are the world’s biggest losers. Equity Economics found that a record $31.5 billion was lost to gambling in 2022–23, an average loss of about $2500 per gambler and a 25 per cent increase on pre-Covid levels. (Losses diminished during the pandemic because gambling venues were closed and sporting events suspended.) Despite inflation exacting a heavy toll on household budgets, gambling losses ranked higher than energy bills as a share of average household spending.

Other studies show that even though a smaller proportion of Australians are gambling, turnover has not declined. Regular gamblers appear to be betting more frequently and for higher stakes, a phenomenon researchers call “intensification.”

After three years in office, one of Labor’s biggest unfulfilled promises is tighter regulation of sports betting and other forms of online gambling. According to Age political reporter Paul Sakkal, Anthony Albanese overruled communications minister Michelle Rowland’s plans to block online gambling ads, cap the number of TV ads before 10pm at two per hour, and ban ads an hour before and after live sport.

The prime minister was reportedly worried by the likelihood of a backlash from sporting codes, gambling companies and media interests in the run-up to the election, and especially from AFL rights owner, Seven West Media, which dominates news reporting in the crucial state of Western Australia.

In evidence to the inquiry chaired by Peta Murphy, media organisations claimed (without hard evidence) that the revenue flowing from gambling ads was essential to the commercial viability of free to air sport broadcasts. The committee gave this argument short shrift, pointing out that the same arguments had been used decades earlier to resist restrictions on tobacco advertising. “It is a shame that harmful industries appear to gain so much leverage over sports and media organisations,” said the committee.

Albanese also feared — probably rightly — that a partial advertising ban would fail to quell criticism from the Greens, independent MPs and other advocates for stricter gambling controls because they were unlikely to be satisfied with anything less than the complete ban unanimously called for by Murphy’s committee. (The committee recommended the ban be phased in over three years to give sporting codes and broadcasters time to find alternative sources of revenue.)

If the election results in a minority Labor government, Albanese will be forced by the Greens, independents and his own backbenchers to think again. And while advertising is the big-ticket item that has attracted public attention, stronger and finer-grained controls are also needed.

The current “responsible gambling” approach has clearly failed. We know that product warnings — “What are you really gambling with” or “Chances are you’re about to lose” — have little effect on behaviour. The US has adopted the same approach, and as Cohen writes in Losing Big, messages like these are exactly what gambling companies want. They embrace responsible gambling because it “reinforces to bettors that playing safely is up to them — and them only.”

As Monash University public health researcher Charles Livingstone points out, “little if any attention is devoted to the environment in which gambling is available” or to “examining the nature of gambling products.” It is quite possible to design much safer poker machines, for example, by restricting the amount that can be lost per hour, but that would make the machines far less profitable.

The same applies to the betting apps on mobile phones. Gambling companies use the “design of the app interfaces, the nonstop stream of betting options, the relentless advertising, and the auspiciously timed bonus offers… to keep people like Kyle engaged, maximising their ‘customer lifetime value.’” No American gambling regulators have gone so far as to restrict the design of betting interfaces or drastically limit betting options, and there has been little discussion of these issues in Australia.

Cohen says gambling operators have plenty of customer data to identify risky betting but choose not to do so. In fact, they are more likely to ban successful professional gamblers who regularly beat the house than amateurs who lose their shirts.

US sports bettors can voluntarily set limits on their play by restricting the time spent online or the amount they bet or deposit into their account, but DraftKings reports that only a tiny fraction does so in its home state of Massachusetts — just 0.1 per cent set a time limit and 0.13 per cent a spending limit.

“These tools are, fundamentally, the wrong way to protect players,” says Cohen. Limiting the amount that a gambler can deposit into their online betting account isn’t necessarily the most promising approach because the best indicator of risky behaviour is not so much the size of deposits as their frequency. Gamblers who are in trouble often make repeated small deposits to chase their losses, for example, and smaller deposits are less likely to be noticed in shared bank accounts.

Instead, Cohen wants to see gambling companies made liable “if they allow someone with an obvious gambling problem to continue betting and that person commits a financial crime to keep up their habit.” He commends Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands for limiting weekly or monthly deposits for online betting.

The companies have the capacity to act, but they only do so under pressure. In 2021, for example, as the British government moved to review gambling regulations, Sportsbet’s parent company Flutter set a monthly deposit limit of £500 (A$1000) for UK customers under the age of twenty-five. If it’s a worthwhile idea, why doesn’t Sportsbet voluntarily implement similar restrictions in Australia?

Cohen recommends restricting the number of sports the authorised websites can offer odds on. Sportsbet, for example, offers odds on Czech table tennis, Turkish volleyball and darts in Portsmouth. “No one is watching Malaysian women’s doubles badminton at four in the morning hoping to make every moment more by placing a little money on the match,” Cohen comments — yet betting companies offer the temptation. Regulators could also force the companies to make payouts seamless but add additional steps to making bets or deposits.

Australia’s regulation is marginally tighter than in the United States. Here, gamblers can self-exclude from all authorised online betting apps via a national service called BetStop for which 40,000 people have registered. In the United States, gamblers would have to self-exclude from every operator in every state. Still, at least one gambling addict found BetStop easy to circumvent, and plenty of websites recommend betting sites outside BetStop that offer “bigger bonuses, better odds, and fewer restrictions than platforms on the register.”

This points to the likelihood that if the activities of authorised gambling firms like Sportsbet were restricted, then some punters would shift offshore — an argument the industry deploys against further regulation. But Cohen’s research shows that such claims are massively overblown. And he believes governments can crack down much more effectively on offshore operators too. (He cites a successful example of targeting their domestic payment processors for money laundering.)

If the next government is serious about gambling reform, then it should heed Cohen’s advice. The overarching goal for the nation should be a sports betting setup focused on the well-being of gamblers even at the expense of industry profits or tax revenue.

Neither Australia nor the United States has faced up to the long-term consequences of the embrace of legal sports betting — facilitated, in Cohen’s words, “by profit-hungry companies and revenue-hungry lawmakers.” •

Losing Big: America’s Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling

By Jonathan D. Cohen | Columbia Global Reports | US$18 | 192 pages