Dancing With Warriors: A Diplomatic Memoir

By Philip Flood | Australian Scholarly Publishing | $39.95

PHILIP FLOOD will always be a company man. One of Australia’s most distinguished former diplomats and public servants, he remains on his best diplomatic behaviour throughout this nevertheless at times surprisingly revealing memoir.

Flood, a former secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, was a capable and successful diplomat and public servant for more than fifty years. He was intelligent, hard-working, cautious and possessed of a steely determination as he pursued Australian foreign policy objectives in postings that included the United States, Indonesia, France and Britain and ran overseas aid and intelligence bureaucracies.

Flood always knew and kept his place in relation to the Coalition and Labor political leaders he served. “[I]t is always elected ministers – and ministers alone – who make policy decisions and answer for them publicly,” he declares early in this memoir. Hawke, Keating, Evans, Bilney, Howard and Downer are the warriors of his title. But he was their dancing partner and guide, and at times no doubt saved them from inglorious stumbles.

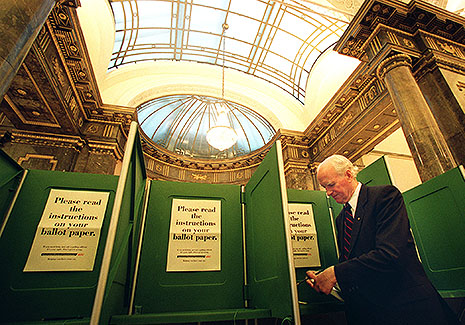

In places Flood’s memoir reads like an exercise in public diplomacy. It is inevitably a view from the top. He is an optimist, discreet, urbane, quick to praise, slow to criticise, always preferring to stress positives and to play down negatives, to seek out compromise, to avoid deadlock. But that is the DFAT company culture and it reflects Flood’s character and the inevitably covert ruthlessness that goes with it. (Flood, a keen, white-haired swimmer, was known by some in the department as the white shark.)

In a carefully nuanced analysis of a world that he describes as “scary,” Flood ultimately reveals himself to be a foreign policy realist focused on power and power relationships. He stresses the limits to multilateral United Nations internationalism. He offers sound but somewhat self-evident reasons for optimism about Australia’s future and a list of urgent needs including “a much larger population.” Darker pathologies lurking in national and international life are downplayed in the picture he paints.

Rather more surprisingly, he outs himself as a republican despite his seemingly boundless admiration for the British monarchy – especially Queen Elizabeth II – and the British way of public ceremony. It is a tribute to Flood that John Howard appointed him high commissioner to London knowing his republican sympathies (which were not public). He is also a champion of women’s rights and of the revival of Asian language studies in Australia.

At times you start to wonder how Flood could have served some fifty years at the top of the diplomatic, foreign aid and intelligence bureaucracies without running into any notable political or bureaucratic incompetents or bastards. Of course he did. He just doesn’t mention them or spend time settling scores – although he had little time for Billy McMahon, Yasser Arafat or the former PNG leader Julius Chan.

Most students of foreign policy will find his chapter on his role as ambassador to Indonesia the best part of the book. He understood the importance of the Australia–Indonesia relationship and was acutely sensitive to implications of the crisis triggered when Indonesian troops massacred one hundred or more East Timorese demonstrators in Dili’s Santa Cruz cemetery in 1991. Flood had built up superb contacts with Indonesian leaders including President Suharto, the diplomat and later foreign minister, Ali Alatas, and soldier and defence minister Benny Moerdani, and with key figures in East Timor. He quickly established that the Indonesian military and political leadership was lying about the massacre and he set about telling them that they had better come clean.

There seems little doubt that Flood was instrumental in forcing Indonesia’s eventual admission of enough of the truth about the killings to weaken its ability to hold onto the province. It was a diplomatic tour de force which earned Flood high praise from foreign minister Gareth Evans, never an easy man to please.

Flood subsequently headed Australia’s foreign aid agency (renamed AusAID on his watch) and the intelligence analysis agency, the Office of National Assessments, before serving as department secretary after Howard sacked Michael Costello. In this role he was immensely influential behind the scenes in bringing Howard and Downer up to speed on foreign policy, but discretion and adherence to diplomatic convention means that he maintains his silence on these issues. “[W]e should never underestimate how demanding is the task of political leadership, and how richly talented are those who aspire to its higher levels,” he writes.

Howard sent Flood to London just after Labor’s Tony Blair came to office in 1997. This son of an Englishman and closet republican who admired Britain and the Queen was, for staunch monarchist Howard, the ideal representative. In one of his last major diplomatic undertakings, Flood, his wife Carole and the High Commission staff set about organising the 2000 Australia Week celebrations to commemorate the anniversary of federation and the construction of the Australian War Memorial London. They were lavish, expensive occasions and there was considerable criticism of the cost as a shameless over-indulgence by the Howard government.

Flood, naturally, dismisses this criticism, ultimately citing praise from both Howard and Whitlam, a most unlikely pair, for the success of the occasion. In a sense, that bipartisan response neatly summarised this long career. •