John Newfong was excited when he was hired as a reporter on the Australian in 1971. The first Aboriginal journalist to work in the established print media, he would be learning from the renowned progressive editor Adrian Deamer, at a time when the fledgling paper’s reputation was growing.

Newfong was a general reporter who also wrote about Indigenous affairs. Deamer advised him to develop all-round skills so he would not be pigeonholed as writing only about being Aboriginal. At the end of July, however, the arrangement came to a sudden end when Rupert Murdoch sacked Deamer during a dispute over the direction of the newspaper.

Newfong was to be a secondary casualty: he was typecast by the new editors as an “Aboriginal writer” and there was no place for him in their plans. “John, I’m sorry but I don’t think there is going to be much here for you anymore,” a senior editor told him. That editor would tell this writer that the editor-in-chief “reckons Australians don’t want to read about black people.”

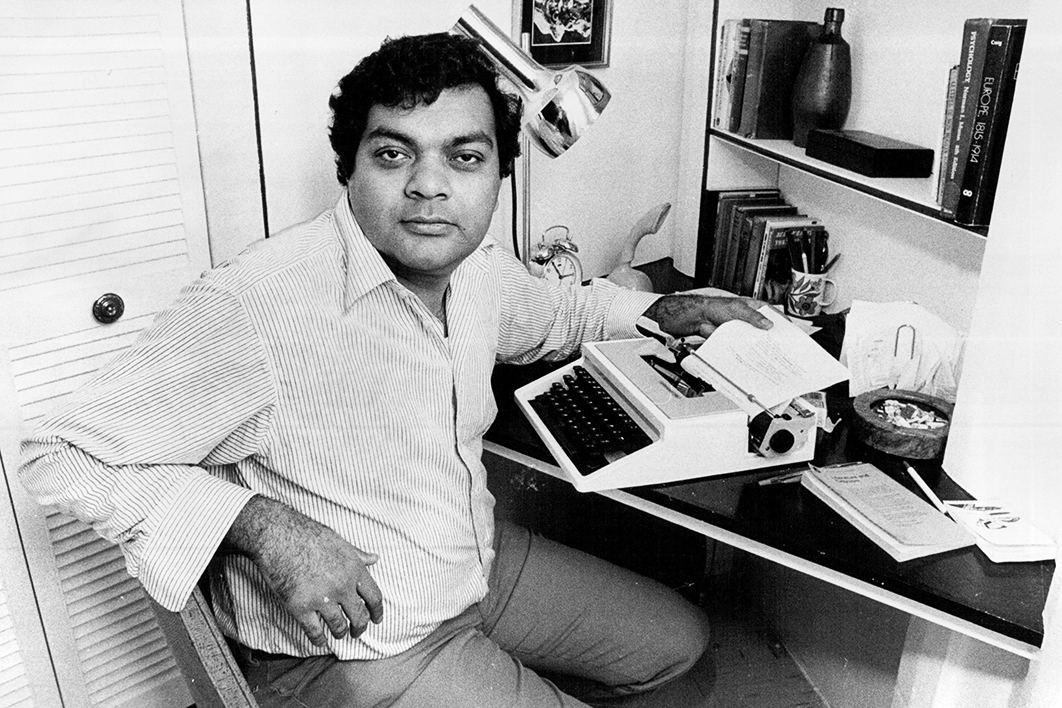

Newfong was well equipped to pursue a journalistic career. He was a precise and elegant writer with a sharp mind, an easy sense of humour, and a wealth of charm and warmth that inspired trust. His friend Lillian Holt, the first Aboriginal journalist to work for the ABC in Brisbane, says he had a rare quality. “It is called presence,” she says. “His entry into a space could not be ignored.”

Within two weeks of departing the Australian, Newfong was writing for the Bulletin. It seemed his career was still on a familiar track.

But it was not to be. There was a new stirring in Aboriginal affairs, led by what Dr H.C. (Nugget) Coombs called an Aboriginal intelligentsia — Black Power groups in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. Newfong was a key member of Sydney’s Redfern group.

For the rest of his life he was to fight for Indigenous rights and the improvement of Indigenous people’s lives using his journalistic and communications skills. He was to become a role model for young Aboriginal people in two ways: as a pioneering journalist and as the first openly gay Indigenous activist. He never “came out” because he had never hidden his sexuality. “I never knew a time when John was not openly gay,” Holt says. This personal integrity would underpin his journalism.

Newfong, a descendant of the Ngugi people of Moreton Bay, Brisbane, was born in 1943. His mother, Edna Crouch, played cricket for Australia in the 1930s; his father, Archie, was a champion boxer.

After leaving Wynnum State High School in 1961, Newfong nibbled at the edges of the media. He worked in the ABC mailroom in Brisbane; wrote TV reviews for Sydney’s Daily Mirror; studied typography and graphic design (as well as fashion); and worked as a newspaper proofreader.

Then came the breakthroughs: a cadetship at the Sydney Morning Herald in the 1960s and the job on the Australian.

Newfong’s involvement with Aboriginal affairs began straight after leaving school. He joined the student group; he worked with Victoria’s Aboriginal Advancement League and was particularly active in the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. He ran the council’s Queensland campaign for the 1967 Aboriginal citizenship referendum and in 1970 became its national secretary.

He made a mark as an activist in 1970 when he helped lead a protest against the Captain Cook bicentennial festivities. Aboriginal people, he said, had nothing to celebrate.

Two years later he played a crucial role in what may still be the most successful of Indigenous protests — the Aboriginal Tent Embassy opposite Parliament House in Canberra. The embassy, a demonstration against the McMahon government’s denial of Aboriginal land rights, was a Redfern Black Power protest. Newfong was its chief voice, lobbying and briefing journalists, politicians and diplomats. “The Mission,” he said, “has come to town.”

Newfong’s language was less strident than that of many of his radical contemporaries. In public statements, he shunned the “copulatory adjective.” Nevertheless, the point of view was the same.

In an ABC television interview, he said governments in power were indifferent to Aboriginal people. “Perhaps ‘indifference’ is being euphemistic,” he added. His defence of the embassy’s demands for land rights, mineral rights and financial compensation was calm but unyielding.

Newfong was appointed the first Aboriginal editor of the Indigenous magazine Identity in 1972. Melbourne University professor Marcia Langton says he made it enormously influential.

By 1975 he was doing public relations for the Redfern Aboriginal Medical Service. Langton remembers him returning to the office at night to help young Indigenous women produce the Aboriginal newspaper Koori Bina. “Working with John was a young writer’s dream,” she says. “He was extraordinarily well read, a brilliant analyst and writer [with a] supreme and ever-ready wit.”

Black Power waned as Newfong became a government adviser and speechwriter; public relations chief of the Aboriginal Development Commission; an adviser to the Australian Medical Association; a journalism lecturer at Queensland’s James Cook University; and a guest lecturer at several universities in Australia and overseas.

He also served on the board of the Public Broadcasting Foundation, helping spur the rapid growth of Aboriginal radio through support for Indigenous broadcasters. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, he contributed to a long list of publications.

He brought to his work a depth of knowledge, a strong analytical mind and a sharp sense of humour. His style was thoughtful and measured — but with clever, often angry barbs.

The pastoral industry, he once wrote, was “the black man’s burden”; Aboriginal protests threatened “the great Australian smugness”; and Indigenous claims for mineral rights made people worry about “us digging up their nondescript sprawls of suburbia.”

But he was to become disillusioned with the nature of government Aboriginal funding and the “ever-mushrooming Aboriginal bureaucracies.” Higher spending, he wrote, might merely result in “a whole new set of anagrams.” He wrote of Aboriginal bureaucrats “of the instant-coffee variety.” And in conversation he used the phrase nouveau noir to describe people who belatedly discovered their Aboriginality.

Newfong’s abiding concern was Indigenous health, highlighted in a fiery preface he wrote for the 1989 National Aboriginal Health Strategy. It is only six paragraphs long but it shows what a powerful writer and committed campaigner he was.

The first thing, he said, was to address the reality of Indigenous Australia, a reality obscured by white history and jingoism. Aboriginal people were “dressed in the hand-me-downs that are the legacy of dispossession and dispersal.” This was “a history forged in the cauldrons of colonisation.”

Newfong died in 1999, only fifty-five years of age. His legacy is honoured in New South Wales in the annual Kennedy Awards, named after the late Les Kennedy, an indefatigable crime reporter for News Corp and Fairfax newspapers. The prize for outstanding Indigenous affairs reporting is the John Newfong Award.

This is fitting, for Kennedy was also Aboriginal. When he began his career, he walked through the door John Newfong had nudged ajar. •