She walked into the room and he gave her a big hug, telling her how well she looked. After some discussion about how she had been coping he asked her to come and sit on his knee. She was very shocked. After a period of silence, he repeated the request in a “very authoritarian, quite demanding” tone. Ultimately she complied and sat on his knee. He put his hand on her leg, rubbing it up and down the inside of her leg and touching her crotch. She “just froze.” She was afraid of him and of what he might do to her. She told him that she “did not want to do this.” He did not respond. The incident lasted for “probably five minutes.” After this she got up and walked towards the door. He told her that he would need to see her again.

Dyson Heydon will likely recall this scene from his time on the High Court of Australia, and so might some of his associates. The sixty-three-year-old woman’s account of her first one-on-one consultation for post-natal depression thirty-three years earlier opened her psychiatrist’s 2009 trial in Perth. The following year, the national court granted Alan Stubley a last chance appeal against his conviction for multiple sexual offences against two of his patients. When he sat on the retired doctor’s case, Heydon was nearing the end of his decade on Australia’s top court.

Shortly after he was appointed to the High Court in 2003, according to the Sydney Morning Herald this week, Heydon “slid his hand” between the thighs of a “current judge” at a law dinner. She told him to “get your fucking hands off me.” Not long after he left the court in 2013, he attended a professional dinner where — according to the then president of the ACT law society — “his hands became very busy under the table, on my lap, feeling up the side of my leg.” He later asked her to discuss law in an empty room, where he hugged her and tried to kiss her. When she told him she was “definitely not interested,” he said “it would be such a wonderful encounter.”

These and other claims about a former High Court judge raise many questions. One is about his role in cases like Stubley’s. If the allegations against Heydon are true, then a serial predator of young women was asked to rule on an appeal by an alleged, if more extreme, serial predator of young women. We cannot know what thoughts crossed his mind as he read the testimony of Stubley’s patients. But we can read how he judged the psychiatrist. The answer is: harshly. Indeed, prosecutorially.

“To many people,” Heydon wrote in his judgement, the claim that a psychiatrist was preying on his patients “would seem so serious and inherently unlikely as to be startling, outlandish, and far-fetched to the point of being bizarre.” But “perhaps not all,” he allowed, citing those “afflicted with the cynicism characteristic of hard-bitten and experienced criminal lawyers.” Six years after he wrote those words, that same affliction became a global pandemic of sorts, fuelled by revelations of serial abuse by Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby and other celebrities, and thousands of other #metoo stories.

Heydon himself is now the subject of several such stories. The Sydney Morning Herald quotes a “leading female member of the NSW Bar” whose first thought when #metoo broke was, “Boy, Dyson Heydon should be really worried.” She goes on to describe Heydon inviting her to his chambers after she appeared before him at the High Court and, on a later occasion, kissing her while blocking her from leaving his room.

But in the less cynical times of Stubley’s appeal, Heydon was somewhat ahead of the public on whether to believe an allegation of professional predation. He bemoaned that such an allegation’s seeming bizarreness meant that a prosecution based on it alone “may easily falter, no matter how truthful,” even when — as Stubley’s patient testified — the allegation was of years of persistent indecent assaults and rapes perpetrated in a psychiatrist’s office, her sobbing throughout. That’s why, he said, such claims of predation shouldn’t be heard on their own.

Quoting Western Australia’s evidence law statute, he declared that “fair-minded people would think that that the public interest” would favour hearing “similar testimony about the tendency of the accused.” For example, he explained, Stubley’s trial featured charges arising from how he treated two of his patients, who each testified to repeated sex with the psychiatrist as part of their “treatment.” The second patient told the jury that Stubley had rubbed her breasts when she spoke with him about her stress at the breakdown of her marriage, and at a later consultation told her “I feel rejected” in a “very, very menacing tone.” “This is the most important relationship you will ever have,” he told her after they had sex on the floor of his office. A joint trial featuring both complainants, Heydon observed, “would be a prosecution supported by evidence of much greater probative value.”

The question the High Court had to decide in 2011 was whether the criminal justice system should go further to bolster prosecutions of alleged predators. Heydon, one of the world’s leading evidence scholars, ruled that it should. He endorsed Justice Narelle Johnson’s decision to allow several other patients of Stubley to testify at his trial in order to establish a pattern of predation. Each described sex on the floor of his office during emotional tumult: one had reached out to Stubley for an emotional but not sexual connection, another felt “embarrassed on his behalf” as he undressed in front of her, a third had unwanted sex out of fear that she would lose her job as his receptionist. Heydon ruled that “a prosecution supported by the evidence of three other women giving similar testimony about the tendency of the accused to engage in acts of sexual intimacy with patients during consultations” would be “of so high a degree of probative value” that “the public interest would have priority over the risk of an unfair trial.”

It is startling that Heydon used his judicial pulpit a decade ago to write something of a road map to his current predicament. Like Stubley, Weinstein and Cosby in some respects, he now faces allegations of predation that are greatly strengthened by many similar allegations. What initially started as two former associates contacting the chief justice of Australia in March last year became public this week after an inquiry she commissioned concluded that “six former Court staff members who were Judges’ Associates were harassed by the former Justice.”

Given this week’s revelations, Heydon’s ruling on Stubley’s appeal is a bit like Weinstein greenlighting a movie about a predatory producer or Cosby doing a very special episode on methaqualones. One possible explanation may, of course, be that Heydon is innocent of the allegations made against him. But there are other possibilities: he may have been somehow oblivious to his own conduct or supremely confident in his invulnerability, or maybe just intellectually devoted to his stance on evidence law. Each of these explanations, in different ways, suggests that Heydon may be his own worst enemy.

Regardless, he was alone on the High Court in 2011. The other four judges who heard Stubley’s case — Bill Gummow (who wrote a classic legal text that Heydon would later contribute to), Susan Crennan, Susan Kiefel and Virginia Bell — all allowed the psychiatrist’s appeal.

Rejecting a different rape appeal five years earlier, Dyson Heydon penned a brief judgement agreeing with the majority, but adding his rejection of the accused’s criticisms of his then trial counsel. “She was dealt very bad cards,” he wrote. “She played them very well. Her methods were the reverse of incompetent.”

Mark Trowell, Alan Stubley’s barrister, was also dealt very bad cards. He told his client’s jurors: “No matter how big a rat he was in having sex with his patients, you can’t just convict him because he was unethical and immoral.” Stubley later testified that sex was considered to be part of psychotherapy in the 1970s. Indeed, his second patient announced that she had researched the field before seeing him and told him that she wasn’t seeking “bed therapy.” Stubley seemingly ignored her request.

Trowell also proved to be the reverse of incompetent. His strategy, while failing at the trial, succeeded in the High Court. Had Stubley denied having sex with his patients — Gummow, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell held — then his jury could have heard the stories of other patients who said they had sex with him. But his admission that he had sex with all of them — consensually, he said — meant that their stories added nothing to the prosecution case. “Proof of the appellant’s tendency to engage in grave professional misconduct by manipulating his younger, vulnerable, female patients into having sexual contact with him,” the four judges wrote, “could not rationally affect the likelihood that JG or CL” — the two patients — “did not consent to sexual contact on any occasion charged in the indictment.”

These judges’ words, in sharp contrast to Heydon’s own, could be music to the ears of any barrister asked to defend the former judge if he is prosecuted for crimes against some of the people whose accounts have emerged this week. If Heydon admits doing the particular acts he is accused of — say, touching a woman’s thighs or hugging or kissing her — but says that the woman consented to those acts, then the majority’s ruling on Stubley’s appeal would bar the prosecution from using others’ accounts of his misconduct, no matter how similar or non-consensual or well-established, to convict him. In short, the majority’s judgement takes the “too” out of #metoo.

I am long on the record as saying that the High Court’s approach to such cases is seriously wrong. Six years previously, the national court had unanimously allowed the appeal of a different alleged predator, a teenager convicted of the rapes or attempted rapes of six different teenagers, by ruling that he should have been tried separately for each. Why? Because he had testified that each of the six consented to sex with him, only to later accuse him of rape. (Remarkably, the sixth instance occurred while he was on bail on charges of raping the other five.) The national court ruled that, as a result, their testimony could not establish any pattern about the accused, but only cast light on their own, separate, decisions not to consent to sex with him.

After that case, I — and others — put much the same legal argument that Heydon put six years later: that six claims of predatory behaviour are much more powerful than one, given the particular unlikelihood of one person facing a series of false claims of rape after consensual sex. Indeed, as Queensland’s director of public prosecutions had argued before the national court, the six complainants’ accounts of the teenager’s actions showed a distinct, escalating pattern of deception before and violence during the alleged rapes, culminating in threatening the last two teenagers with a baseball bat and a chain.

Tragically, two months after the High Court’s judgement was published, the teenager committed two rapes that the judge who sentenced him regarded as “very similar” to the last of the earlier allegations. To no one’s surprise — other than the High Court’s, I suppose — he pleaded guilty to those two rapes, and was convicted of the earlier attempted rape committed while on bail on charges of the five earlier ones.

Heydon was one of the five judges in that earlier case. Because the court issued just one joint judgement from all five judges, and because it hides who actually writes such judgements, we don’t know whether it was authored by Heydon himself, or by one of Murray Gleeson, Bill Gummow, Ken Hayne or Michael Kirby. Regardless, they all signed on to the following remarkable explanation of why the common features of the six complainants’ accounts leant nothing to the prosecution’s case because they were “entirely unremarkable”:

That a male teenager might seek sexual activity with girls about his own age with most of whom he was acquainted, and seek it consensually in the first instance, is not particularly probative. Nor is the appellant’s desire for oral sex, his approaches to the complainants on social occasions and after some of them had ingested alcohol or other drugs, his engineering of opportunities for them to be alone with him, and the different degrees of violence he employed in some instances. His recklessness in persisting with this conduct near other people who might be attracted by vocal protests is also unremarkable and not uncommon.

But Heydon, seemingly alone, had second thoughts. During Stubley’s appeal hearing, he commented that the earlier judgement “is one of the most criticised decisions of the High Court of all time” and “is not a sort of granite mountain that is sharp and immovable.”

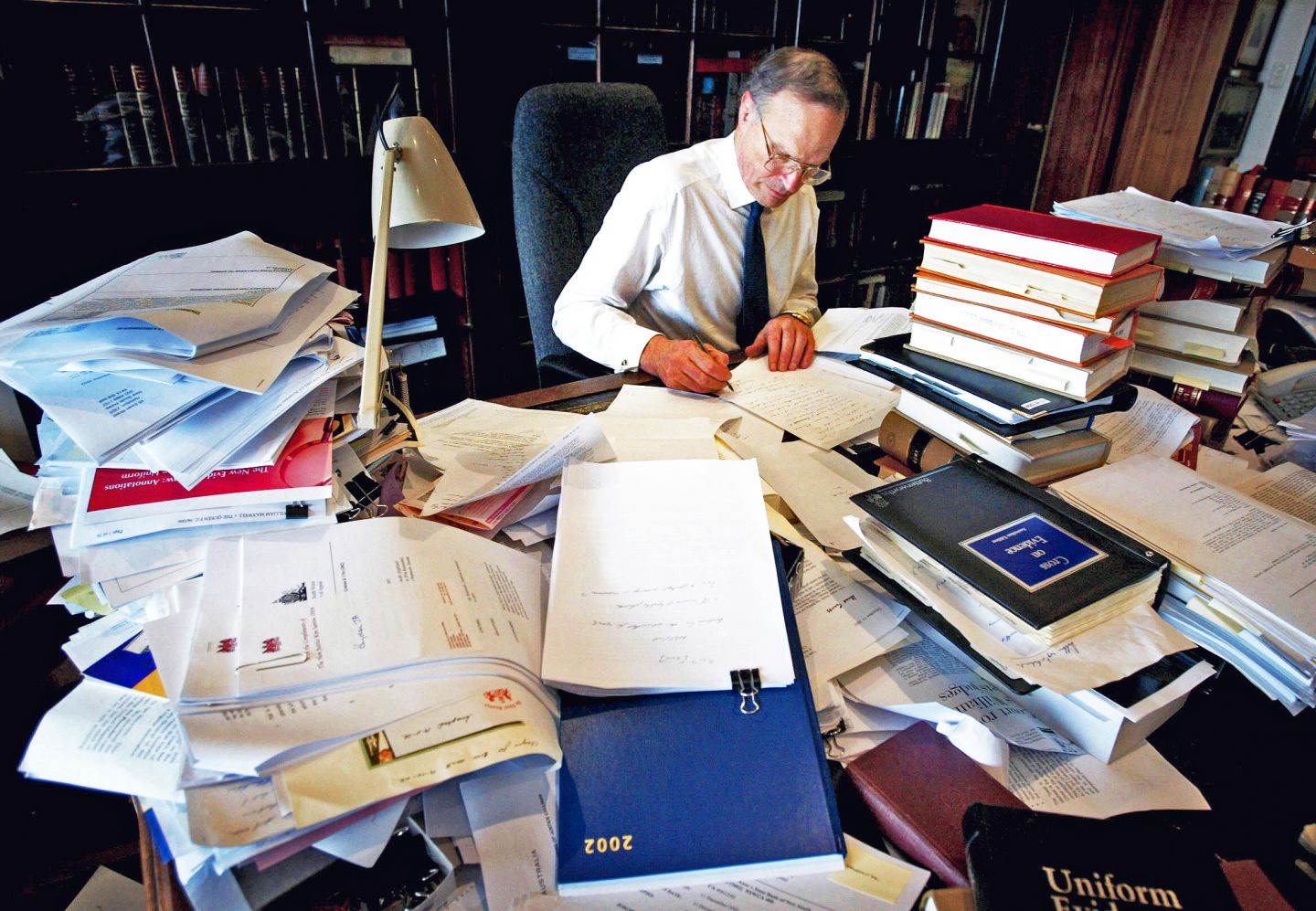

Around the time of Stubley’s appeal, Heydon also changed how he wrote judgements. He started dissenting as often as not and, more dramatically, stopped writing with his fellow judges altogether. In a 2013 interview, he explained that he had belatedly recognised that his colleagues on the bench wrote poorly and that the High Court’s difficult case load merited his individual attention. The previous year, he had given a much-discussed lecture at Oxford criticising the push for joint judgements in senior courts, labelling the pressure towards judicial collegiality — something Chief Justice Susan Kiefel later made her hallmark — “the enemy within.” His post-retirement return to Oxford as a visiting fellow was cut short, the Sydney Morning Herald reports, amid more allegations of predatory conduct, this time with law students.

Alan Stubley’s receptionist, the youngest of his patients to testify at his trial, described how, on her twenty-first birthday, the man she called Dr Stubley — who by then was also her psychiatrist, treating her for anxiety and depression — suddenly approached her and kissed her on the lips, telling her she could now do whatever she wanted. The High Court majority’s summary of her testimony continues:

In a consultation which took place after her twenty-first birthday, Stubley hugged her and undressed her, saying that he knew that she would be beautiful. He had sexual intercourse with her on the floor of the consulting room. She had not wanted to have sexual intercourse with him. During intercourse she had a “frozen grin” on her face. After intercourse he washed himself in the basin. She did not resist because she did not want to jeopardise her employment. She also believed that his conduct was part of his treatment of her as a patient. About a week after this episode she confronted him and told him that there was not to be any further sexual contact between them. Stubley agreed. No further sexual contact took place between the two.

Such terse summaries of the evidence are typical of the High Court and often contrast starkly with the details provided in the judgements of other courts that rule on the same cases. For example, the Western Australian Court of Appeal set out what the now fifty-three-year-old told the jury was behind her then “frozen grin”:

I had a boyfriend, a new relationship, and I had told him about it because it was a patient of his and also I just thought this couldn’t be happening because I didn’t know how to tell him that I felt revolting and he was my boss and I didn’t think I would get another job and he was like a guru or a figure I was greatly intimidated by and basically all of these things were swirling through my mind, just “How do I get out of this? How do I get out of this?”

The High Court’s reasons omit not only such human details, but also the broader narrative. A judgement from Western Australia’s Supreme Court reveals that, when she commenced working as Stubley’s receptionist, aged nineteen, she watched female patients emerge from his office on multiple occasions “looking untidy with crumpled clothes and their hair messed up.” She testified that, when she quit her job six months after confronting her psychiatrist, “she had been dramatically affected by the sexual intercourse to the point she requested admittance to the mental health ward at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital.”

But few people read court judgements. After Stubley’s trial — where, Stubley’s partner told the media, “the gallery was full of patients supporting him” — Justice Narelle Johnson said that she was “staggered” that Stubley’s supporters had written to her saying that there had been “a scandalous miscarriage of justice,” observing that the letters’ authors had seemingly “not heard the evidence.” The partner of one of the two complainants later said that she was left “distraught” by the High Court’s ruling. Lacking legal training, these lay observers would have had difficulty reading the national court’s terse analysis of evidence law. But that would have posed no barrier to a different group, known as judge’s associates, who have a particular interest in the High Court’s handing of professional predators.

Following its initial finding that Dyson Heydon had sexually harassed six judges’ associates, the High Court is now reportedly contacting over one hundred other people who held such roles during Heydon’s tenure on the national court. Visitors to the court’s public hearings can see those associates seated behind each judge, sometimes rising in unison to supply law reports whenever a barrister mentions a precedent. Behind the scenes, they engage in variety of roles including legal research and proofreading the judges’ reasons. The positions — typically two per judge, and lasting for a year or two — are highly prized by future lawyers for the insight they offer into courtroom life and, in many cases, the close interaction with particular judges, which can lead to mentorship or friendship down the track. A new graduate’s selection by a high-profile judge signals a prediction — often self-fulfilling — of a stellar legal career.

We are likely to hear far more about life as an associate in coming days, weeks and months. Chief Justice Susan Kiefel’s statement setting out the current justices’ shame “that this could have happened at the High Court of Australia,” also reveals a number of new workplace safety measures, including clarifying that associates’ obligations of confidentiality “relate only to the work of the court.” Every day of this past week has yielded fresh behind-the-scene revelations, such as the claims that Heydon tried to kiss one of his associates in 2005 and that that information speedily moved through the court to its then chief, Murray Gleeson.

The then associates of Ken Hayne and Virginia Bell would have spent part of the second quarter of 2010 researching Stubley’s trial and initial appeal as a prelude to the two judges granting the ex-psychiatrist “special leave” to appeal his conviction at a brief hearing in the middle of that year. Many of that year’s associates would have travelled with the court’s seven justices to Perth that October to hear a set of Western Australian cases including Stubley’s appeal. Five associates would have been present when — after a two-hour hearing — Bill Gummow announced on the spot that “[a]t least a majority of the Court” had allowed the appeal. And some of those would have spent part of the next six months researching and proofreading the majority’s joint reasons for making that order, as well as Heydon’s lone reasons for dissenting.

They would have read the majority’s declaration that the then law in 1970s Western Australia “recognised that consent to intercourse may be hesitant, reluctant, grudging or tearful but that if the complainant consciously permitted it… the act was not rape.” That none of the three additional patients, including the receptionist, “gave evidence that the appellant had engaged in threatening or intimidating conduct inducing her consent to sexual activity.” That the prosecution’s submission to the contrary “conflates proof of psychological dominance with proof of absence of consent.”

They would have read the majority’s observation about the second patient — who testified that Stubley had once told her that “you seem to be very angry. Sometimes when people are very angry, they need to be put in hospital for a couple of weeks,” and who complained about his conduct to a medical board in 1981, the same year she ceased treatment with him — that “the prosecution did not seek to lead evidence of [her] reasons for not making a prompt complaint.” They would have read the four judges’ conclusion that “the differing accounts of the sexual abuse experienced by” the other three patients “were not capable of bearing rationally on the assessment of” the two rape complainants’ reasons “for continuing to undergo treatment and for not complaining.”

They would have read the joint words of Bill Gummow, Susan Crennan, Susan Kiefel and Virginia Bell that “manipulating a person into sexual intercourse by exploiting that person’s known psychological vulnerability would not, without more, vitiate their consent” and that “the cynical exploitation of [Stubley’s] position of power was not inconsistent with him holding an honest belief that the victims of his attentions were consenting to the conduct.” And they would have read the justices’ conclusion that “absent any feature of the evidence tending to demonstrate [Stubley’s] awareness that his manipulation of his patients had not succeeded in procuring their assent to his predatory advances, proof of the imbalance of power did not rationally bear on the issues raised by” the defence of honest belief.

And, at the same time, Heydon’s then associates would have been proofreading his excoriation of the majority’s reasoning.

In 2007, the High Court dismissed an appeal by a teenager who had been tricked by the two police officers into making what they promised was an off-the-record confession to a home invasion. Murray Gleeson and Dyson Heydon observed that “every day police officers take advantage of the ignorance or stupidity of persons whom they eventually prosecute.” Gleeson, who was chief justice for the first five years of Heydon’s tenure, was allegedly told via another judge and his associate, of Heydon’s harassment of his own associate in 2005. He has largely refused to comment on the High Court’s inquiry into sexual harassment, aside from a cryptic text telling a journalist that “the accounts relayed to you are false.”

Heydon, who declined to be interviewed during the High Court’s inquiry, has stated, via his lawyers, that “any allegation of predatory behaviour or breaches of the law is categorically denied by our client.” He added that, in the case of the associates’ complaints, “if any conduct of his has caused offence, that result was inadvertent and unintended, and he apologises for any offence caused.” As for the other allegations now being detailed in the media, “our client denies emphatically any allegation of sexual harassment or any offence.” The latter is presumably a reference to a crime, rather than an emotion.

What are we to make of such a generalised denial? Ask Heydon. He spent much of his 2011 dissent dissecting Alan Stubley’s combined ethical mea culpa and criminal denial, as delivered by Mark Trowell to the jurors:

Dr Stubley will admit that he was sexually intimate with four of these women… but he says that his sexual intimacy on each occasion was consensual; that is, with the consent of each one of those females, that there was no force or coercion or intimidation or manipulation of any one of those females, and maybe he accepts that he may be morally and ethically wrong for what he did; he’s not guilty of the criminal allegations that have been brought against him and will explain the circumstances in which the sexual intimacy took place.

“A common forensic tactic,” Heydon wrote, “seeks to prevent damning evidence being called, or to water down the evidence which is called, by narrowing the issues in the case.”

Rejecting the majority’s view that Trowell has admitted the various “acts of intimacy” Stubley had been accused of, Heydon pointed out how Trowell “declined to pin his concessions about acts of sexual intimacy to the periods or occasions identified by the complainants.” Indeed, Stubley went on to cast doubt on a number of the specific acts the complainants described, saying that allegations such as sex with a heavily pregnant woman “was not the sort of thing I tend to do” and “not specifically” recalling many specific sexual acts he was charged with. The broad problem, wrote Heydon, is that “it is very difficult to fillet out the details of the relevant events which go only to sexual intercourse from those which are relevant to consent as well.”

There is similarly no way to tell whether Heydon, through his lawyers, is denying that the acts alleged against him happened at all, or is suggesting that they were consensual. In Stubley’s trial, Trowell blamed the passage of time for his client’s refusal to be pinned to specifics:

Can I say this: after thirty to thirty-five years he’s not able to tick a box like a questionnaire to relate to each particular act. I mean, who could? Who could after thirty to thirty-five years? Who could accurately describe in detail things that happened so long ago? Apparently, the complainants can. Let’s see about that.

Heydon thought that “unfortunately phrased”: “perhaps the reason the ‘females’ could accurately describe what happened long ago, while the accused could not, was that the events complained of were unique in their experience, but merely quotidian and banal in his.”

If Trowell winced at that back then, so might Heydon’s lawyers today. But in 2011, Heydon was unsympathetic to the plight of an alleged predator:

It may be thought harsh in the case of offences which allegedly took place as long ago as the offences charged in this case that the desire of an accused to make an admission should be thwarted because he is unable to be specific in consequence of the lapse of time. In some ways it is harsh; in other ways not. The lapse of time brought advantages and disadvantages to the accused. One of the advantages was that it would be easier for the jury to have a reasonable doubt about the evidence of the complainants. One of the disadvantages was that it made it harder for him to make an admission…

He quoted the greatest of modern evidence scholars, Henry Wigmore, who complained that “a colourless admission by the opponent may sometimes have the effect of depriving the party of the legitimate moral force of his evidence; furthermore, a judicial admission may be cleverly made with grudging limitations or evasions or insinuations (especially in criminal cases).” Better, Heydon said, “to let the jury hear the whole unbowdlerised story.”

The High Court’s judgement in Stubley’s case revealed two possible futures to any women at the time contemplating going public with their stories of alleged professional predation. In one future, each woman’s account would be read only for its deviation from their alleged assailant’s mea culpa, and potentially on its own. In the other, decision-makers would see the “whole unbowdlerised story” of the alleged perpetrator’s pattern of behaviour. Those thinking of exposing Heydon’s own alleged harassment and crimes would have found more encouragement in his dissenting words than those of the four justices in the majority, including the current chief justice. The lesson of #metoo is how we can find our enemies in surprising places. Likewise our allies.

Assuming we find them at all. After allowing Stubley’s appeal, the High Court nevertheless ordered his retrial, observing that the psychiatrist faced allegations of “serious offences” and the two complainants’ evidence “was in each case capable of establishing the prosecution case.” Justice Johnson had previously sentenced him to ten years in prison, telling him: “It is unfortunate that no one paid attention to the complaints of these women. You would not have been able to continue your work until retirement.” He had served two years of that sentence when the majority’s judgement freed him.

Two months after their words were published, the eighty-three-year-old suffered a blood clot and underwent surgery. The onset of mild dementia prompted a consultant psychiatrist to find that Stubley would be unable to follow his retrial or the prosecution case, or to defend himself. Western Australia’s Supreme Court ruled that the former psychiatrist was unfit to stand trial and ordered his release into a nursing home, finding that he posed no further danger to the community. As far as I can tell, Alan Stubley died last year, aged ninety. It was not a good end for the retired psychiatrist, but likely better than the one chosen by Dyson Heydon. •