History repeats itself, according to Marx’s famous aphorism, the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. Unfortunately for Australia, there’s a chance that this month’s election in Queensland could reverse the Marxian order of things.

Back in June 1998, Queenslanders elected a hung parliament and came within a whisker of giving the newly formed One Nation a king-making role. Against the odds, the party had received almost 23 per cent of the vote and won eleven seats.

In the end, Labor’s Peter Beattie was able to form government with the support of a dependable independent named Peter Wellington. One Nation, which would soon descend into a fatal bout of infighting, was politically neutered. Led by Beattie, and then by Anna Bligh, Labor went on to govern Queensland for fourteen years.

“Pauline Hanson’s One Nation was a shooting star that blazed spectacularly across Australia’s political skies during 1997 and 1998 before crashing to earth in 1999,” read the introduction to a book called The Rise and Fall of One Nation, and few would have disagreed. Nearly twenty years later, though, Queenslanders have a second chance to give One Nation the balance of power, and they might yet take it.

Neither premier Annastacia Palaszczuk’s Labor nor Tim Nicholls’s Liberal National Party are dominating in the opinion polls, which consistently show One Nation attracting about 18 per cent of voters. This makes the exact make-up of the next Queensland parliament impossible to predict. The number of seats has increased from eighty-nine to ninety-three. Many electoral boundaries have been redrawn. And the state has just reintroduced compulsory preferential voting, which means Queenslanders will once again have to number every box on the ballot.

To add to this confusing picture, Labor is committed to putting One Nation last; One Nation is placing all sitting members second-last, just ahead of the Greens (“with a handful of exceptions”); and the LNP is trying to game the system by preferencing One Nation above Labor in “at least fifty” selected seats. Whenever the major conservative parties preference One Nation, it does well.

“If recently polled primary-voting intentions were replicated on election day, either side could have a big win in the ninety-three-strong chamber,” wrote Inside Story’s Peter Brent at the beginning of the campaign. “But One Nation, registering in the high teens in the polls, is in with a chance for several seats, and that makes a hung parliament less unlikely than hung parliaments usually are.”

Veteran Queensland political commentator Paul Williams went further: “A handful of seats could decide which leader, Palaszczuk or Nicholls, is in a position to form government in what will inevitably be another hung parliament.”

If another hung parliament is inevitable, who will get to be the monarch-maker? Could the Hansonite insurgency achieve in 2017 what it couldn’t do nearly two decades ago? Having dodged a bullet back in 1998, what should Queenslanders expect from a government that must rely on a deal with One Nation? If history is any guide, governance will suffer, but the media will love it.

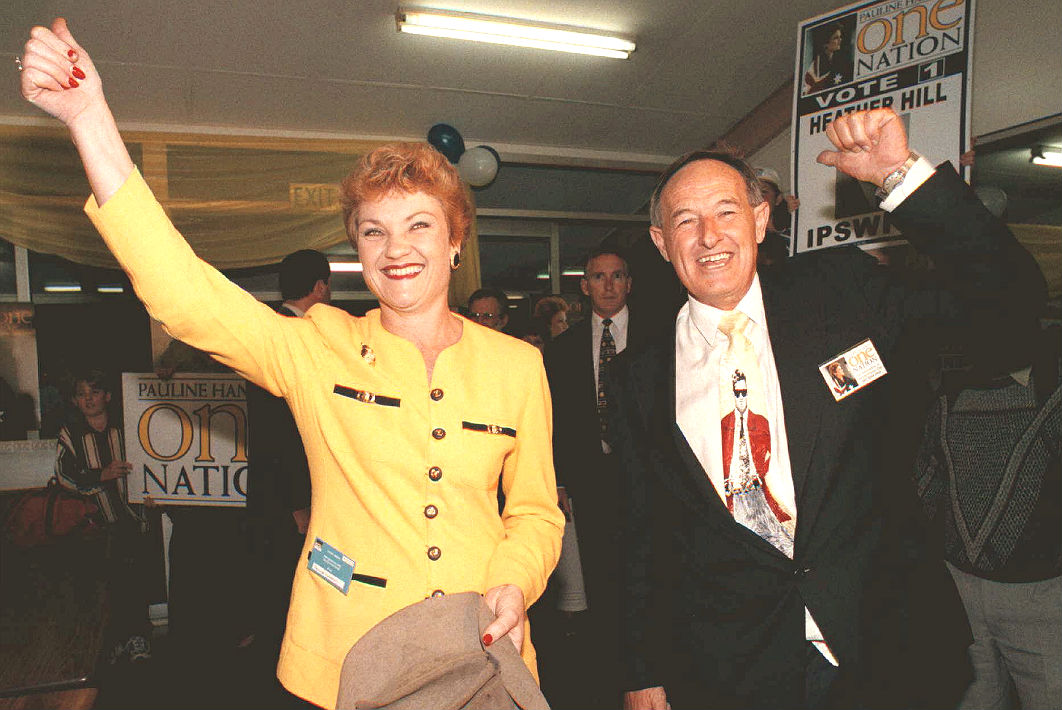

In the wake of her extraordinary victory as an independent in the federal seat of Oxley in 1996, former Liberal Party candidate Pauline Hanson became an overnight media sensation. To capitalise on her new-found fame, she set up her own party. With the aid of her two key advisers, David Ettridge and David Oldfield, she launched One Nation in April 1997.

One Nation was a strange hybrid made up of two separate entities. One was a company called One Nation Ltd, run by the two Davids and Pauline; the other was Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (Membership), and that’s where the ordinary punters resided. Lurking within this undemocratic structure was a ticking time bomb.

By the end of 1997 One Nation had hundreds of branches across the nation and thousands of fee-paying members, but the 1998 Queensland state election result would soon prove to be the zenith of its achievement. At the federal election held just a few months later, One Nation ran an extraordinary 139 candidates — and didn’t win a single seat. Even Hanson herself lost, in the seat of Blair.

There was some consolation in the fact that a friend of Hanson’s from Ipswich called Heather Hill was elected to the Senate. But within a month Hill’s victory was challenged by the National Party’s Bill O’Chee, who argued she was a dual citizen of Australia and Britain. In June 1999, the High Court found her election was invalid. She was replaced by One Nation’s number-two candidate, self-employed goldminer Len Harris.

Things were not going well back in Queensland either. One Nation’s leader in the Queensland parliament was a former cop called Bill Feldman, who had taken the seat of Caboolture from the National Party. His ten colleagues were equally inexperienced in politics, but not so inexperienced that they failed to notice that things were crook in Tallarook.

In early 1999, Hanson and the two Davids had tried to force a change to the party’s constitution that would enshrine their own power. Half of One Nation’s Queensland MPs promptly quit the party and sat in parliament as independents. Later in the same year, further disputes with the remaining rump of MPs about the copyright of the One Nation name led Hanson to sack the lot of them. Dubbed “white ants” by the Hansonites, they set up a new party called the City Country Alliance.

One Nation degenerated into a publicly funded political soap opera. In 2003, after a lengthy legal process, both Pauline Hanson and David Ettridge were found guilty of electoral fraud by the District Court of Queensland and sentenced to three years’ jail. They each spent eleven weeks in prison before the verdict was quashed by the Queensland Court of Appeal.

Dual-citizenship senators, Svengali advisers, arguments between Pauline Hanson and her lieutenants, resignations from the party — it all sounds so wonderfully familiar.

Earlier this year, following the errant example of Heather Hill, One Nation senator Malcolm Roberts was bumped when the High Court decided he too was a dual citizen. His replacement in the Senate, Fraser Anning, waited until he was sworn in then resigned from the party. He currently sits in the Senate as an independent but is strongly tipped to join either the Liberal Democrats or the Australian Conservatives. Anning blamed Hanson’s chief of staff, James Ashby, for his decision to flee One Nation. The ghosts of the two Davids still haunt the party, it seems.

One Nation’s traditional peculiarities have once again been on display during campaigning in Queensland. The party’s candidate in the north Queensland seat of Thuringowa was exposed by the media as a sex-shop owner who promotes his business on Facebook in a way that trivialises domestic violence. The party’s Queensland leader, former LNP member Steve Dickson, thinks the safe schools program teaches students “how to masturbate, how to strap on dildos.” Malcom Roberts, now the party’s candidate in Ipswich, has been attending fathers’ rights rallies in the electorate. More seriously, his former campaign manager, Sean Black, has been charged with sexual assault.

And what if One Nation does grab the balance of power in Queensland? Expect the traditional trench warfare between a Canberra-based Pauline Hanson, aided and abetted by her chief of staff, and a small team of inexperienced Queensland MPs huddled together in Brisbane. Since its birth in 1997 there have been twenty-six One Nation MPs elected in state or federal politics. Of those, sixteen have either quit or been expelled from the party.

The Pauline Hanson brand seems to be indestructible. Despite running for office and often failing, despite leaving a conga-line of embittered former allies behind her, and despite losing on Dancing with the Stars, Australia’s favourite right-wing populist just keeps on keeping on.

And we can probably expect history to keep on repeating as well. ●