As we walk through the world, each of us sees differently. That’s been a truism about art since John Berger first remarked on it, yet we still regard filmmakers as people who direct actors and crew. Really, what a great filmmaker does is direct our gaze.

Viva Varda, the monumental Kristy Matheson–curated retrospective of the films of French director Agnès Varda — taking in ten of her features and four of her shorts — shows what an exceptional filmmaker she was, and what a singular gaze she turned on the world. After running through the Sydney Film festival, it’s playing in Melbourne until 30 June and then moving to Canberra.

Varda died, aged ninety, on 29 March this year. In the fourth phase of her career, a last late flowering following the triumph of her 2000 digital documentary The Gleaners and I, she put more of herself on camera and we began to know more about her. That she was tiny — less than five foot tall. That she still wore her hair in a kind of punk pageboy bob, like a medieval monk. That she was energetic, vehement in her opinions and partial to puns and had a wild sense of humour.

Who else would turn up at the opening of one of her installations at the Venice Biennale dressed as a potato? Or, receiving an honorary Gold Leopard at the Locarno Film festival, announce, “Well I have a Lion from Venice, and a Bear from Berlin. Now I can say I am a Leopard,” before producing a leopard-skin lycra onesie from her handbag. Somehow, I can’t see Jean-Luc Godard doing that.

Varda was an accomplished professional photographer when, in 1954, aged twenty-six, she wrote and made her first film. Had she known more about cinema she might not have attempted it. But she was interested in the moderns of literature — writers like Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner — and wanted to make a cinema of impressions and emotions, very different from standard narratives.

Like Faulkner’s novel The Wild Palms, that first film, La Pointe Courte, swings between two parallel stories: that of a couple from Paris, reassessing their relationship now the first passion has passed, and that of the men and women of this small fishing village. Varda cast real villagers and made drama of several struggles: a daughter wanting to walk out with her boyfriend, fishermen battling a bureaucracy that would stop their livelihoods, a pregnant woman, a group of women clustering around one dealing with the death of a child.

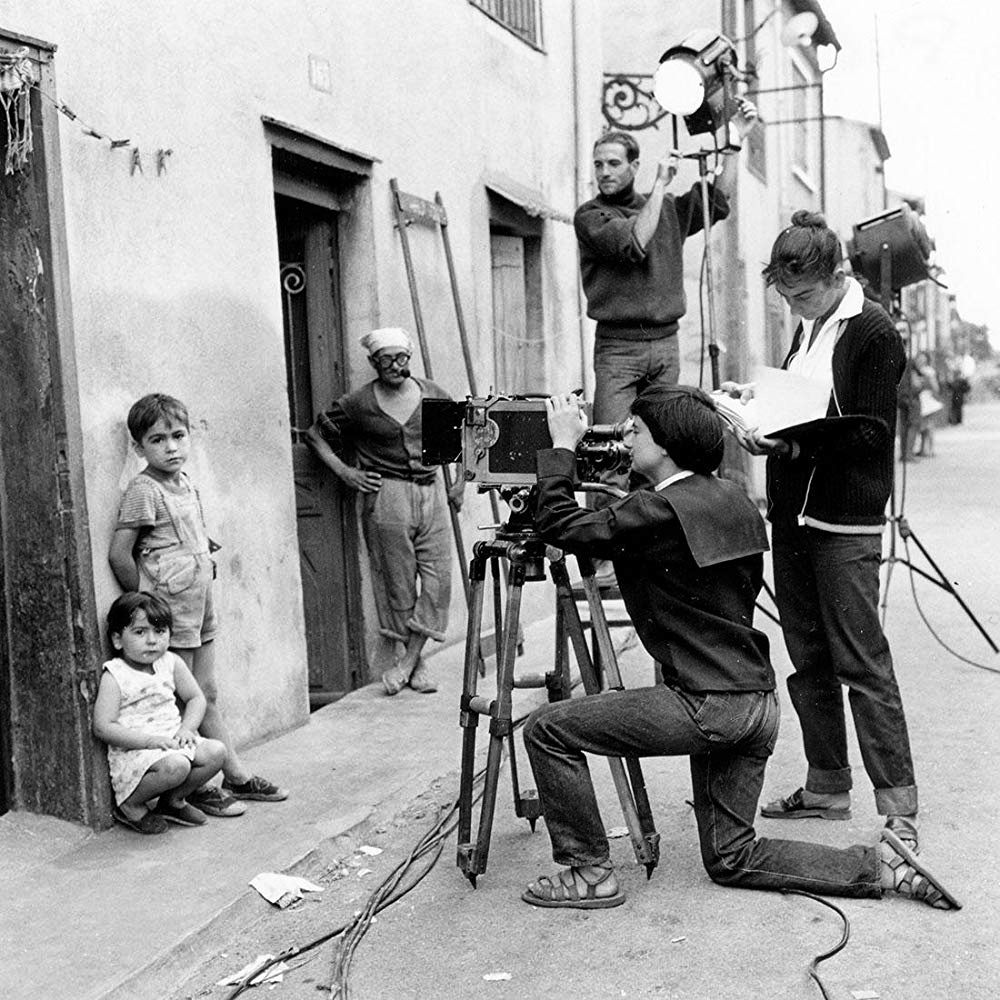

It’s also an extraordinarily tactile film. As her camera explores the surfaces around the two lovers, you want to reach out and stroke the celluloid. She brings the villagers to life with great verve, and her observations include the kind of drama — a child’s death, a pregnancy — that prefigures a lifetime empathy for the experiences of women. “I should have ‘Don’t Touch’ written on here!” wisecracks one of the village women, patting her pregnant belly.

Tactile: Agnès Varda shooting her debut feature, La Pointe Courte, in 1954.

La Pointe Courte was made four or five years before the first films of the French New Wave. And though Varda would collaborate with the Cahiers du Cinéma mob — she cast Jean-Luc Godard, for example, in a small film-within-a-film in her second feature, Cléo from 5 to 7 — she pursued an independent path. From 1977 on she ran her own company and was her own producer. In this, as in so many things, she was a pioneer.

From the outset Varda brought to her cinema her own experiences as a woman and equally an intense curiosity about others. She knew what it was to be a stranger, to be exiled, and to be on the edges of power. She knew celebrity, but equally she knew the people on the street where she lived, and she investigated both in her films.

In one way, it’s possible to look at Varda’s work and see her scrutinising most of the experiences women have over their lifetimes, from teenage passion to widowhood. Equally, she shows us a neighbourhood. And sometimes, without sentimentality, a community.

Diary of a Pregnant Woman (1958) begins with the filmmaker pointing the camera at her own pregnant belly and then exploring the people she sees in the street market of Rue Mouffetard. This is Varda, about to bring a child into the world, looking at those around her as she wonders what her unborn child’s life will be like. It’s a woman in the grip of the heightened emotions of pregnancy, scrutinising the faces of those whom life has treated harshly. The faces her camera scrutinises are not mere backdrop.

In the second phase of her career, when she followed her husband Jacques Demy to Hollywood, her political sympathies produced some significant documentaries: on the Cuban revolution (Salut les Cubains, 1964) and on the Black Panthers (1968), prompted by the trial of Huey Newton. While keeping a toehold in France, she used her camera to nose her way into her new world in California. Lions Love (… and Lies), the 1969 American feature film in which she persuaded the Warhol star Viva and the creators of Hair to take part, is a wacky exploration of the American cult of celebrity, counterposed with politics, that slips in and out of control.

Mur Murs (1981) — on the Latinos of Los Angeles, and the murals that marked their presence — is in this retrospective, too. So is Documenteur (1980), which despite its name is a fiction, if a thinly disguised one. One of the most nakedly painful of Varda’s films, it was made after she and Demy separated in Los Angeles, and tells the story of a woman with an eight-year-old son trying to find somewhere to live and dealing with the pain of separation. Mathieu Demy, aged eight, plays the son, and as the woman Varda cast Sabine Mamou, who was her editor on Mur Murs.

It is a raw and affecting film in which a series of inner monologues reveals Varda as a skilful writer in English, alert to rhythm and repetition. It also shows a side of Los Angeles far from the luxury of the Hollywood Hills: a beachside scene of crumbling apartments and concrete walkways, of casual kindness and occasional brutality. For all her concerns about the inner lives of her characters, Varda never uses the places and people around them simply as metaphors. Her gaze is turned on others with a mixture of curiosity and compassion.

The feminism of Varda’s earlier films was not always accepted by audiences. Cléo from 5 to 7 got a Venice premiere and was acceptable enough because it starred a beautiful young singer (played by Corinne Marchand) who walks the streets of Paris while she waits for news of a cancer diagnosis. Emotionally, it was about a woman rejecting the way others looked at her.

But Varda’s third feature, and her first venture into colour, Le Bonheur (1965), with its arresting code of rich, Renoirish tones to signify emotions, was widely misunderstood. Essentially, she was using irony to question the love–marriage–family–happiness cliché offered to women, embodied in the film by an uxorious husband, a blonde wife and two contented children. After the man meets an equally desirable blonde woman and she becomes his mistress, the wife obligingly suicides and the mistress takes her place. It’s fair to say most mainstream critics didn’t get it, and the outriders of the re-emergent women’s movement didn’t either. Some feminists, back then, had a lot of trouble distinguishing between description and prescription. Some audiences still do.

Varda was dividing her time between France, where she knew the film scene and had the necessary contacts, and California. She was also becoming more involved with the women’s liberation movement. She read the texts — Kate Millett, Shulamith Firestone, Germaine Greer — and made a short film, Women Reply (1975), responding to the Bobigny affair, the outrageous jailing of a mother who procured an abortion for her raped fourteen-year-old daughter. Two years later came One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977), a feature-length drama about two female friends from different class backgrounds, drawn together at different times while they consider whether they will have children or terminate pregnancies. It had the temerity to be a musical.

Across the divide: Thérèse Liotard and Valérie Mairesse in One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977).

There comes a time, for many who have worked for any length of time in cultural production, when they notice the waters of collective memory closing over them. There is a canon, and it is constructed and policed by middle-aged white men. The concerns of women don’t much interest them.

It happened to Varda in 1980, when Cahiers du Cinéma published special editions on French cinema two years running and omitted her entirely. The “mother of the new wave” had by this time been making films for more than a quarter of a century. She was deeply hurt, and said so in an interview in the rival journal Positif.

“I wasn’t mentioned even in passing,” she said, “not a single one of my films. God knows there were a lot of people mentioned, and very interesting people, different people, French filmmakers of all stripes, men, women, people from the Auvergne. But not me. Was it because I was in the US? Louis Malle was also over there. Was it misogyny? Surely not. Catherine Breillat, Marguerite Duras, and others were included. Was it the omission of anyone less than five feet tall? No, Chantal Akerman was in there. I was just plain forgotten.”

Varda learned the lesson, and in later years she would produce and direct her own cinematic autobiographies: The Beaches of Agnès (2010) and her last film, which premiered this February in Berlin, Varda by Agnès (2019).

But she had come back to critical attention well before that with one of her greatest films: Vagabond (1985), a riveting feature film about a young woman who has walked out of an office job and taken to the roads of rural France. At the centre is an astonishing performance by Sandrine Bonnaire, just seventeen when she was cast as Mona. Varda’s tracking shots of Mona with rucksack and tent striding along roads, across fields and through the farms and villages of wintertime Provence give the film a restless forward motion, the camera often racing ahead of a young woman who values freedom from authority above all else.

We meet an astonishing array of outcasts — they could be ours today — and those who prey on them. A gang of drunken youths. A dealer who wants to pimp her. Scam artists, thieves, squatters, labourers from Tunisia warehoused to work rural farms. There’s kindness as well as ruthlessness in these encounters. But there is always a catch, even if it is only satisfying the curiosity of the middle-class woman who picks her up when she is hitching a ride. The bourgeoisie do not come out well in these encounters.

Varda frames Mona’s journey with interviews, often voice to camera, with people Mona has met along the way. They each see her differently: for one rural housewife, she represents the escape from a prison of marriage; another, exploited by her layabout lover, envies the tenderness she thinks Mona obtains from a squatter boyfriend.

Vagabond is not an easy watch. Rarely does a film make so explicit the intersection of class and patriarchy. American road movies like Easy Rider seem laughably romantic and thin by comparison. By forsaking a single narrative stream, it is much more complex and insightful than later, lauded “outcast” films such as the Dardenne Brothers’ 1999 Rosetta, winner of the Palme D’Or at Cannes.

Thirty years on, as homelessness increases, the brutalised corpses of women are found on the streets, the best that policy-makers can offer are education campaigns to combat male violence, and political leaders make an economic virtue of ignoring the jobless and the homeless, Vagabond is still a film absolutely for our times.

Viva Varda doesn’t deal with the third phase of her career, in the late eighties, when she nursed her husband Jacques Demy through a final illness and made first one, then a second film about his life and work. But the retrospective does include films that celebrate friendship — and fun, such as Jane B. for Agnès V., which uses clips of her friend Jane Birkin’s work to celebrate her career. She was “sampling” long before it became a thing.

The retrospective lets us see that the concern for social outcasts that dazzled new generations of film goers in her digital essay film The Gleaners and I was always there. She pointed us to the excesses of consumption of waste. That film is a great companion piece to Vagabond, pointedly critiquing the material waste and exploitation of consumption through the eyes of those who scrounge for its scraps. It’s also an essay on the way artists scrounge and recycle ideas, on her own ageing, and on our own attitudes to the old. It has enormous wit and warmth, and it opened new doors for Varda as an installation artist and photographer. She gleefully recycled some of her own “failed” works, such as the glowing gold film strips of Le Bonheur, to create a temporary dwelling. A home of cinema, if you like.

Viva Varda, first shown at Melbourne’s ACMI in 2014, is the most extensive retrospective attempted of Varda’s work. It’s timing was not accidental: there was still hope then that Varda would live long enough to once more jump on a plane. On view again in Melbourne, it celebrates the restored glory of Melbourne’s Capitol Theatre, just open. Wherever it shows, it’s worth a visit to see Varda’s wit and prescience. It’s time now to seize the cinema canon and shake it. Varda’s films will keep on giving. •