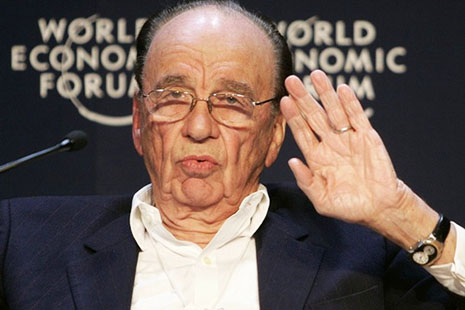

JUST when it looks like things can’t get any worse for News Corporation, another scandal is engulfing Rupert Murdoch’s $50 billion media empire. This time the Murdoch pay TV businesses are under scrutiny. Allegations aired last week on the BBC and published in the Australian Financial Review suggest that News Corp’s former subsidiary NDS, which is now being sold to Cisco for $5 billion, ran an extraordinarily dirty campaign to undermine its rivals. News denies any suggestion of wrongdoing.

NDS is not a broadcaster, but it occupies a critical, and very lucrative, place in News’s global pay TV business. In competition with a small number of other providers, NDS sells the conditional access systems used to ensure that only subscribers can view pay TV channels. In this game, the integrity of the system is everything: the pay TV business model depends completely on restricting access to the signal to paying customers. If a conditional access system is hacked, unlocking keys can be posted online, and counterfeit cards can easily be manufactured and sold, with potentially drastic losses to the broadcasters involved.

On the basis of emails obtained by the Financial Review, it is now claimed that NDS may have used hackers to facilitate the widespread distribution of keys and counterfeit cards for use on competitors’ systems. The alleged aim was to cripple News Corp’s rivals in the pay TV and conditional access industries, thus boosting the market value of NDS and other News Corp businesses.

The leaked emails are posted on the AFR’s website. They paint a disturbing picture, suggesting that NDS set up “honeypot” websites to trick signal pirates into revealing their secrets; put friendly hackers on the payroll and threw others to the wolves; used a shadowy division called Operational Security, run by former British cops and Israeli spies, to conduct surveillance; and paid an army of lawyers to keep a lid on the whole affair.

Phone-hacking victims and critics of News Corporation may well feel as though their worst suspicions have been realised. News, and some of the related companies concerned, have denied the allegations. The risk for the company is that these claims, if substantive, will open News to regulatory inquiries, and civil and criminal litigation around the world. If it were shown that the actions of the group at the centre of the NDS story were authorised corporate strategy, it would remove any doubt as to whether the problems at News are down to a few rogue staffers or are the result of a wider malaise.

But there are other lessons to be learned here. News Corp is clearly not the only media company to engage in this kind of skulduggery. Nor will it be the last. Many of the new revelations, while deeply unpleasant, are unsurprising given the amounts of money at stake. Although there can be no justification for the actions described in the emails, it’s useful to take a wider view of the NDS affair.

The events of this week suggest that some of our conventional ways of thinking about the media and piracy are remote from the realities of the business. Seen in relation to the strategies deployed by some of its competitors, News Corp’s alleged hiring of hackers is not unusual. Most companies in information technology industries will reverse-engineer their competitors’ products, taking the code apart to find innovations and vulnerabilities. Hackers are regularly recruited for such tasks. According to the AFR story, some individuals associated with NDS went a step further, using their knowledge to develop and distribute software that could cripple their competitors’ businesses. But even this case reflects a wider pattern of connections between corporations, spies and pirates that has shaped, and continues to shape, media industries.

There are many examples of the intermingling of white, grey and black media business practices. Book publishing in the United States, now the centre of a global industry, developed successfully in the nineteenth century largely outside the international framework of copyright law. The US cable television industry began its life redistributing the signals of free-to-air broadcasters. Entrepreneurs prospered by picking out neighbourhoods where over-the-air signals were poor. They installed basic cabling, and energetically signed up TV-deprived residents for low monthly payments. But they had no permission from the broadcasters to use their signals in this way, and so, from the point of view of the big networks, this was piracy.

Over time, cable matured into a more formal system underwritten by industry agreements, law and regulation. But we should not forget that its roots in the United States are in unlicensed retransmission. The allegation that News Corp used cable pirates for its own purposes suggests a healthy respect for tradition in an industry better known for rapid change.

One of the many other examples of the interdependence of piracy and media companies was revealed in a recent lawsuit launched by Viacom, parent company of Paramount, MTV and Comedy Central, against Google’s YouTube. Viacom claimed that YouTube was profiting from illegal uploads of programs like South Park and The Daily Show, and asked the court for compensation. The judge decided in favour of Google. During the hearings it emerged that senior Viacom staff, while publicly criticising the “pirate” business model of YouTube, had secretly been uploading clips to the site for marketing purposes. They had even engaged marketing companies – eighteen of them – to “rough up” the clips so they looked like fan uploads. While one arm of Viacom was declaring war on pirates, another was teaming up with them.

The anti-piracy script – the familiar story used to support ever-tougher intellectual property protection around the world – describes a Manichean battle between hard-working creatives and enterprising thieves. Today’s media landscape is much more complicated, with corporations engaging not only antagonistically but also strategically with the world of hackers and pirates. When it’s convenient, mainstream media has a remarkable potential to adapt and adopt the tactics of its enemies. And when the price is right, renegade hackers also cross over into the corporate world.

What all this suggests is that there are few clear boundaries between right and wrong in the media business, just lines of temporary demarcation. Although it may be tempting for some to think of News Corp as the bad apple in the basket, this would be a comfortable illusion. News Corp’s day of judgement – however it transpires – will be but one act in a larger game.

Meanwhile, we could reconsider some of our assumptions about this area of the business world. What the NDS affair suggests is that piracy is not something confined to the periphery of the cash economy, or to under-regulated emerging economies. It can also be found at the very heart of the mainstream, as another weapon in the arsenal of commercial media enterprise.

Is it time to change our image of the typical pirate? •