Museums are contested spaces. Like all forms of history-telling, they are involved in a complex process of assemblage and construction. Whatever a museum’s purpose might be, it can’t avoid the exercise of power: it inevitably sanctions some stories while silencing others.

The Australian War Memorial has wrestled with this dilemma for decades. A towering influence in the political and public domain, the institution’s conservative roots have placed it at the forefront of heated debates about the country’s past. Perhaps the most controversial debate has revolved around the AWM’s refusal to formally recognise the frontier wars (1788–1930s) as part of Australia’s military history by way of a permanent gallery – or, as one historian has suggested, an entire wing. Even as the orthodox foundation story of European progress and peaceful settlement has been undermined elsewhere, the AWM has resisted pressure to formally recognise a violent narrative of invasion and dispossession.

Only now are there signs that times are changing. Over the past six months, two actions by the AWM have suggested a shift in its interpretation – the opening of the exhibition For Country, for Nation and the unveiling of Ruby Plains Massacre 1 by Rover Thomas. For Country, for Nation, which has barely been given a sideways glance by historians outside the AWM, could well be the first, long-awaited response to the academic and public critique that has persisted against the institution for decades. Certainly, the display of Ruby Plains Massacre 1, a 1985 artwork that tells the story of the killing of several Aboriginal men who were found butchering a cow at a cattle station in the Kimberley, represents a conscious and public gesture by the AWM’s council and its director, former federal minister Brendan Nelson, to acknowledge a far deeper narrative than the one they have previously committed to telling.

For Country, for Nation opened in the AWM’s Special Exhibitions Gallery in September last year. Designed to “commemorate Indigenous service men and women,” its inclusion of more than sixty works of art from thirty-two artists reflects some of the most extensive consultation undertaken by the institution in recent times. Indeed, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders and knowledge-holders played a central role in the creation of the exhibition.

For Country, for Nation tells an unfamiliar narrative, both in style and format. Abandoning the chronicling so often treasured in the AWM’s permanent galleries, the exhibition is structured around a series of thematic spaces. As the rhythmic drumming of the Wiradjuri Wagana echoes through the three corridors, visitor movements through the space take an entirely new and refreshing form, emphasising a freedom (rather than order) of movement. Indeed, the six themes – “We Remember,” “The Warriors’ Strength/The Diplomats’ Patience,” “All Heroes/Our Stories,” “Communities on the Front Line,” “Human Rights and Social Justice,” and “Our Cultures Continue” – reflect the curators’ efforts to resist a single dominant narrative. This is by no means an easy accomplishment in the context of Australia’s continuing obsession with Anzac.

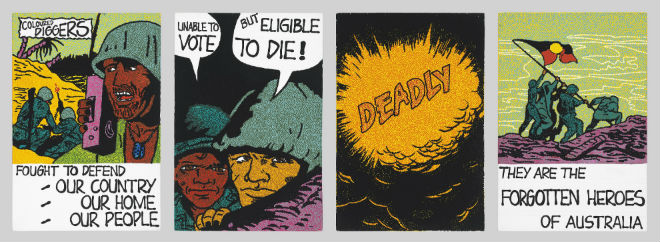

Tony Albert, Coloured Diggers, 2013. Australian War Memorial, ART96531

In telling a history of Indigenous service, the curators have also been careful to respond to other critiques of the AWM’s permanent galleries. Men and women stand alongside each other in For Country, for Nation: the legacy of Reg Saunders, the first-known Aboriginal soldier to rise to the rank of captain, accompanies that of Marjorie Anne Tripp, the first-known Aboriginal woman to join the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service. And the stories of the battlefront are balanced with those of the home front: the exhibition covers figures like human rights activist Margaret Lilardia Tucker, who was forcibly removed from her parents under the assimilation policies of the twentieth century but subsequently dedicated much of her life to the home-front war effort during the second world war.

While there is much to be admired in For Country, for Nation, some visitors will find it bittersweet. Not only is the first exhibition at the AWM to honour Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander military service temporary, but it once again adheres to a decades-old idea that Australia’s most eminent military museum (as well as shrine and archive) is not the right place to tell the story of the nation’s first and longest war.

Some elements of For Nation, for Country do resurrect past and continuing concerns surrounding the Anzac legend and an aggressive, militarised Australian nationalism. For example, army reservist Gareth O’Connell sees continuity between the frontier wars and the role of Indigenous soldiers in Australia’s overseas wars: “Anzac is a modern incarnation of that spirit in defending our country.” Though O’Connell speaks as an Aboriginal man, not everyone would agree that the Anzac legend – the exclusive national myth that still underpins the AWM’s resistance to formally recognise the frontier wars – is an honourable extension of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ military history.

Shirley Macnamara, Memoir, 2015, Australian War Memorial, ART96854

But there is more to For Country, for Nation than might first meet the eye. The exhibition is saturated with comments and images that hint at curators’ disillusionment at, and perhaps even resistance to, the conservative interpretation that has previously defined the AWM’s galleries. Indeed, the exhibition clearly recognises a far darker past. Overt references to the frontier wars appear several times. Shirley Macnamara’s beautifully woven spinifex crucifix, Memoir, “reminds us of the battles fought at home” as well as in “a distant land.” Brodie McIntyre’s didgeridoo honours “his ancestors, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have died and haven’t been so far.” Beautifully decorated boomerangs, shields and spears adorn the eastern corridor, and a declaration by Reg Saunders is inscribed on the wall:

I don’t owe any allegiance or loyalty to the Queen of England; they tried to bloody destroy me, and my family, my tribe, my people… We were the first defenders of Australia – the English never ever defended Australia at all; we did and we suffered very badly for that – decimated to hell.

Then there is the recent permanent installation of Ruby Plains Massacre 1 by Rover Thomas, which is prudently positioned on the western side of the hallway immediately outside the gallery. As journalist Karen Hardy commented, “The first thought is to ask why such a painting even has a place in the Australian War Memorial.” The painting, as Hardy rightly points out, directly contradicts director Brendan Nelson’s claim that the institution is not the right place to tell the story of the frontier wars.

Even if the display of Ruby Plains Massacre 1is intended as nothing more than an effort to give context to For Country, for Nation, its unveiling is important. In its acquisitions, the AWM has often been forward-looking, and Thomas’s painting is certainly not the only piece of this type in its collection. Curators and acquisition staff have been giving careful attention to items and artefacts associated with the frontier wars for years.

Perhaps the defining difference between the unveiling of Thomas’s painting and For Country, for Nation lies in who curated them. Where the inclusion of the painting might have been intended as a conscious and public gesture by the AWM, For Country, for Nation is part of a centuries-old struggle by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to maintain, even reclaim, agency over their own story. For those who look carefully, it will be the words of Aboriginal man Gabriel Nodea, inscribed on the western wall of the gallery, that will carry the potential to redefine the exhibition: “The most important thing I would like to make clear to the rest of the world is our art centre is our last line of defence.” For an exhibition driven by art, this is no idle inclusion; it refers directly to the continuing struggle experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples against the legacies of colonisation. For Country, for Nation is part of that struggle.

As I sat on the small white platform beneath the screening of the Wiradjuri Wagana by Kaa Kaa Wakakirri, two young children in a nearby gallery slipped away from their father’s side and came to crouch beside me. Only a moment passed before they became captivated by the dancers on the wall before us. When the screening finished, the children settled down for a second look. We were only halfway through when their father found us, ready to direct his children back to the gallery they had wandered away from. But like his children, he too stopped to watch the dancers. Moments later, he turned to wander the corridors of For Country, for Nation. When I left the exhibition a few minutes later, the children were still sitting and watching the dancers twirl.

It would be easy to dismiss For Country, for Nation, and the unveiling of Ruby Plains Massacre 1 as empty gestures by the AWM. But that would be a narrow reading of the two actions. Though they might not represent a shift in the AWM’s official remit, they do reflect a willingness to acknowledge the very first war fought “for country, for nation.” •

Our thanks to the AWM and the artists for agreeing to let us publish reproductions of Coloured Diggers and Memoir.