Between 1922 and 1924 the world of ice was chemically fixed onto celluloid and projected onto the world’s silver screens. The cryosphere flickered into life as a hybrid scientific and cultural object, with three films and one scientific text combining to imagine and portray glaciers, ice and snows from the polar regions and the “third pole” — the Himalaya — as a single earth system.

On 9 December, we reach the centenary of the final of these four works. In 1924, the first serious attempt to reach the peak of Chomolungma (Mt Everest) had ended in tragedy, as the British mountaineer-explorers George Mallory and Sandy Irvine met their deaths near the summit on 8 or 9 June; whether they reached their prize has remained a mystery. Their fatal quest was immortalised in The Epic of Everest, the film made by the expedition’s photographer John Noel that opened in London on 9 December, barely six months from their deaths atop the great mountain. The eighty-seven-minute film’s premiere season was accompanied by a live performance by seven lamas brought from Tibet to perform their traditional music and rituals.

Noel’s Epic was a cinematographic summit of a kind, for two other films had illuminated the world of ice on the big screen in the preceding two and a half years. Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, featuring the happy Inuit hunter and his family in the Arctic, had premiered on 11 June 1922 in New York. Herbert Ponting’s Great White Silence, his feature film using moving and still images from Robert Scott’s tragic expedition to the South Pole between 1910 and 1912, had premiered on 5 May 1924. By the end of 1924, the icy realms of the Arctic, Antarctic and Himalaya had been cinematically captured.

By wonderful coincidence, a significant scientific text emerged at the same time, barely registering in either scientific or popular spheres, but influential since. In 1923 a Polish scientist, Antoni Dobrowolski, published a 940-page work in his native language titled Natural History of Ice. In it he coined a term in widespread scientific use today: cryosphere. His definition was a bit wider than generally now used, but he wanted scientists and others to recognise the frozen elements of Earth as an interconnected and distinct object of study. Glaciers and ice sheets, snow, permafrost, sea ice and ice in rivers and lakes form the cryosphere.

Born in 1872, Dobrowolski became a Polish nationalist as a young man, which led first to prison and then to exile in Switzerland and Belgium. While a student at the University of Liège he had the great luck of being appointed to the scientific staff of the Belgian Antarctic Expedition. It set sail in 1897 under Adrien de Gerlache, and included men who would go on to greater polar fame: the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who would be the first man at the South Pole in 1911, and the American Frederick Cook, who would make a fiercely disputed claim to reaching the North Pole in 1908.

Aboard their ship Belgica, the expedition was the first to spend winter in Antarctica (although an exceptionally unhappy one). Dobrowolski helped to collect the first full year’s worth of meteorological data on that continent. After returning to Europe, he spent time studying snow cover and snow crystallography in Sweden, and then continued his geoscience career in Poland.

Dobrowolski’s “cryosphere” concept languished for decades after its 1923 birth. Snow and glaciers were generally studied by different groups of scientists, with meteorologists looking to the atmosphere and its snow while glaciologists looked to glaciers and ice. The term really came into greater use from the 1980s. By this time, the sense of a unified and earth-spanning ice system had intensified, owing a great deal to the emergence of remote sensing through satellites; sea ice, for example, began to be continually monitored with satellites from 1978. The cryosphere was also increasingly a subject of global environmental concern and governance. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change included the cryosphere in its earliest assessment work in the late 1980s and early 1990s and published a special report in 2019.

Yet the cryosphere is more than a physical system: it is a cultural matter too. People have always lived with glaciers, sea ice, snow and permafrost, but until the twentieth century that experience and its meanings were relatively localised. With the advent of Antarctic and Himalayan exploration in the early twentieth century, along with the rise of cinema, the cryosphere as a potentially unified global entity could begin to coalesce and be filled with meaning.

The three cryosphere films — Nanook, Great White Silence and Epic of Everest — are famed and remembered for the people at their heart. But in linking them as cryospheric films in this era of climate change, I think it’s worthwhile and indeed enjoyable to look beyond, behind and around the men to the icy worlds they inhabited and traversed. We can view them as an unintentional and coincidental suite.

Try as we might to view them anew and through the concerns of the present, though, they were nevertheless made in a world with particular human attachments. They are undoubtedly products of a high imperial moment, whether in their valorisation of the great British male explorer or in their patronising approach to Indigenous and local peoples. Today, despite our increasing sense of glaciers’ and ice sheets’ fragility and sensitivity to global heating, they remain fields for physical exertion and personal valour and achievement.

Let’s begin with Great White Silence, which had a longer performance history than its May 1924 release date might suggest. The film tells the story of Robert Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition, which aimed to reach the South Pole. While Scott was bested in that aim by Roald Amundsen, he guaranteed his immortality by dying on his return with the other members of his party.

Expeditions of the age were media events, and so Scott brought along as official photographer the “camera artist” Herbert Ponting (1870–1935). Ponting’s exquisitely composed photographs and eye for action have come to define the visual record of this era of Antarctic exploration. The quality of Ponting’s photographs owed much to an extensive career that had produced celebrated images of Japan — including of snow-capped Mount Fuji, which he had climbed.

The opening title of Great White Silence. Internet Archive

Ponting’s images were swiftly published and displayed for a British and global public eager to venerate the heroic Scott and view the wondrous world of Antarctic ice. His first expedition film, the thirty-minute With Captain Scott RN to the Pole, was released in November 1911. Other short films and gallery exhibitions of his photographs would follow. All were designed to make money for the expedition. But they weren’t standalone films as we recognise today, and in the first decade after the expedition, Ponting and others delivered what were called “cinema-lectures.” These lectures — labelled “synchronised lecture entertainments” by Australian literary scholar Robert Dixon — involved an in-person lecturer projecting slides and moving images, sometimes with on-stage physical artefacts and props, accompanied by music. They also sold merchandising: not only copies of various expedition books but also photos and even plush toys including “Ponko the Penguin.” (Ponko was Ponting’s nickname.) By May 1919, Ponting had delivered 1000 of these lectures.

Such a schedule was obviously untenable for a working photographer and Ponting had always wanted to make a standalone feature film. Once he had published his own narrative and reflection on the expedition, Great White South (1921), he began editing the film down from 25,000 feet of 35mm film.

The film tells a simple story in eighty minutes. The expedition sets out from New Zealand in late 1910, it encounters icebergs and sea ice on its voyage south, it unloads its supplies and builds its hut, and the men encounter penguins (which they compare with Charlie Chaplin), seals, orca, and skua birds. Scott and his party attain the South Pole on 17 January 1912, but in second place, and perish on their return. Like other silent films, Ponting used title cards to explain the story and action. The film uses both still and moving images.

Before the tragic denouement, the film focuses on the liveliness of the men and the animals they encountered. The men are hale and hearty, whether dragging their sledges or playing a game of soccer. The animals are curious and feisty, if locked in the great struggle of nature. In one dramatic scene, Ponting captures a mother seal rescuing her pup from the water just as a pod of orca bears down on them. In an extended scene with Adelie penguins, an interloping nest squatter is confronted and despatched.

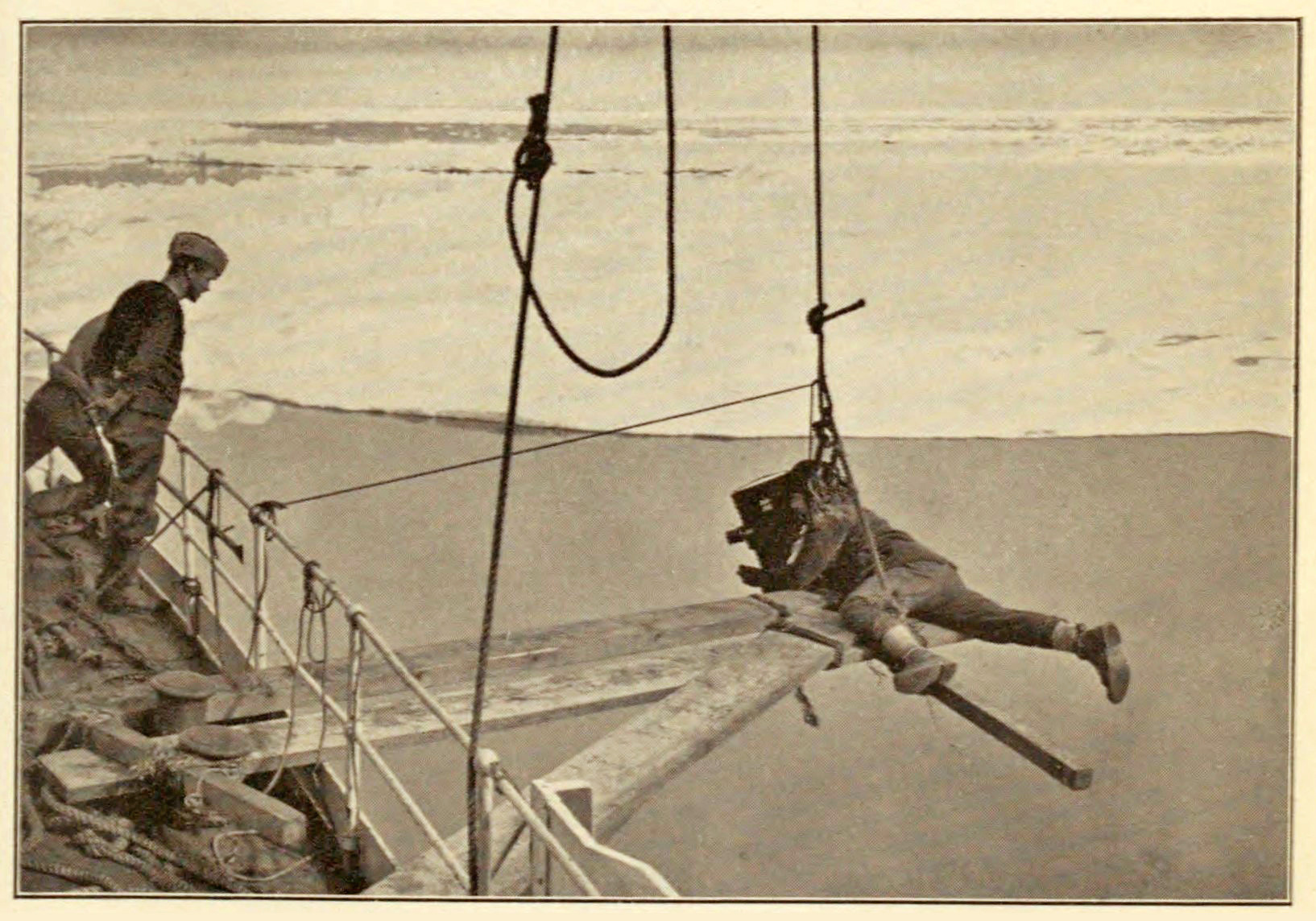

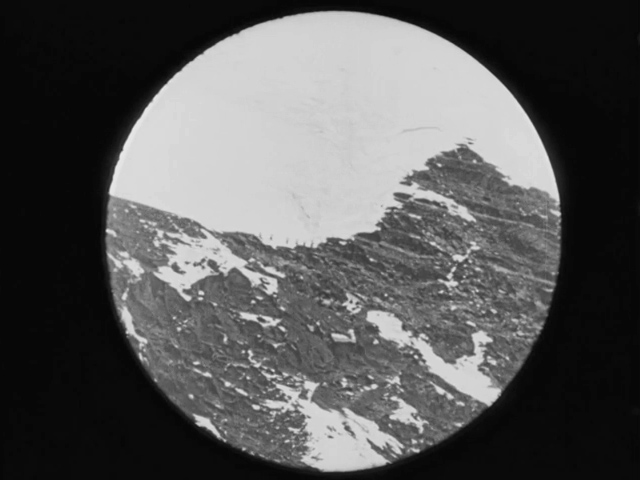

And all around them is ice. As the photo above shows, Ponting went out on a limb, quite literally, to film Terra Nova’s bow cutting through the sea ice. The film features some of his iconic images of glaciers and icebergs, his mastery of light and shade revealing the intricate faces and textures of these massive and ever-changing blocks of ice. He did not, however, photograph the “polar plateau” — the great expanse of the Antarctic ice sheet — as he was not a member of the pole party. Instead, Great White Silence depicts Scott’s team as small black shapes moving on a diorama.

For Ponting, as for others at this time, ice of this magnitude was still interpreted through the Romantic ideal of the sublime. As the first title card of the film states: “The Antarctic Continent is an ice clad wilderness of dazzling whiteness and appalling silence. It is the home of Nature in her most savage and merciless moods, and it is there that the hurricane and the blizzard are born.” The ice in this film is a stage for heroic action. But it is not exclusively so, since it is also a site of conviviality and sociability among the men of the expedition.

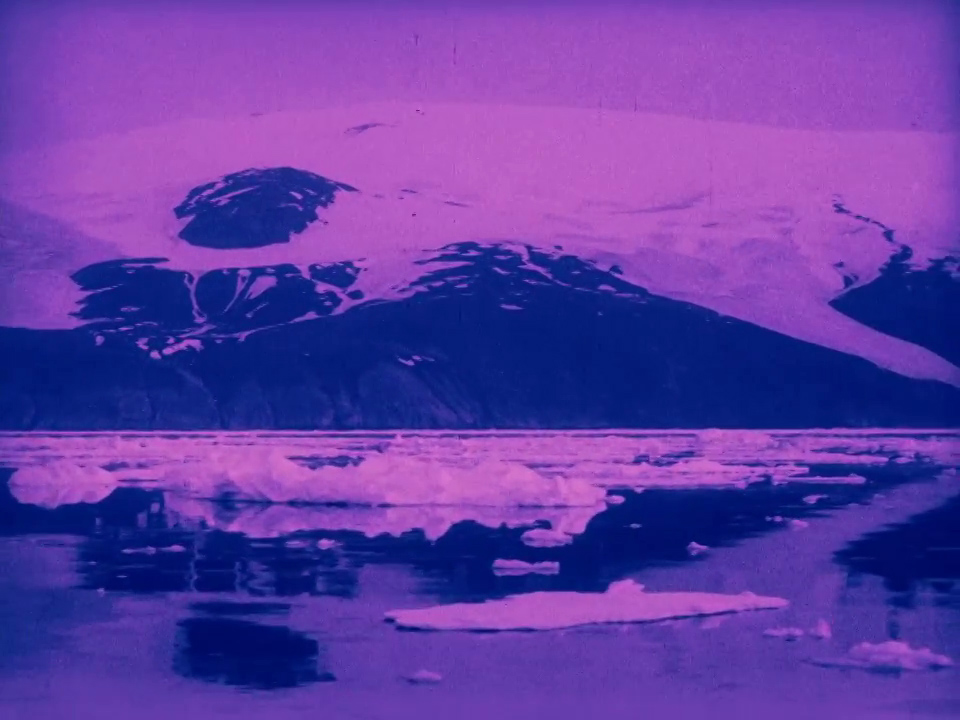

Antarctic ice taking on a different character with colourful film tints. Internet Archive

One surprise for a modern audience might be in the colours of Great White Silence — it was not a simple black and white film. Like other filmmakers of the era, Ponting used colour tints to indicate different atmospheres, times and moods. Some daytime scenes are shown in what might be called sepia, but seem at times a vibrant tangerine and at others a duller yellow. Evening scenes were tinted in a stunning magenta. Some scenes with ice and wind were dyed blue, and several scenes with the wildlife were tinted in emerald.

While Antarctica’s ice was a stage for heroic, imperial action, Nanook of the North follows an Inuit man and his family as they live their everyday lives. The seventy-nine-minute film is known in cinema history as being the first documentary — indeed the word documentary was coined in 1926 to describe it. It has been closely studied and debated, with a focus not only on the colonial and racialised conditions of its production, but also the question of whether it is a documentary or a fiction.

The opening title of Nanook of the North. Internet Archive

Its writer and director, Robert Flaherty (1884–1951), was not a trained photographer or director, but had begun his professional life as a mineral prospector in the Hudson Bay region. Now pursuing a career in documentary film-making, he attempted between 1914 and 1916 to make a film of Inuit life but had burned his highly combustible nitrate film by accident while editing it. He returned north between August 1920 and August 1921 to shoot what would become Nanook.

The film episodically depicts the life of “Nanook” (already the documentary nature of the film begins the disintegrate, as the man’s name was actually Allakariallak), his wife Nyla (not actually his wife, real name Maggie Nujarluktuk) and their children. The first scene shows Nanook and family at a fur trading post, a recent imposition in that part of Arctic Canada but part of a centuries-long Western intrusion. This is perhaps the most controversial scene of the film, given its hackneyed portrayal of the encounter of the simple and cheerfully ignorant native with the advanced Western technology of the gramophone. Yet it is followed by scenes of skilful endeavours in and around ice: walrus and seal hunting, fishing, fox trapping, and building a magnificent igloo. The children play with husky pups; Nanook sometimes seems to ham it up for the camera.

Nanook adds clear ice to his igloo to allow light in, his snow knife made of bone essential to the task. Internet Archive

Nanook is a film of a man and his family in their home. The action of the film happens around the village of Inukjuak, an area long inhabited by Inuit on northern Quebec’s Ungava Peninsula but now also the site of a modern fur trading post. (The fur-trading company Revillon Frères sponsored Flaherty’s work.) As for all Inuit, it was a home made from and with ice. Almost no other people on Earth make their home in ice as the Inuit do, with the result that no other people on Earth know ice as the Inuit do. As climate change undermines the cryosphere, the Inuit today assert their “right to be cold,” as famously argued for by Inuit leader Sheila Watt-Cloutier. The tradition of hunting at which Nanook is clearly so skilled is being undermined by sea ice failing to form as it once did or melting quicker.

The final film in this cryospheric trilogy takes us to the world’s tallest mountain. The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India had declared Chomolungma the tallest mountain on Earth in 1856 — following surveys at some distance from the peak in the first half of that decade — and imposed the name Everest. The mountain was only more closely approached by European explorers and scientists after European explorers and empires had beaten down the doors of Tibet in the early twentieth century.

The Epic of Everest, which premiered on 9 December 1924, was filmed and produced by expedition member John Noel (1890–1989). Of those on the expedition, Noel had perhaps the longest association with the Himalaya. After taking art training in Florence, he joined the British Army; his regiment was posted to India, where he began to see and photograph the Himalaya. In 1913 he notoriously and illegally travelled in disguise into Tibet, contravening the bar on entry to foreigners; he was discovered and deported having got within forty miles of the mountain. After the First World War, the Dalai Lama relaxed the entry restriction and granted permission for an expedition sent by the Royal Geographical Society of London.

The opening title of The Epic of Everest. Internet Archive

The society’s campaign had several stages. A reconnaissance expedition in 1921 attempted to understand the best route of ascent. The next in 1922, which Noel joined as photographer, aimed to reach the summit, although without success. That expedition led to a film, not so widely distributed or successful, titled Climbing Mount Everest. Without the achievement of the summit, that film depicted Tibetan life and landscapes at greater length.

While ice in Nanook and Great White Silence is omnipresent, in Epic, the mountain and its snow and glaciers seems especially imposing and characterful. While Flaherty did not detail the complex cultural geographies of the Inuit and their home of ice, Noel emphasises the religious and mystical cosmologies encircling the great mountain. Early in the film, Noel uses the Tibetan name: Chomolungma, which he translates (as many have) as “Goddess Mother of the World.” The Australian historian of Buddhism, Tibet and the Himalaya, Ruth Gamble, explains that Chomolungma has undoubtedly been the Tibetan name for the mountain for centuries. It is the abode of the goddess Miyo Langsangma, which Gamble translates as “the immovable, good woman of the willows.”

Noel’s is certainly a superficial reference to the Goddess and her abode of ice and snow rather than a display of reverence. The opening title card of the film emphasises domination: “Since the beginning of the world men have battled with Nature for the mastery of their physical surroundings… In this struggle men have now explored tropical forests, polar ice and lofty mountains, sensing the extremities of heat and cold and reaching the ends of the world at either pole. But one great task still remains, THE CONQUEST OF EVEREST.”

The climax of the film is, perhaps obviously, the thrust towards the summit, followed by the death of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine at or near it. (In macabre timing for the centennial, a National Geographic documentary team discovered Irvine’s boot and some of his bodily remains this past September — Mallory’s had been found in 1999.) These last moments are also among the most distinct visual moments of the film. Noel filmed the final ascent from a distance of more than two miles using a telephoto lens. The climbers appear as moving black specks; the visual overlap with Great White Silence is notable, although Ponting’s black dots were staged and Noel’s miniscule figures where the real thing.

Capturing the epic with a telephoto lens. As The Epic of Everest’s title card claimed: “4,000 ft. above and 2 miles distant this picture is the longest distance photograph of its kind ever taken in the world.”

Like Great White Silence, Noel also tinted segments of his film. Chomolungma, its snowy mists and jagged ice — the main body of ice being the East Rongbuk Glacier on the mountain’s north face — appears not only in black and white, but also in icy blue, turquoise, magenta and dusky red. While Ponting used his still photographs extensively, Noel’s film records the ever moving and frigid airs of the mountains, the changing light and shadows. Epic’s opening scene is a magnificent time lapse of sunrise over the mountain, its closing scene a time lapse of the mountain entering darkness. Noel’s film is, indeed, “hauntingly beautiful,” as one early review put it.

The sun sets on Chomolungma, the lives of Mallory and Irvine, and the Epic.

This anniversary is a good opportunity to look again at these captivating and historic films — or indeed, watch them for the first time, and together. Each is freely available to watch on the Internet Archive, that great hope and repository of out-of-copyright and public domain culture. Great White Silence and Epic of Everest were masterfully restored by the British Film Institute in 2011 and 2013 respectively, to which they added contemporary musical accompaniment.

Looking back to these films a century after they first flickered onto screen, we see them through a profoundly different lens. If Captain Noel considered his filmic challenge was to “make the spectator feel the immensity of [the] struggle of men against nature” (to quote famed film historian Kevin Brownlow), then today’s viewer knows very well that our challenge is to reverse that dominance, the threat that carbon polluting humanity is to the existence of ice. •