It’s a long time — forty-five years in fact — since government funding of tertiary education peaked in Australia at 1.5 per cent of GDP. These days, the government contributes 0.8 per cent, or just over half that proportion. Back in 1975, around 277,000 students were enrolled in higher education; by 2016, the number had increased fivefold to 1.46 million.

Those figures capture the essential story of Australian universities over the past forty-five years: massive growth combined with declining public investment.

The suddenness of the Coronavirus pandemic has hit Australian universities very hard, but the acuteness of their problems has been greatly exacerbated by trends that have been building for decades. The federal government has offered much less support to universities than to other deeply affected parts of the economy, and many conservative commentators have used this as yet another occasion to criticise the sector.

Backbench Liberal senator James Paterson, for instance, says that “universities have not done themselves many favours in recent years,” as if reacting to the diminishing level of public support, especially from his own party, has not been a central driver of the strategies for survival universities have had to adopt.

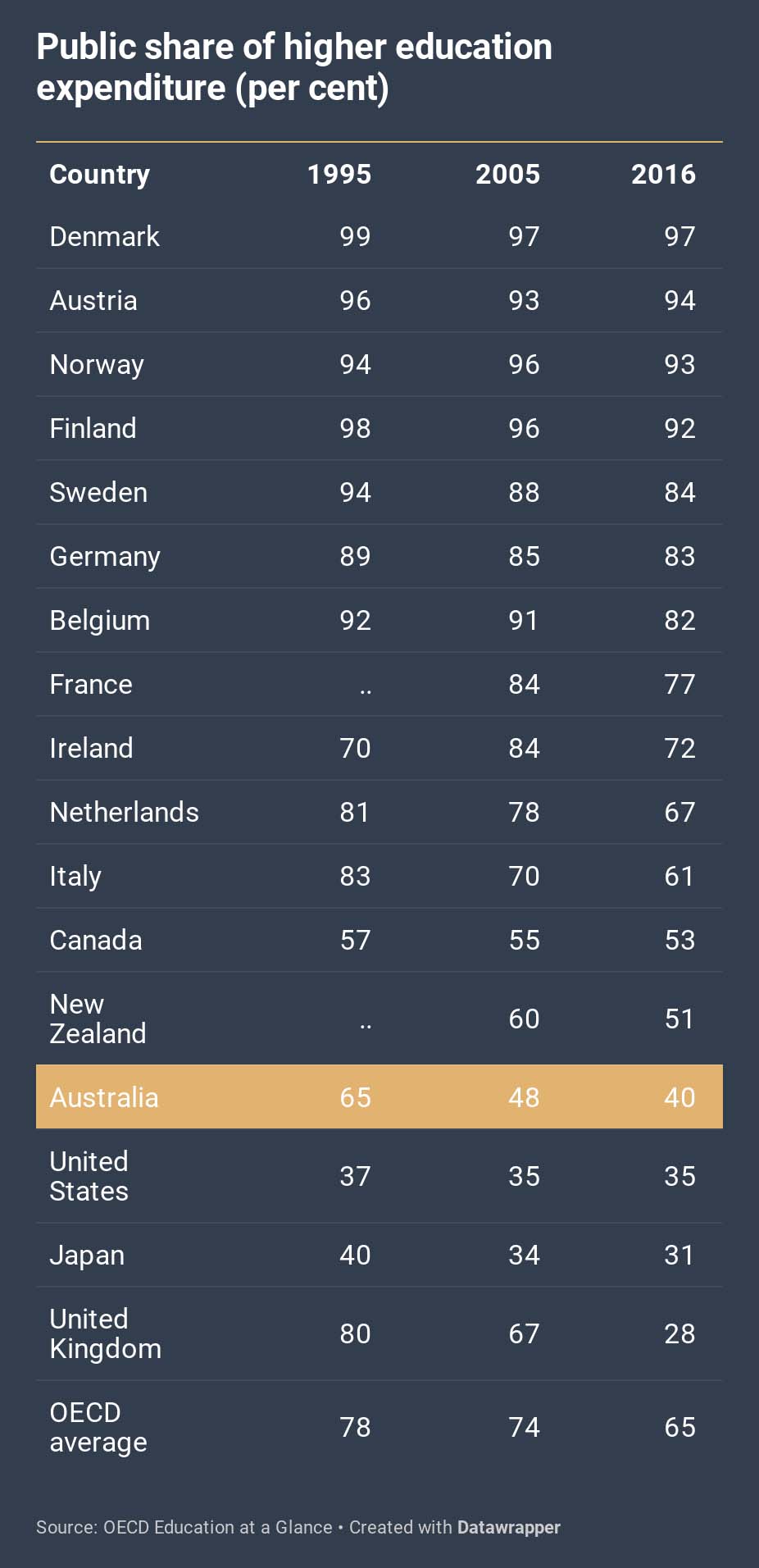

Over the period 1989 to 2017, domestic student enrolments more than doubled, according to former Melbourne University vice-chancellor Glyn Davis, yet the federal government’s contribution to operating costs rose only by a third. Between 1995 and 2005, when OECD governments increased their contributions to tertiary education by an average of 49.4 per cent after inflation, the Howard government provided no real increase at all.

In seven of those comparable countries, as the chart shows, governments contribute more than 80 per cent of higher education spending. In just four — including Australia — they contribute less than half. The only country whose public share has dropped more sharply than Australia’s is Britain — initially under the Blair–Brown Labour governments, but much more quickly after the election of the Conservative government in 2010.

No data available on Switzerland. The Danish figure in the 2016 is old, but still broadly accurate.

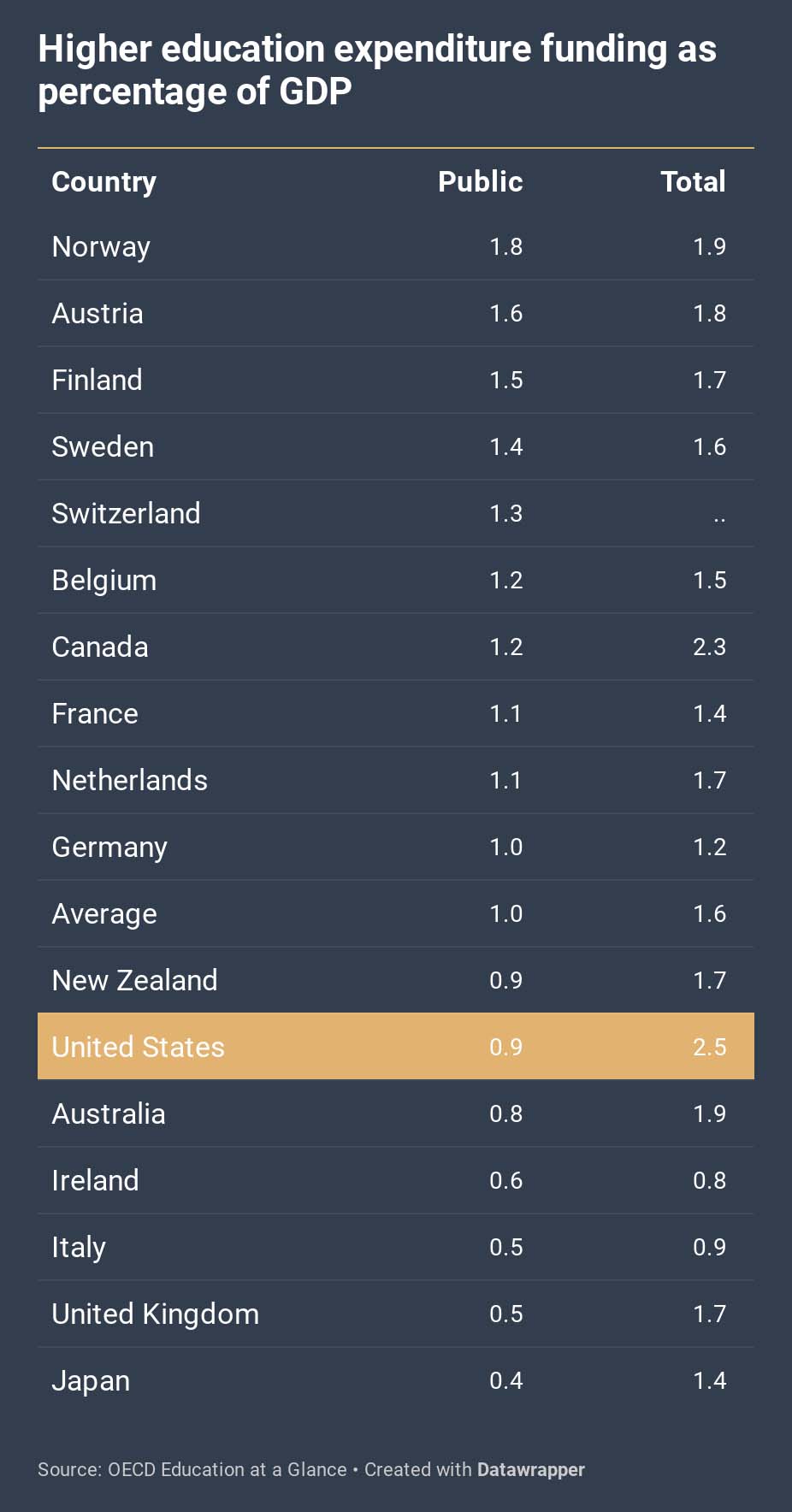

As the second chart shows, Australia also ranks in the bottom third of countries according to the proportion of GDP spent on higher education. With a government contribution of just 0.8 per cent of GDP, it ranked twenty-fourth among the thirty-seven OECD countries.

That chart also shows that Australia’s total spending on tertiary education is in the top half of OECD countries. The difference is explained by two principal sources of private funding: the fees paid by Australian students, and the income from international students.

No data available for Denmark.

A crucial year in the development of Australian tertiary education was 1989. Among the dramatic changes made by Hawke government education minister John Dawkins was the introduction of the HECS student fee scheme. In the early 1990s, domestic students were charged about 20 per cent of the cost of their degrees, but in recent years that share has averaged around 40 per cent. The fees paid by domestic students in Australia are among the highest in the OECD.

More important, though, has been the growing number of international students. Back in 1989, just 21,000 foreign students were studying in Australian universities; by 2016, the figure was 391,000, an almost twentyfold increase. The biggest increase has come this century: enrolments from China, for instance, have grown twentyfold since 2000 and now comprise more than a third of all international students.

Overseas student fees rose from 17.1 per cent of university revenue in 2004 to 23.5 per cent in 2017. By then, international student revenue had exceeded an annual $9 billion, making it the largest source of private revenue for public universities. (Other industries also benefit from the presence of international students, of course.) Tertiary education is one of Australia’s greatest export successes, and now ranks third behind the leading earners, coal and iron ore.

With the huge growth in overall numbers, universities have had to spend massively on buildings, technology and other infrastructure. That means cutting recurrent costs and finding more economical ways of operating. As Glyn Davis points out, the staff–student ratio fell from 1:12 in 1991 (when many of the current crop of MPs were still studying) to 1:21 in 2007.

The composition of staff is also changing: cost-saving casuals made up 14 per cent of university staff in 1988 but 23 per cent in 2016. With permanent academic staff often having other demands on their time, this suggests that more than a quarter of the teaching load is now borne by casual staff.

Over three decades university finances have been transformed. In 1990, for example, 86 per cent of Sydney University’s income came from government funding. By 2018 the figure was just 28 per cent. The essential difficulty with which universities wrestle is inadequate public funding. Now, under the pressure of the pandemic, it suits the education minister and his colleagues to blame universities and “their overexposure to the international student market.”

Education minister Dan Tehan says that “there is a perception that the focus on international students has taken away from the core responsibility of our universities: to educate and skill young Australians.” This is a common but essentially misplaced criticism. In fact, the income from international students cross-subsidises the teaching of Australian students, who would have even fewer teaching resources directed at them if the international market dried up.

As Glyn Davis wrote before the pandemic, “By withdrawing public funding, government has deeded Australia a university system that relies heavily on the families of Asia. If our neighbours tire of cross-subsidising Australian students, the number of local places would shrink rapidly.”

The pandemic has thrown university budgets into chaos. No other sector so badly affected by the coronavirus has been treated with so little sympathy, let alone tangible support. It seems the government’s cultural antipathy to universities overrides all else. •