Clive Palmer’s battle with Mark McGowan and his Labor colleagues in Western Australia might seem like an unprecedented use of sheer willpower to bend a government to a miner’s will. But the multimillionaire’s litigiousness recalls the titanic clashes between Western Australian entrepreneur Lang Hancock and the Coalition government’s Charles Court in the pioneering days of the iron ore industry. Whether events will continue to play out in parallel will become clearer once the courts rule on the government’s attempt to block Palmer’s latest legal challenge.

Langley Frederick George Hancock was born in Perth in 1909, the eldest son of pastoralist George Hancock and his South Australian–born wife Lilian. After gaining his leaving certificate — having proved “an able if not outstanding student,” according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography — he helped his father on the family’s sheep-farming property at Mulga Downs in the Pilbara. There he gained a bushman’s knowledge of the land and an amateur’s understanding of geology. At the end of the second world war, Hancock resumed a business partnership with a school friend, Peter Wright. The two men had merged their two prospecting companies into a partnership known as Hanwright in 1938.

In that same year, with Japan at war with China and wider conflict in the Pacific looming, prime minister Joseph Lyons placed an embargo on the export of Australian iron ore. To demonstrate the need to prevent sales overseas, Lyons commissioned a report on the extent of Australian iron ore deposits from his senior geologist, W.G. Woolnough. Woolnough obligingly reported that Australia’s accessible high-grade iron ore was sufficient only for the needs of the local steel industry. If exports were to continue, said Woolnough, the country might run out of ore in two generations. The Woolnough report created a myth, but such a powerful one that it governed resources policy for more than two decades.

Large but unconfirmed deposits of iron ore in the remote Pilbara region had been spoken of since the late nineteenth century. It was Hancock, pioneering a new technique for aerial prospecting, who established their existence in the 1950s. As he told the story, the epoch-making discovery occurred during a thunderstorm in November 1952: forced to fly his Auster aeroplane unusually low over the Hamersley Range, he noticed what looked to be significant deposits of iron ore. Whether true or embellished, the story helped turn Hancock into a household name.

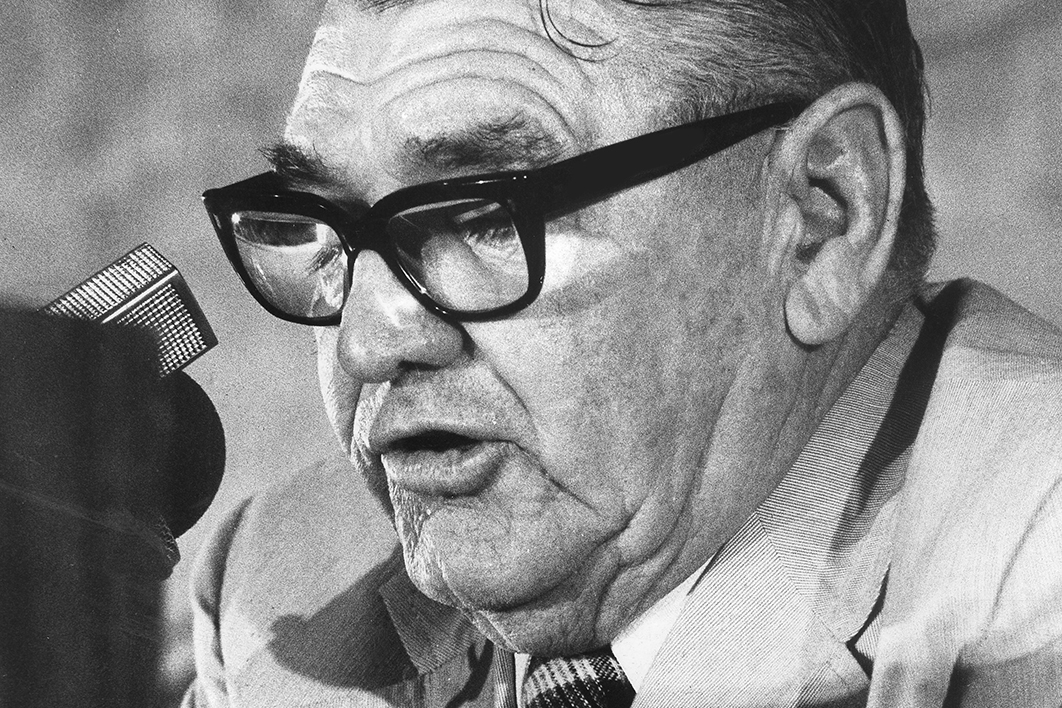

The problem was that any iron ore that was present in the Pilbara was valueless unless it could be mined and exported. After the Liberal–Country Party Coalition came to power in Western Australia in 1959, Hancock worked closely with the state government to overturn the federal embargo. Among premier David Brand’s ministers was Charles Court, who would succeed Brand in 1974 to become one of the state’s most electorally successful premiers.

In 1960 Brand and Court, who was industry minister, forced the hand of the federal government by calling for tenders to mine and export a known iron ore deposit at Mount Goldsworthy, on the northern fringe of the Pilbara. Hanwright was among those bidding for the leases. With Australia suffering a significant balance-of-payments deficit, prime minister Robert Menzies announced a trial relaxation of the iron ore embargo to see if deposits of this potential export earner could be found.

Menzies was soon overwhelmed by the world-ranking discoveries in the Pilbara. Hancock had forged a partnership with the English chairman of Rio Tinto, Sir Val Duncan, who sent out a geologist to examine and confirm Hancock’s 1952 discoveries. Hancock told Duncan that the WA government was in acute need of revenue, and that Duncan should immediately seek a mining lease by promising to build a Western Australian steel industry.

In the meantime, Hancock had antagonised Brand and Court, who preferred an Anglo-American consortium over Hanwright to mine the deposits at Mount Goldsworthy. The two government figures were suspicious of Duncan’s association with Hancock and doubted Duncan’s capacity to create a steel industry in Western Australia. Hancock was disappointed when the state government rejected Duncan’s offer, but not defeated.

In 1962, the ninety-year-old global mining company Rio Tinto merged with the Zinc Corporation to create Rio Tinto Zinc and an Australian subsidiary, Conzinc Riotinto of Australia, or CRA. That year, Rio Tinto geologists made one of the greatest of all mineral discoveries when they found a rich iron ore mountain named Tom Price just outside the area Hancock had disclosed to Val Duncan.

CRA formed a partnership with the American steelmaker Kaiser Steel to mine Tom Price and took to the WA government a proposal for an iron ore export operation and ultimately a local steel industry. To ease the path to an agreement, CRA distanced itself from Hanwright by offering Hancock’s company a generous royalty deal of 2.5 per cent of the value of all iron ore sold in the area of his discoveries, including Mount Tom Price. That deal was the making of Hancock’s fortune.

But Hancock’s mining story didn’t end there. Charles Court had been busy helping establish an iron ore industry in Western Australia. Under agreements ratified by acts of parliament, four companies were building their own ports and railways. Together, Court believed, they would satisfy Japanese demand for Australian iron ore.

By 1964 the new Pilbara iron ore companies were established but had yet to build their mines, ports or railways. Hancock seized the opportunity by teaming up with the American industrial and shipping magnate, Daniel Ludwig. With Hancock in the wings, Ludwig approached Court with an ambitious and unexpected proposal.

Under what it called the Ludwig Plan, the company would mine other areas discovered by Hancock at Nimingarra and Yarrie and finance a super-port at Cape Keraudren that could accommodate 166,000-ton ships. Ludwig also undertook to service all other iron ore projects and lead the financing and construction of their roads and railways. This would bring together in one operation all the infrastructure for the iron ore mines in the Pilbara.

To Hancock’s lasting chagrin, Court rejected the offer, describing it as the “Ludwig Benefit.” Once again Hancock pressed on, alone among Pilbara operators in believing the market for Australian ore was nowhere near saturation. Between 1966 and 1968 he continued his aerial prospecting, staking out numerous mining tenements over large swathes of the Pilbara. These “temporary reserves” gave their owners the right to develop mineral deposits on terms and conditions ultimately approved by the state government. Hancock then brought in big foreign mining companies, such as Armco Steel Corporation, to develop his discoveries.

Hancock’s ambitious development plans started to clash fundamentally with those of Court, who believed that the Pilbara’s iron ore should be developed by a few mining companies operating under state government supervision. He regarded many of the temporary reserves staked out by Hancock as more logically belonging to what he called the established companies’ “areas of influence.” By contrast, Hancock believed that the finder of mineral deposits should determine how they were developed. In some ways, his struggle with Court resembled the fight of the squatters to graze sheep where they could despite the orderly plans of the governor of early Sydney, George Gipps.

By 1971 Hancock had established a weekly newspaper, the Sunday Independent, which swung all its political influence against Brand and Court. He succeeded in tipping that year’s state election in favour of John Tonkin’s Labor Party and casting his enemy, Court, into opposition.

Yet Tonkin’s government quickly came to side with Court over Hancock. With Court’s blessing, Tonkin cut the Gordian knot represented by Hancock’s numerous lease applications and half-negotiated agreements. He declared that Hancock could retain rights to areas known as McCamey’s Monster (now BHP’s Jimblebar mine), Rhodes Ridge and Western Ridge. All other areas claimed by Hancock, including the rich Angelas deposits, would revert to the state government.

Hancock derided Tonkin’s move as the “Great Claim Robbery” and challenged it, unsuccessfully, in the Supreme Court. This meant that Charles Court’s “spheres of influence” plan for the Pilbara would win out against Hancock’s grandiose development plans, including his proposed unified rail systems and the ports he envisaged being created using atomic explosions.

Court succeeded Tonkin as premier in 1974 and held power until 1982. Hancock never achieved his aim of actually owning a mine, but he was influential in conservative politics, calling for Western Australia’s secession from the Commonwealth and strongly supporting Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s government in Queensland.

Clive Palmer’s career parallels Hancock’s in many ways. Palmer, a Queenslander, made his fortune in Gold Coast real estate and developed close links with Queensland’s conservative parties. In the 1980s he branched out into nickel, coal and iron ore through his company Mineralogy, which went into partnership with Chinese company CITIC. Palmer eventually fell out with CITIC, whose owners took him to the Supreme Court of Western Australia and received $200 million in damages.

In 2010 Palmer joined forces with other mining magnates, including Twiggy Forrest and Lang Hancock’s daughter, Gina Rinehart, to successfully oppose Labor prime minister Kevin Rudd’s mining tax. By 2013 he had abandoned his links with the Queensland Liberal National Party and formed the Palmer United Party. At that year’s federal election he won the seat of Fairfax and his party won a number of Senate seats.

Palmer relaunched his party as the United Australia Party in 2018. Although he didn’t win any seats in the 2019 federal election, he spent more than $60 million on advertising, helping to tip a close election in favour of the incumbent Morrison government. The campaign included advertisements pointing to the danger to Australia posed by the Chinese Communist Party.

Now, in 2020, Palmer has confronted popular WA Labor premier Mark McGowan, just as Hancock challenged Charles Court in the 1960s and 1970s. In July, Palmer announced a court challenge to the WA government’s decision to close the state border during the Covid-19 pandemic. The “unconstitutional” border closure, Palmer alleged, would “destroy the lives of hundreds of thousands of people for decades.”

Perhaps recalling Palmer’s assistance during last year’s election campaign, the Morrison government initially supported the legal challenge. In August, however, it withdrew from the action. By then, McGowan was determined to wage what he called a war with Clive Palmer, “and it’s a war we intend to win.” McGowan’s popularity threatens Coalition seats in next year’s state election and possibly the next federal election.

Palmer wasn’t deterred from mounting an even more audacious legal action. Mineralogy was pressing an arbitration claim against decisions made in 2010 by the government of McGowan’s predecessor, Colin Barnett, about Palmer’s Balmoral South iron ore project. Palmer had wanted to develop the project as a mine and sell it to a Chinese-owned entity, a proposal Barnett refused in 2012. After six years of litigation, Palmer and his lawyers made the claim that his proposals had been unjustly refused, costing him billions of dollars.

In much the same way as Tonkin acted in 1971, with Charles Court’s support, McGowan’s government claimed that Western Australia faced the possibility of having to pay as much as $30 billion damages to Palmer. If successful, McGowan argued, hospitals, schools and police stations would have to close. To head off the prospect, McGowan rushed through legislation terminating Palmer’s legal claim, preventing him from lodging another and cancelling his right of appeal. Whether McGowan’s legislation will be as successful as Tonkin and Court’s against Lang Hancock remains to be seen.

What is clear from the cases of Hancock and Palmer is the enormous economic and political power of the mining industry, especially when it is exercised by charismatic entrepreneurs prepared to defend their interests in the business world, the political arena and the courts. Also evident is the WA government’s preparedness to use the power of the sovereign state to act retrospectively to cut those entrepreneurs down to size. •