In the wake of Joe Biden’s narrow victory in 2020 and the abortive Trump insurrection that followed, one important fact stood out for Marcy Kaptur, a Democratic congresswoman from Ohio. Republicans now represented nearly 70 per cent of Congressional districts where most household incomes were below the national average.

“How is it possible that Republicans are representing the majority of people who struggle?” she asked. “How is that possible?”

Four years later, an even larger number of working-class voters have deserted the Democrats for a faux-fascist and convicted con-artist. Evidently, the Democratic establishment is no closer to comprehending, let alone reversing, this long-term trend.

But then neither are a host of centre-left parties around the world that have been struggling for some time to retain the support of disenchanted workers drawn to the (police) siren call of right-wing populist leaders. That may soon include Australia as we head into an election where Labor is leaking support to nearly all points of the political compass.

So the publication of Timothy Shenk’s Left Adrift: What Happened to Liberal Politics could not be timelier. His subject is the long-term de-/realignment of electoral politics in the United States, Britain, Israel and South Africa. It’s not just that so many of “the people who struggle” have shifted to the right. It’s also that more affluent and highly educated voters have swung leftwards. Accompanying this transformation has been an increasing political polarisation fed by culture wars around race, gender, health, history and climate change.

Shenk offers not so much an explanation of these cross-cutting trends as their back-story, told through the careers of two low-profile but highly influential American political consultants, Stanley Greenberg and Douglas Schoen. Coming of age politically in the 1960s, they witnessed the first cracks in the multiracial working-class coalition that had powered the Democrats since the days of FDR.

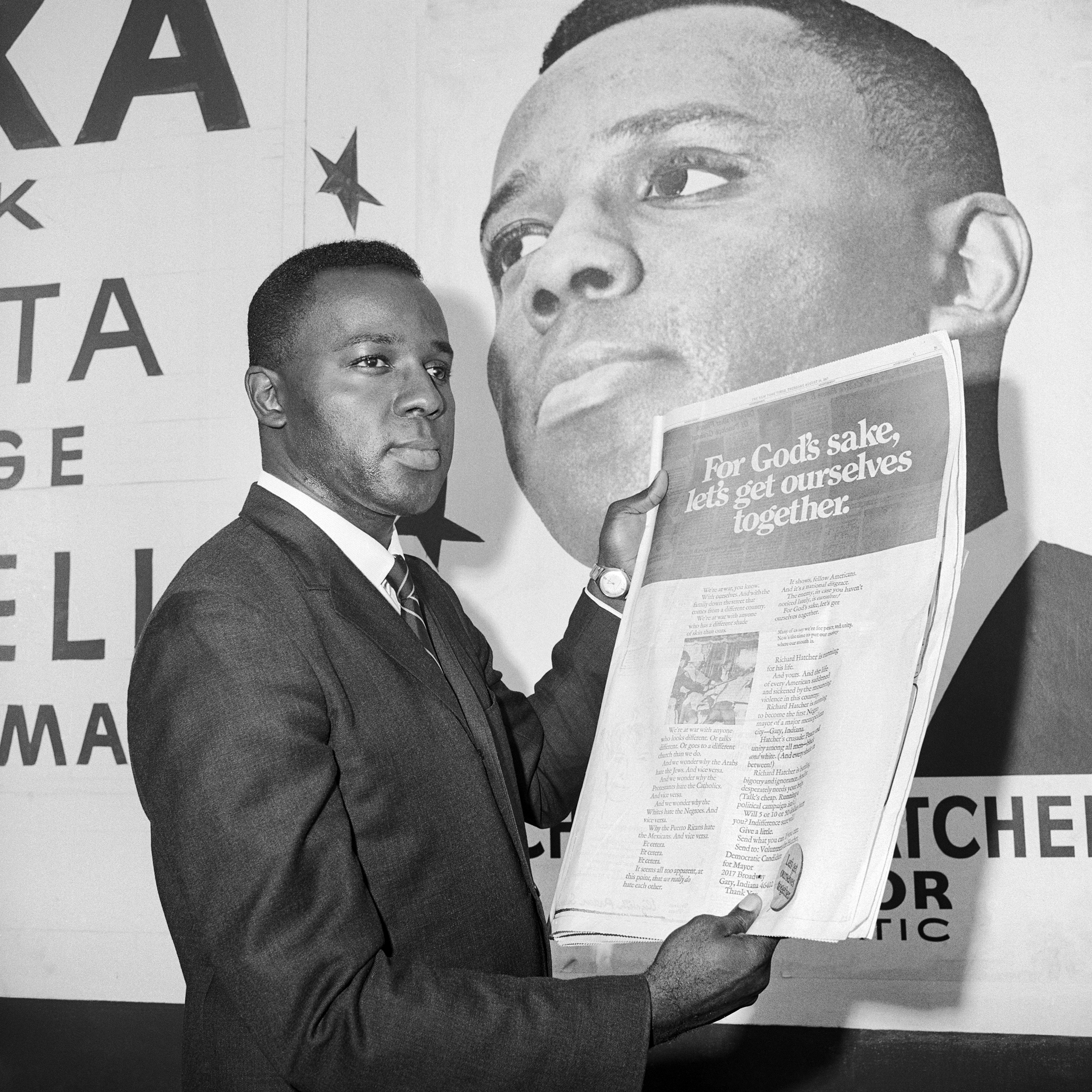

As it happened, so did I, on 7 November 1967 to be exact. On that day I was campaigning in Gary, Indiana, on behalf of a young black lawyer named Richard Hatcher (pictured above), who had earlier won the Democratic primary for mayor. Unfortunately, as a result of Hatcher’s refusal to endorse in advance his party’s white powerbrokers’ picks for police chief and other important positions, they were now openly backing his white Republican opponent. In a city where African Americans already constituted half the population, this was bound to be a racially divisive election.

Sure enough, Hatcher had to send out a national call for both money — Robert Kennedy was a high-profile fundraiser — and enough white Democrats from outside Gary to cover its Anglo precincts on election day. That is how I and another volunteer from Chicago ended up being confronted late in the day at a polling station by four burly white steelworkers. While I was forcefully being shoved into some bushes, my more assertive colleague had his nose broken.

Shortly after our assailants departed, a Gary police car magically appeared. Though we hardly needed encouragement, the white cops quickly advised us to leave the city for our own safety. So, sadly, we missed out on the party to celebrate Hatcher’s (narrow) victory thanks to 96 per cent of black voters and just 12 per cent of whites.

So what were liberal Democrats like Shenk’s two main protagonists to make of this election and the Democratic party more generally in those racially charged and often turbulent times, especially following the assassination of RFK and the election of Richard Nixon a year later? More specifically, what would it take to resurrect FDR’s multiracial coalition?

Where have all the workers gone?

During the 1970s Greenberg and Schoen undertook doctorates at Harvard and Oxford, respectively, to make sense of why American and British workers were starting to desert their traditional centre-left champions. What they discovered is that the relatively recent migrations of black people to previously all-white enclaves — whether from the American deep south to the industrialised north or from the Caribbean to Britain’s inner-cities — had exposed a deep vein of white working-class racism. Subsequent economic dislocations and political provocations only served to deepen these racial divisions.

Greenberg’s American surveys demonstrated that “white Democratic defectors express a profound distaste for blacks, a sentiment that pervades almost everything they thought about government and politics.” Schoen’s polling of public opinion in Britain — in the wake of Enoch Powell’s anti-immigration crusade — revealed that racism was an equally important component of white working-class identity there.

But the group Greenberg would later dub “Reagan Democrats” also harboured resentments against “Wall Street, free trade and globalisation, coupled with a fear of immigrants.” The question for both Greenberg and Schoen was how these voters could be brought back into the Democratic fold.

For the past four decades Greenberg’s enduring commitment has been to help the Democrats (and centre-left parties elsewhere) build an enduring coalition of wage earners across a broad spectrum of industries and occupations — whether or not they identified themselves as “working class.” His starting point was always “an ambitious economic program” focused on full employment, tax relief and universal provision of essential services (especially health, education and childcare) that benefited all workers, regardless of race (or gender). In Greenberg’s view, however, reclaiming disaffected white workers would also require an assault on corporate elites, as well as “a shift to the centre on polarising social issues.”

While Schoen agreed with Greenberg that the Democrats had to “turn down the volume in the culture wars,” he rejected Greenberg’s economic populism as an equally divisive and unpopular effort to revive the “class war.” The only hope for Democrats was to embrace most of Reagan’s neoliberal economic and fiscal policies while offering a carefully curated smorgasbord of issues that appealed to different demographics and special interest groups. This would enable the Dems to contrast themselves as political unifiers compared with their culturally polarising Republican opponents.

What Greenberg and Schoen now required for their differing approaches was a messenger. They both eventually found one: ironically, “it just happened to be the same person.” Bill Clinton.

Making the world safe for the centre-left?

Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign serves as the pivot point for Shenk’s narrative. It enabled Greenberg and later Schoen not only to test their competing strategies but also to export their polling and messaging expertise to other centre-left parties around the world anxious to replicate the Americans’ recipes for electoral success.

Soon both Greenberg and his partners (James Carville and Bob Shrum), as well as Schoen and his associate Mark Penn, would be competing for clients in Britain (Labour’s Tony Blair), Israel (Labor’s Shimon Peres and Ehud Barak) and South Africa (the ANC’s Nelson Mandela). Unsurprisingly, their respective interventions ended up reprising — with some significant variations — the trajectories of Clinton’s campaigns, including how these rival consultants would be regularly swapped for one another.

In fact, stripped to its bare bones, the overarching storyline that emerges from Shenk’s compelling narrative of these globally consequential engagements could provide the basis for a darkly comedic Netflix series running over three seasons. Working title: The Consultants (The Good Fight would have been better).

Season 1. After spending years in the wilderness, a centre-left party calls on Stanley Greenberg, who advises them to build a coalition of working-class voters by responding to their kitchen-table issues and animus toward powerful elites with an economically populist agenda. After getting pushback from the party’s inner circle and influential donors, its leader waters down Greenberg’s strategy and softens his messaging to appeal to a broader range of more affluent liberal-minded voters. This results in the party’s return to power but with a more ambiguous mandate and uncertain support base.

Season 2. Once in office, the new centre-left government runs into some significant headwinds, including some of its own making. But the most important of these involves abandoning most of whatever remained of its economic populism in the face of resistance from powerful industry groups, central banks and treasury officials. Faltering in the polls with the approach of an upcoming election, Greenberg’s firm is replaced with Schoen and Penn, who guide the party closer to the centre. The outcome is a more lacklustre electoral victory, but this time with declining working-class support accompanied by a rising tide of cultural polarisation.

Season 3. Several decades later, whether in power or not, the centre-left parties remain adrift as their working-class base keeps eroding and right-wing leaders come to dominate their nations’ political agenda. As for our two protagonists, Greenberg remains unrepentant about the need for mainstream parties of the left to restore their working-class coalitions with an agenda that speaks to their economic and cultural grievances. Schoen has become a Fox News regular.

Admittedly, this scenario more exactly matches the trajectory of American and British politics than it does the experiences of Israel and South Africa.

As Shenk makes clear, Israel’s once-dominant Labor Party and its political strategists faced a very different challenge. The issue that overwhelmed all others in Israeli politics was the future of the “occupied territories.” As Israeli settlements in the West Bank increased alongside cycles of greater Palestinian resistance, it was Netanyahu’s pro-settler Likud Party that would gain the support of an increasingly right-wing electorate. Hence the efforts of both Labor’s Shimon Peres (advised by Penn and Schoen) and later Ehud Barak (who relied on Greenberg and his partners) to engineer a “peace process” would come to nothing.

As for South Africa, the political challenge for the African National Congress was almost the reverse of Israel’s Labor Party. After decades of oppression, an overwhelmingly black majority was set to take power in 1992. But the price for having an election at all was Mandela’s agreement with the National Party that the ANC would cede control of the economy to the white capitalist elite in the hope that this would encourage economic stability and greater foreign investment.

During the campaign that followed, Mandela engaged Greenberg, who recommended that the ANC campaign on the reassuring promise of “A Better Life for All,” with its complementary slogan of “Jobs, Peace and Freedom.” This was intended to signal the overwhelmingly black party’s commitment to building a biracial coalition. But neither then nor later would a majority of whites vote for the ANC, preferring instead the centre-right Democratic Party advised by Doug Schoen.

The reckoning

Since its publication earlier this year, Shenk’s verdict that “the Left” is more adrift than ever has been amply confirmed. The Democrats have lost control of the White House and both houses of Congress, with the added prospect of an even more entrenched right-wing majority controlling the Supreme Court. While British Labour has been returned to power with a huge parliamentary majority, it is already shaping up as a hollow victory — more the result of the electorate’s sheer exhaustion after years of Tory misrule than any enthusiasm for Keir Starmer’s centrist program.

The ANC still remains in power, but — with only 40 per cent of the popular vote in the 2019 election — it has been obliged to rule in coalition with three other parties. One of these is the conservative, white-dominated Democratic Alliance, which drew on the advice of none other than Stanley Greenberg. Greenberg’s contribution was to encourage the DA to shift a bit leftwards to attract black voters frustrated with South Africa’s listless economy.

On the other hand, the Israeli Labor Party is no more. After securing only four Knesset seats in the last election, it merged this year with its rival Meretz to form a new entity, the Democrats. Today, more than 60 per cent of Israelis identify as right-wing and are overwhelmingly hostile to any political accommodation with the Palestinians. Only 11 per cent see themselves as left of centre.

Beyond the travails of the centre-left in America, Britain, Israel and South Africa, the greater underlying tragedy of the past three decades is that at least two of these self-proclaimed “democracies” are self-destructing as they come under the control of authoritarian right-wing regimes. On the world stage Israel has already become a pariah state in which “the people who most struggle” in what is becoming Greater Israel have no say at all. Meanwhile, under Donald Trump, the United States appears to be on the verge of becoming a rogue state.

So there is real urgency in asking how the social democrats of the centre-left can regroup to meet this perilous moment. Do they in fact need to ask whether the defence of “democracy” must now extend beyond the boundaries of electoral politics and neo-liberal thinking and, if so, how far?

Back to Greenberg’s basics

Shenk believes that the American Democrats, in particular, remain adrift primarily for three interconnected reasons. First, the party is now ruled by a permanent DC-based political class that has become profoundly disconnected from the working class. Second, “the evisceration of organised labour has gutted the institution most responsible for linking blue-collar voters to Democrats.” Third, the absence of any counterweight to the prevailing views of Wall Street and Silicon Valley has “led to policies that lowered deficits, loosened regulations, and reduced trade barriers.” Clinton’s NAFTA agreement still rankles with the white working-class voters in America’s Rust Belt who this year gave Trump his narrow election victory.

So “rather than take on the economic powerbrokers, centre-left governments focused on cultural battles they stood a better chance of winning.” But in 2024 Kamala Harris’s focus on reproductive rights and Trump’s threats to American democracy simply did not resonate with enough of “the people who struggle,” who were far more preoccupied with the high cost of living.

So, in Shenk’s view, it’s time for centre-left parties to go back to basics, starting with “the premise that democracy is a machine for turning the views of ordinary people into government policy.” This will mean combining populist economic messages with “a position on questions like crime and immigration that fits within the broad centre of public opinion — a centre whose death has been conveniently exaggerated by polarisers of the left and right.”

But the real challenge will be to ensure that centre-left politicians make good on these promises. This will mean, above all, “raising living standards in the short term while using the government to build worker power over the long run.” As Shenk acknowledges, “there’s no denying that the odds against this project succeeding are long,” not least because “it runs against the grain of a capitalist economic order that reaches back centuries.”

Is that all there is?

Left Adrift is a short book offering a small window onto a vast subject of global importance. Within his self-defined limits, Shenk offers an absorbing, well written and often entertaining account of how four centre-left parties across three continents over five decades have responded to their loss of working-class support and the increasing polarisation of their electorates. As a conversation-starter about where “lefties” like me might go from here, I’d highly recommend it.

Using Greenberg’s and Schoen’s careers as a way of connecting these far-flung case studies is a brilliant device. What Shenk highlights is how the responses of these consultants’ high-profile clients to their polling, strategies and messaging illuminate the priorities of different leaders and the forces acting on the parties they lead. The ebb and flow of Greenberg’s influence is also especially revealing about how unexpected “events” in an election cycle can quickly undermine any long-term strategic or coalition-building commitments.

Of course, as Shenk acknowledges, the experiences of centre-left parties elsewhere might have suggested alternative approaches to the retention of working-class support and the avoidance of divisive culture wars. For example, while Reagan and Thatcher were dominating American and British politics in the 1980s, the Australian Labor Party held power between 1983 and 1996.

Since then, though, the ALP has succumbed to something of the same drift that has afflicted its American and British counterparts. Working-class support has eroded, thanks partly to a steep decline in trade union membership in the private sector. Cultural polarisation as well as anti-migrant feeling has now increased sufficiently for the Conservative leader Peter Dutton to mount a Trump-style campaign in the run-up to next year’s election, where the high cost of living will be the paramount issue.

Nor are the prospects of the European centre-left looking any brighter. If the German Social Democrats are unable to form a government next February, then every continental EU country — apart from Spain, Malta and Denmark — will be governed either by centre-right coalitions or authoritarian right-wing leaders like Trump’s buddy, Victor Orban.

“It’s capitalism, stupid!”

These transnational trends clearly suggest that there must be some powerful transnational forces at work. While “the capitalist economic order” is the elephant in the room of Shenk’s wide-ranging narrative, he never spells out systematically the many ways in which it exerts its influence both in and well beyond the corridors of power once traipsed by Greenberg and Schoen.

Nor am I about to do so in an already long review. But I do want to highlight two obvious features of contemporary capitalist societies like Australia that underscore the need for a far more radical response from parties of the left than even Shenk suggests.

We live in one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Yet the gap between the working and ruling classes in wealth, income, education, health and many other measures has widened to levels not seen since the 1950s. The lives of workers and their families have grown increasingly precarious as the power of unions has waned and jobs have become more casualised. Meanwhile, the costs of all life’s essentials have risen to the point where access to nutritious food and affordable housing is beyond the reach of many, not least the jobless whose benefits are pegged well below the poverty line. Soaring levels of domestic violence are the collateral damage which have inevitably accompanied these downward spirals.

Nor does the country apparently have enough wealth to underwrite the provision of essential, high-quality social services such as childcare, public education, GP clinics and hospitals, social housing, disability programs and aged care. And some sectors shortsightedly judged to be less essential (like the arts, higher education and other cultural institutions) have deteriorated even further.

So, apart from the increased expenditure of billions of dollars on defence and the forces of law and order, where has all the wealth gone? And likewise what has happened to Labor’s will to tilt the cash nexus in favour of workers and recover a higher portion of the wealth that has flowed overwhelmingly to the institutions and individuals who constitute the ruling class?

Meanwhile, until the ALP summons up greater guile, courage and determination to empower workers and rewrite capital’s social license to operate in Australia, is it any wonder that many otherwise sympathetic to the party are tossing up whether to vote for the Greens, independents or even Peter Dutton?

But at least Dutton is unlikely to emulate Trump’s proposed capitalist takeover of the US government. To date the Don has nominated a Mar-a-Lago mafia of billionaires to run the treasury, commerce, interior and education departments, as well as NASA and the SEC. Not to mention the Orwellian “Department of Government Efficiency,” co-led by the world’s richest person, Elon Musk. Not even the vulgarest of Marxists would have predicted such a blatant coup.

The good news is that there is still time in Australia to create a broad-based movement with the aim of increasing worker power and holding capital to greater account; one that is also linked to a host of campaigns focused on rebuilding our nation’s social, economic and environmental infrastructure. The more that our left-wing parties, unions, climate activists and social justice campaigners talk to one another, the easier it will be for them to identify the common impediments that stand in the way of the changes they all seek. This will include the inevitable pushback and subterfuge that will come from corporate leaders, their lobbyists and the hegemonic media monopolies they control.

One benchmark for the success of this coalition will be the day when the rallying cry of one of the principal parties becomes “It’s capitalism, stupid!” But I don’t think I’ll live long enough to see that.

Back to the future

By way of a postscript you might be interested in what became of Richard Hatcher and the young Democrat I left sprawled in the bushes on that fateful election day.

Hatcher became one of the first black mayors of a major American city, a position he would hold for the next twenty years. During that time he raised millions of dollars in order to change the face of Gary, adding new public housing units, repaving streets and providing regular garbage collections for impoverished inner-city neighbourhoods. He also established the $1 house program that allowed residents to purchase a dwelling if they were able to improve it. This was how he demonstrated his support for Gary’s working-class residents.

But founded as a company town in 1906 — and named after US Steel’s President Elbert H. Gary — the city’s economy nosedived in the 1970s when a third of all its steelworkers were laid off. This accelerated the flight of white families. By 1980 more than 70 per cent of Gary’s residents were black. Four decades later the city’s population had declined from a peak of 200,000 in the early 1960s to just under 70,000 today. With staggering rates of homicide and poverty, it’s a ruined shell of its former self. Neither Gary nor its pioneering black mayor needed reminding of how much its fate depended on the power of those far away few who could make or break their city.

Hatcher also became an outspoken national civil rights champion, hosting the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary before serving as chairman of Jesse Jackson’s Democratic presidential campaign twelve years later. No wonder that in 2008 Barack Obama personally thanked him for letting him stand on his shoulders to support other African Americans running for leadership positions in their communities.

As for myself, Shenk’s Left Adrift — and particularly the career of Stanley Greenberg — reminded me of the person I might have become. A committed liberal Democrat at the beginning of the 1960s, I was part of a coterie of progressive young people whom I encountered as a high-school and later college debater. Some of them, like the star of Gary’s Horace Mann High School debate team, Joseph Stiglitz, would go on to become America’s leading public intellectuals. (Yes, I beat Joe in our only encounter, which only confirms how debating prowess is a very poor predictor of future career success. Just ask Matt Gaetz.)

My Northwestern debate partner, Lee Huebner, was then a liberal Republican (now an extinct species) who worked as a Nixon speechwriter before abandoning a career in politics to become the publisher of the International Herald Tribune and later a journalism professor. And then there was my leading rival on the university debating circuit, Georgetown Uni’s Bob Shrum, a lifelong Democratic political consultant who eventually joined forces with none other than Stanley Greenberg.

Unlike those distinguished folk, I took the road less travelled, abandoning the Democrats, liberalism and the US to become in the 1970s a Marxist writer and far-left activist in Britain. By the time I turned up in Gary to support Hatcher I had already shed most of my youthful idealism, having participated in the March on Montgomery and some of the first Vietnam teach-ins, as well as studying more deeply the origins, growth and impact of American imperialism. My political re-education then accelerated when I went to England in May 1968 to meet the British left-wing scientists of the 1930s, who were the subject of my Harvard PhD thesis. The rest, as they say, is history.

Now more than half a century later, I am not so much politically adrift as more open-minded about what kinds of interventions might lead to major improvements in the lives of “ordinary people.” I also now have far greater empathy and admiration for the past and present contributions of all those mentioned in my review, especially Greenberg, Hatcher and Shenk (but perhaps not Doug Schoen). Meanwhile, I’ll do what I can to support others better placed than myself to hold both Labor and the ruling class to better account. •

Left Adrift: What Happened to Liberal Politics

By Timothy Shenk | Columbia Global Reports | US$18 | 264 pages