This is the budget business wanted — at least, the businesses that are assured of survival and are looking for growth. Whether it is the right budget to get jobs and the economy back to where they were before we ever heard of Covid-19 remains to be seen.

It has echoes of Donald Trump. Scott Morrison and his lieutenants Josh Frydenberg and Mathias Cormann have rejected the advice of economists on the best way to recharge the economy, and focused instead on trying to recharge it with support to key Liberal Party constituencies: business and middle to upper-middle income earners.

Say what you like about Scott Morrison, he is never short of confidence. And confidence is what this budget sets out to create — above all, where it is most lacking at the moment, in business hiring and investment.

The first economic support package in March targeted households, maintaining jobs and incomes through JobKeeper and the enhanced JobSeeker payment. Our disposable incomes shot up at their fastest pace for a decade, but that didn’t stop us slashing our spending. Net household savings leapt $42 billion in a quarter, to its highest level in almost half a century.

This time the budget boys are focusing on stimulating business and re-establishing the Liberals’ brand as the party of lower taxation. Sure, there is also a lot of new spending, including some in surprising and very welcome areas, such as scientific research, home care packages for the aged, mental health services and small-scale road upgrades throughout the land. But the big bickies, more than $50 billion over the next four years, are in tax cuts.

The six biggest budget initiatives, in order of estimated cost, are:

• A huge investment incentive for business, allowing it to write off the cost of investment immediately against tax rather than having to claim it gradually through depreciation. This is estimated to cost $31 billion over the next three years, and to lead to a strong rebound in business investment in 2021–22.

• Bringing forward the stage two cuts to income tax rates by two years, so they take effect retrospectively from 1 July this year. That is estimated to cost $23.8 billion in the next two years.

• As announced in August, the rules for businesses to be eligible to access JobKeeper have been loosened to take account of Victoria’s return into lockdown (where, as I warned, the extreme thresholds set by the Andrews government mean it could be trapped for quite a while). That is estimated to cost an extra $15.6 billion, taking the full cost of JobSeeker from the outset to $101.3 billion before it expires at the end of March.

• Bringing forward an estimated $6.7 billion of investment in transport infrastructure into the next four years. Despite the spin that these would be “shovel-ready” projects, almost two-thirds of the spending is slotted into the latter two years.

• Allowing business to write off tax losses from earlier years over the next two years, at an estimated cost to the budget of $5.4 billion.

• Offering a year-long wage subsidy (or hiring credit) of up to $200 a week to encourage businesses to take on unemployed workers aged between sixteen and thirty-five — the group that now has by far the highest rate of unemployment and underemployment. Treasury estimates the take-up will be high enough to cost $4 billion.

There are a lot of other new measures in the budget, mostly good, but these are the big ones. And you can see that the focus is on getting business to hire and invest over the next two years, on using tax cuts (or cost cuts) to get firms and consumers to go out and spend, and on stimulus in the traditional blokey format of building new road and rail projects.

The focus on short-term incentives is a cunning feature of the design. What these six measures have in common, apart from being big, is that they are also temporary. In some cases, more than that: allowing businesses to write off their new investments and old tax losses sooner means they will be unable to claim them in future years, boosting budget repair in the longer term.

Even on these estimates, recovery would still be slow. While forecasting anything right now is sheer guesswork, Treasury’s best estimate is that business investment this financial year, excluding the mining sector, will still decline by 14.5 per cent, before lifting 7.5 per cent in 2021–22 as the tax-driven projects kick in. Even with the economy rebounding by 4.75 per cent in 2021–22 (which sounds optimistic), it forecasts unemployment will still be 6.5 per cent in mid 2022. A rapid slump followed by a slow climb out.

It was the budget business groups wanted, but not the one economists wanted. I don’t know what Treasury was proposing, but it says something about Morrison and his government that very little proposed by economists outside the official family made its way into the budget.

A good sample of the outsiders’ views was a survey of forty-nine leading economists published last week in the Conversation. The Economic Society drew up a list of thirteen policy options and asked each economist to choose the four that would be most effective in bang for buck to support the recovery. The top six items they selected were:

• Investing in social housing (60 per cent)

• Permanently lifting JobSeeker (51 per cent)

• Increasing funding for education and training (45 per cent)

• Investing in infrastructure (41 per cent)

• Wage subsidies or hiring bonuses (35 per cent)

• Funding high-quality aged care (31 per cent).

Of those, only infrastructure investment and wage subsidies were in the government’s top six list, although one could add a third item: education and training. The budget measures collectively included $1.2 billion in wage subsidies for apprenticeship training and a most welcome $3.4 billion in new support for research — in universities, the CSIRO and industry — with the government finally abandoning its long campaign to cut tax breaks for R&D.

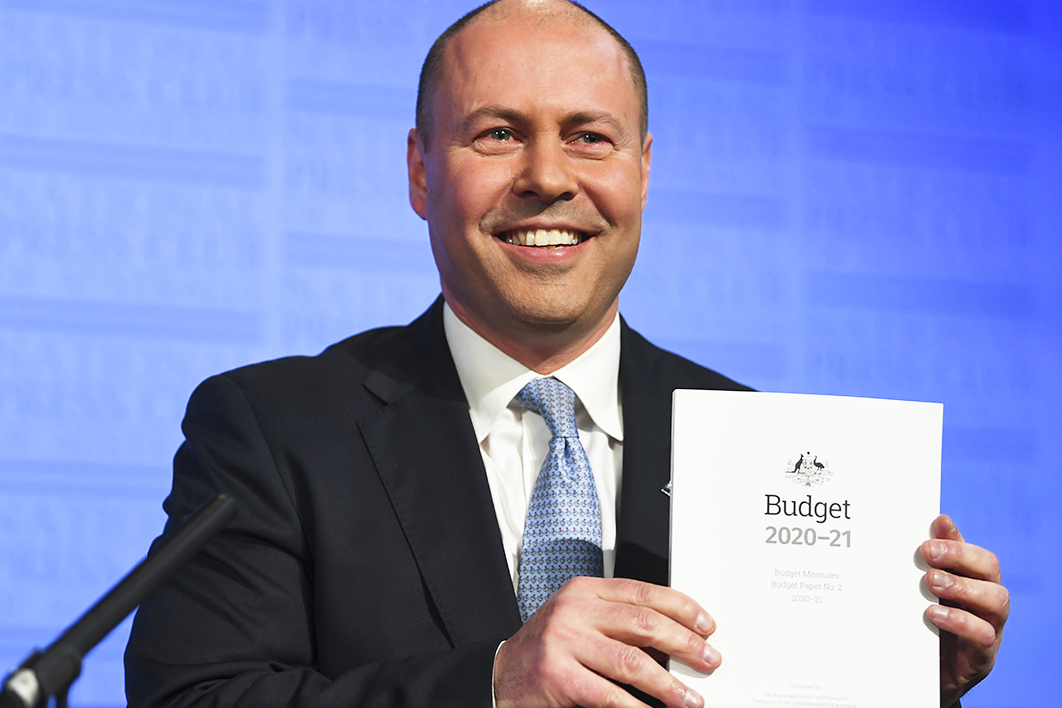

Josh Frydenberg says two other measures in the economists’ top six will be dealt with in coming months. His focus in this budget was on measures that are “targeted, temporary and proportionate.” Presumably he felt it would confuse the public if today’s big news also included the decision to permanently lift JobSeeker payments. There is no other reason that makes sense for excluding it from the budget.

The budget papers note that the government has chosen to hold back the announcement of an unusually large $6.4 billion of additional spending over the next four years, offset by $205 million of additional tax revenue. One might speculate that the decision to raise JobSeeker has already been made.

On aged care, the government says it will await the final report of the royal commission before undertaking a major funding overhaul. For now, it has promised to lift the quota of home care packages by 23,000 — which would cater for barely 20 per cent of those on the waiting list — and meet the commission’s proposals for immediate action, as aged care minister Richard Colbeck announced last week.

But why not social housing?? The budget papers report that housing investment plunged 8.8 per cent in 2019–20 and is expected to sink by a further 11 per cent this financial year before rebounding in 2021–22. When private housing demand plunges, no stimulus measure makes more sense than a one-off boost to social housing, as the Rudd government showed so successfully in 2009–10. It maintains skills and employment in an industry with dense links to the rest of the economy.

Yet all the Morrison government has come up with is its HomeBuilder package, so far a fizzer, and an offer to lend another $1 billion for social housing on concessional terms. It has carefully avoided the public housing solution, even though it works, and instead sought private sector alternatives it could badge as its own solution.

There are too many places in the budget where ideological correctness has been top priority rather than maximising bang for buck. Tax cuts in the past have proved a slow road to boosting spending, and the more so when they are targeted at people in the top third of the income range, as these ones are. Greg Jericho in the Guardian has cut through the government’s spin effectively. All I can add here is that if your prime minister insists on telling you that you’re better off getting $20 a week than $50 a week, don’t hire him as your financial adviser.

The wage subsidies for young unemployed workers were better targeted: shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers’s complaint that they exclude 928,000 other unemployed workers ignores the ugly fact that the young are bearing the brunt of the lockdowns. Economist Callam Pickering, of the Indeed Hiring Lab, notes that one in three young workers are either unemployed or underemployed.

It’s disappointing that the budget has failed to seize on other good ideas from the experts. One of the policy discoveries of this recession has been the value of handing consumers vouchers — where you can specify how and by when they must be spent — rather than cash, which people can save indefinitely. Tasmania, South Australia and the Northern Territory have all done this in some form, yet this budget offers nothing of the kind.

It’s even more surprising when the worst impact of this recession has been concentrated in a handful of industries: eating out, accommodation, tourism, entertainment and contracted services. If you want to target your stimulus, vouchers are an unbeatable way to do it.

The budget also failed to deliver a creative stimulus package aimed at women, who are bearing more than their share of job losses. The show bag of small things it markets as its “Second Women’s Economic Security Package” is an embarrassment.

This budget offers the right sort of program for blokes: it plans to spend $2 billion throughout Australia in the next two years on the construction of small road safety improvements. What it needed was to offer similar programs — temporary, targeted and proportionate — to upgrade our social capital.

The Grattan Institute has suggested hiring unemployed teachers (of whom there are surprisingly many) to work one on one with kids who are struggling with school. I’m sure the royal commission wouldn’t mind if the government jumped the gun by deciding that aged care homes need more staffing resources, now. Programs like these would create a lot of jobs for women — and the long-term rewards could be huge.

But the perfect should not be the enemy of the good: let’s not forget the big picture.

When Covid-19 first struck, there was a brief period of hesitation, but the Morrison government was quick to realise that the old rules had gone. It dumped its obsession with getting the budget back in the black, until then its main selling point. It dumped its long-time brand as being the party of reducing debt, and started building it at an unprecedented rate. It consulted with the unions, with premiers Labor and Liberal, and for a few months — frankly — gave Australia the best leadership it has seen for a long time.

That couldn’t last, and it hasn’t. Scotty from Marketing is back. But even this budget, while not as well targeted as it could be, is about the right scale, and aimed in the right direction. For example, Frydenberg did not try to bring forward the stage three tax cuts, which are class warrior stuff, looking after the rich and ignoring the rest. It’s not a bad budget. It just could be a lot better.

One last point, on population growth. I still love my old paper, the Age, but it ran seriously misleading headlines this morning giving the impression that Australia, and particularly Victoria, is “losing” population. Not so.

In fact the budget papers forecast that over the relevant three years, to 2022, Australia’s population will grow by 384,000, or 1.5 per cent. Victoria’s will grow by 130,000, or 2 per cent. Sure, that is about the same growth as we had each year until now, but you don’t get much immigration with closed borders. It’s a temporary slowdown, and for what it’s worth, Treasury forecasts that by 2023 rapid population growth will be back. Be careful what you wish for. •