Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium: A History of Afghanistan through Clothes, Carpets and the Camera

By Tim Bonyhady | Text Publishing Company | $34.99 | 331 pages

In 1992, returning from a research trip to Israel, I stopped in Singapore for two days to lessen the jet lag. There I made my dream purchase, an “Oriental” rug of spectacular beauty at a price a writer could afford, a kaleidoscope of crimsons and blues that graced our lounge room floor when I got home.

One evening I glanced at the rug and couldn’t believe my eyes. I asked my son to corroborate. “Tanks, warships and helicopters,” he said, having already seen them, as an eleven-year-old would, but until then reluctant to say. We laughed at how I’d been diddled. Little did I realise that what lay at our feet was an item of genuine value.

I tell this story because my ignorance was emblematic of the Western attitudes towards Afghanistan that are the overall theme of Tim Bonyhady’s Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium. Bonyhady, a cultural historian, has fashioned a history through imagery, a refreshing approach to a highly complex and often elusive subject. His exploration of the Western boom in war rugs erupting out of Afghanistan’s conflicts is a prime example of his method.

Afghanistan’s history has been shaped by outsiders’ repeated attempts at conquest, in which their arrogance has combined with the fiercely independent spirit of Afghans to produce failure. First the British, then the Russians and later the Americans foundered there. After twenty years the United States has finally pulled out, dragging us Aussies with them, and the Taliban is poised to take over. The book couldn’t be more timely.

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium spans from the early twentieth century to the September 2001 attack on New York’s twin towers and its aftermath. Apart from its use of various types of imagery as barometers of successive foreign influences and Afghan responses, one other thing distinguishes this book: Bonyhady’s exposure of how that imagery has been greatly misrepresented in foreign media, chiefly because much of it has been shaped by cameras capturing what we foreigners expect to see — a phenomenon that encapsulates for Afghanistan what Edward Said wrote about Orientalism in general.

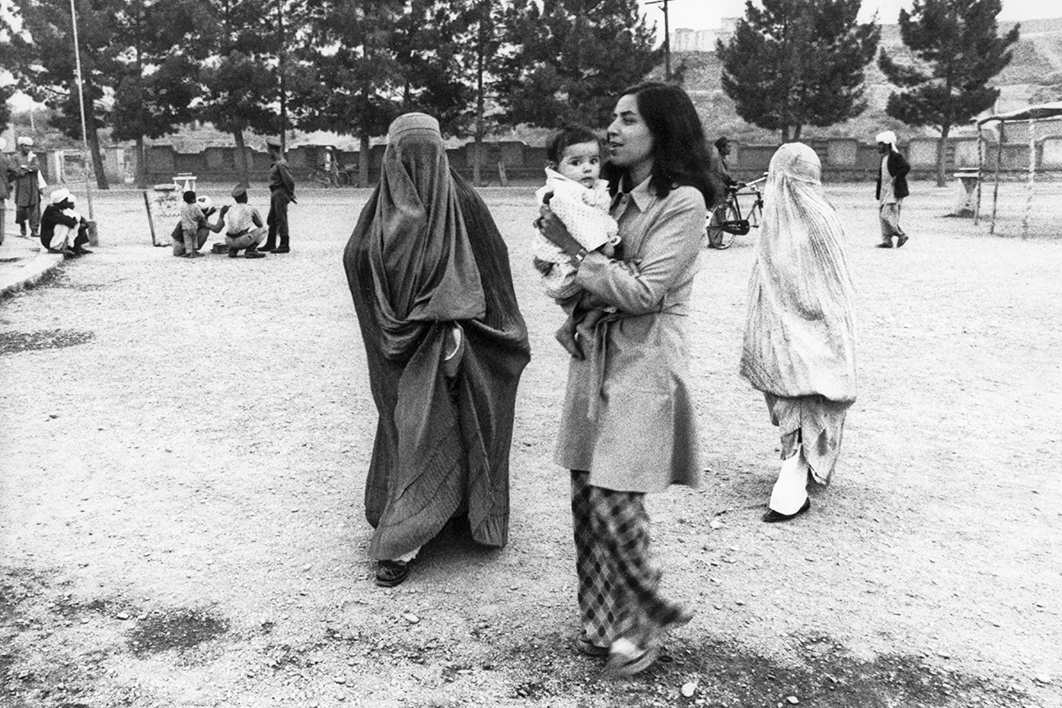

Take women’s dress. You couldn’t find a more politically loaded symbol of Afghanistan’s vicissitudes, from periods of modernisation to those of fundamentalist backlash, complicated by regional and tribal differences, and all of it responding to foreign influence. Add to that the fact that Western perceptions are largely shaped by developments in Kabul, a city that has both welcomed and discouraged the interest of foreign media.

In the 1920s the country’s Queen Soraya made a show of throwing off traditional dress. A famous photograph has her face bared, her hair fashionably bobbed, and her neck and arms exposed in a sleeveless jewelled gown. As a sign of Afghan women’s new freedoms, it appeared in countless overseas outlets. Many upper- and middle-class Kabul women followed suit, throwing off veils and donning short skirts. Girls in the city were being educated, some were going on to employment, and a few ended up in prestigious careers. In 1929, however, their newfound liberties were cut short. A rebellion against Western influence had women back in chadaris (the Afghan burqa) and it wasn’t until 1959 that Western styles took hold again.

It was in that year that Afghanistan’s prime minister staged an “unveiling” at Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium, signalling the government’s return to women’s advancement. For two decades women enjoyed greater freedom in dress and opportunities, at least in the capital, but this was quashed by a new wave of religious fundamentalism triggered by the onset of mullah rule in neighbouring Iran. Then Soviet-backed communists seized power in Kabul, initiating a swing back to wider horizons for women and another relaxation of the dress code. Some women even became celebrated parachutists.

American and Saudi financial support for the mujahideen meanwhile escalated, “transforming Afghanistan,” Bonyhady writes, “into a prime site of the Cold War and of Islamic fundamentalism.” The Soviets hung on until 1989, then leaving a vacuum that enabled a host of tribal warlords to sweep through the country. Two years later the Soviet Union itself collapsed, and by 1994 the Taliban were in charge. Now, twenty-seven years on, history, in that hackneyed phrase, appears to be repeating itself.

This necessarily brief survey doesn’t begin to do justice to the tremendous detail and nuance Bonyhady brings to his subject. The second “afternoon” of the book’s title, for example, was the 1999 public execution in the Ghazi Stadium of a woman named Zarmeena, in striking contrast to women’s ceremonial “unveiling” on the site forty years before. Convicted of murdering her husband, she was clad in a flowing blue chadari when she was executed by Kalashnikov shots to the back of her head. Members of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan filmed the execution with cameras hidden in their chadaris, and the video went viral after one of the RAWA women appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s program.

Zarmeena was most likely innocent, but in such frenzied times any reasonable doubt counted for little in Afghan courts. And Americans, post 9/11, would prove only too eager for evidence of Taliban rigidity. Yet Bonyhady’s portrayal is of an ever-spiralling chaos in which the Taliban themselves were caught. He notes their frequent retraction of edicts in response to popular resistance, and compares them to the warring mujahideens whose bloodlust was far greater. As for their executions, they were fewer than Iran’s or Saudi Arabia’s at the time, or even those by lethal injection in Texas.

While Bonyhady conclusively shows “the heft of the visual,” he also shows how susceptible images are to misrepresentation, not to mention manipulation. He recognises their importance in societies with high levels of illiteracy, yet points to the dangers they hold even in those with literacy rates like our own. Given their central place in his argument, it’s a pity so few images are reproduced in the book.

Still, for an exploration of Afghanistan and its fateful interaction with the West, you couldn’t do better than this book. The wealth and range of its material, combined with its extensive analyses of the status of Afghan women and the roles of posters, photography, television, cinema and pictorial carpets, can make it dense reading, but its map and timeline help with navigation, and I was grateful for the index. The chronological rather than thematic structure can be challenging: its discussion of a single image or artefact — a carpet, say — is set within the various histories of regional carpet weavers, the Western buyers of their carpets and the places they were sold, all in the context of unfolding political developments. A sign of Bonyhady’s breadth, it also means there’s a lot to digest in each chapter.

Finally, if you’re wondering whatever happened to my war rug, all I can say, as a measure of its worth, dear reader, is that it was stolen. •