Thirty years ago this week a group of around forty political, legal and business figures gathered at the Toorak headquarters of the Country Women’s Association for the inaugural seminar of the H.R. Nicholls Society. They were united by their opposition to Australia’s “industrial relations club” – Gerard Henderson’s catch-all term for the cosy alliance of government institutions, employer groups and trade unions that “have a vested interest in the perpetuation of the system.”

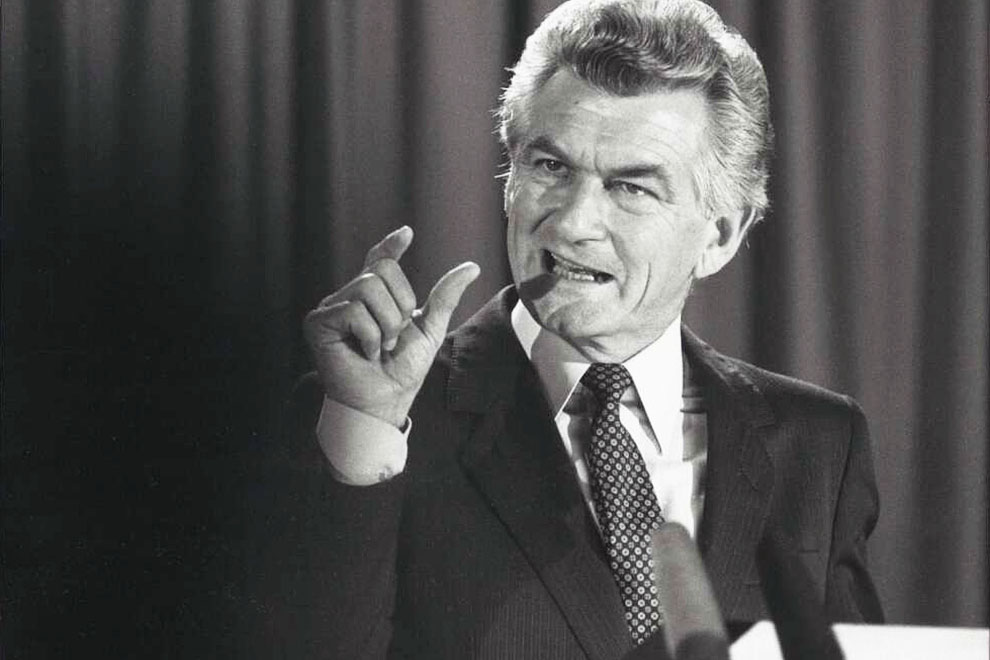

The political climate of the mid 1980s was dominated by prime minister Bob Hawke’s “consensus” style of leadership. Prior to its 1983 election victory the Labor Party had struck a prices and incomes accord with the Australian Council of Trade Unions designed to control inflation and promote employment and economic growth. Shortly after the election, a wider group of political, business, financial and union leaders met at Hawke’s invitation to find ways of confronting the recession.

These developments were discouraging for critics of Australia’s decades-old industrial relations system. And when the government’s review of Australia’s industrial relations laws recommended only minor adjustments, their disappointment only intensified. The time seemed right for a campaign to overhaul the three pillars of Australia’s industrial relations architecture: conciliation and arbitration, centralised wage fixation and the legal privileges of trade unions.

The H.R. Nicholls Society believed that the central premise of the conciliation and arbitration system was fundamentally mistaken. It didn’t accept the notion that a power imbalance exists between employers and employees, nor that they are necessarily in conflict. The two groups, it believed, should be free to bargain harmoniously without the involvement of an umpire.

The Society also opposed centralised wage fixation. Back in 1907, in the belief that the material needs of the male wage-earner and his family should have priority over an employer’s ability to pay, the Conciliation and Arbitration Court had begun setting a basic living wage. But the Society saw labour as a commodity like any other, subject to the same laws of supply and demand. By setting the price of labour with no regard for economic conditions the state was manipulating the market, and damaging the economy in the process.

The other pernicious influence was trade unions. Not only did they use the threat of strikes to force unsustainable wage increases, their corrupt and criminal behaviour also represented a “subversive challenge to the authority of the state,” the Society believed. Though the rhetorical emphasis was on the need to reform trade unions and remove their legal privileges, there is little doubt that the forty people gathered in Toorak that day would have preferred to see them disappear altogether.

So challenging were these ideas to the status quo in 1986 that the H.R. Nicholls Society soon became the focal point of a political furore. Bob Hawke denounced its members as “political troglodytes and economic lunatics” and union official John Halfpenny found himself in court for defamation after referring to it as “the industrial relations branch of the Ku Klux Klan.”

Even some employer groups were alarmed. Brian Powell, head of the manufacturing industry’s peak body, accused the “New Right” radicals of showing “truly fascist tendencies.” All of this hyperbole served only to provide the group with mountains of free publicity. The founders could hardly believe their luck. Consensus, it seemed, was finished.

When John Howard led the Coalition to victory in 1996 the Society had enormous expectations for industrial relations reform, but it was quickly disappointed when the government was forced to water down its Workplace Relations Bill in order to secure its passage through the Senate. In the meantime, though, the government had employed two H.R. Nicholls Society alumni, Paul Houlihan and David Trebeck, to undertake a secret study of industrial relations on the waterfront and develop a plan to confront the militant Maritime Union of Australia.

Many of their radical recommendations were adopted by the government and by Patrick Stevedores, the company that stood to gain the most from smashing the MUA. The subsequent waterfront dispute dominated Australian politics throughout 1998, eventually leading to a legal settlement that, although not a complete victory for either side, weakened the union and led to productivity gains on the docks.

In 2003 the Society urged Howard to become a “truly great prime minister” by taking radical labour market reform to a double dissolution election. Such an enormous risk proved unnecessary, though, once the Coalition had won control of the Senate at the 2004 election and wasted little time in announcing its WorkChoices reforms.

But the purist H.R. Nicholls Society was unimpressed with the exceedingly regulatory approach of the package. “It’s rather like going back to the old Soviet system of command and control,” said president Ray Evans, “where every economic decision has to go to some central authority and get ticked off.”

Evans and his colleagues wanted nothing less than complete deregulation of the labour market. The electorate, on the other hand, thought that WorkChoices already went too far, and punished the Howard government for its ideological overreach by voting it out of office in 2007. Labor’s alternative legislation, the Fair Work Act, was furiously opposed by the Society as a disastrous reregulation of the workplace.

Since returning to power in 2013 the Coalition has been ultra-conscious of the danger of a WorkChoices scare campaign. Even with the weight of the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption behind it, the government remains wary of the kind of radical reform favoured by the Society, apart from its recent attempts to restore the draconian Australian Building and Construction Commission.

The H.R. Nicholls Society also suffered from the retirement of Ray Evans, its founder and driving force, in 2010. Evans’s death in 2014 marked the end of an era for his pioneering form of right-wing political activism. The group’s poorly attended recent conferences are a far cry from what Evans described as the “revivalist” atmosphere of the early years.

In some ways the Society was a victim of its own success. Thanks in no small part to its persistent campaigning, today’s industrial relations landscape is vastly different from that of three decades ago. Views once considered radical are now de rigueur on the right, especially in the cloistered world of the pro-business media and think tanks. Meanwhile, trade union membership has been in steady decline, reducing the urgency of attacking unions in the name of economic progress.

Though it was never particularly satisfied with the industrial relations record of the Howard government, what’s left of the H.R. Nicholls Society might look back on the period as a kind of golden age, the period in which it reached the peak of its influence before old age and the WorkChoices debacle set it on a path of slow decline. Many of its goals remain unachieved, but it undoubtedly contributed to a significant cultural shift, an achievement in itself for such a small clique of political warriors. •