The World Is Beautiful: Photographs from the Collection

National Gallery of Australia until 10 April 2016

The iconic photograph – the image that stands out from the vast supply chain of photographic product for reasons of artistic merit or historical importance, or a combination of the two – has been having rather a rough time of it lately. It is no longer viewed with quite the same reverent eye as it once was. “I could do that,” the time-honoured response to all manner of non-representational art, is now applied routinely to the most representational of creative mediums. With the right software and the right filters, I could do that. We live in a world in which “we are all photographers,” ran a recent Sunday Times review of an exhibition of Annie Leibovitz’s latest portraits, only to take this catchcry of the moment one step further by concluding that “we are all Leibovitzes now.”

When sixteen-year-old Brooklyn Beckham was chosen last month to photograph the new Burberry campaign, the protests from professional photographers came as a brief flurry. Almost anyone can take impressive-looking photographs nowadays, particularly with a little help from the sidelines. While he lamented Burberry’s blatantly commercial decision to employ young Beckham, the professional photographer Jon Gorrigan was philosophical about the likely outcome. “People who are undertrained can get a good result with an Instagram filter,” he remarked in the Guardian. You don’t really have to be a photographer to be a photographer.

Meanwhile, the most surprisingly unsurprising photographs, made with the aid of a repertoire of professionalising tricks, can achieve a new kind of iconic status, if iconic means fetching a million dollars or more. In 2015, the Australian-born photographer Peter Lik – “I just want to see the beautiful side” – reportedly sold his odd-looking image Phantom to a private collector for US$6.5 million, though this record-setting price has been difficult to verify. What hasn’t been hard to confirm is the outrage among all kinds of people who are serious about the practice of photography. Since then, the celebrity photographer Kevin Abosch’s photograph of a potato – Potato #345 (2010) – has been bought for a reported $1 million, once again by a private collector. Potato #345 shows a self-contained and confident-looking potato posed against a pure black background, its knobbly surface lit to lend it a vaguely galactic air. It might be a nice photo, but a chorus of “I could do that” can be heard echoing away in the background.

When a single photograph can be singled out for no obvious reason by a collector prepared to pay a lot of money, there is something exhilaratingly old school about the exhibition currently showing at the National Gallery of Australia. It nails its monochromes to the mast and aims to demonstrate, using about a hundred images drawn from the gallery’s impressive collection, that certain photographs have a certain something that can’t be easily replicated, a certain something that continues to have a powerful impact on generations of viewers. They are images that deserve to be called iconic.

The exhibition title, The World Is Beautiful, might easily be taken as referring to the increasing sentimentalisation of photography, to the exponential growth not only in selfies but also in images of sunsets and waterfalls, or to the routine glamorisation, in genres such as “poverty porn,” of otherwise distressing subject matter. But it is in fact a reference to the influential book of that title, produced in 1928 by Albert Renger-Patzsch, in which the German photographer sought to increase “the joy one takes in an object” and to demonstrate the ability of photography to elicit satisfying patterns of order from the natural and constructed worlds.

Divided into three main parts, “Near,” “Middle Distance” and “Faraway,” according to the distance between the subject and the photographer, this exhibition emphasises the role of the individual behind the camera in making photographic decisions and photographic choices. It “takes the viewer on a journey,” says Shaune Lakin, senior curator of photography at the National Gallery and lead curator of the exhibition, “beginning with extreme close-up views of botanical specimens, and then moving further and further away from the subject until, after one hundred or so photographs, we are looking at images of the open sky and of transcendental phenomena.” There are no found photographs here, no images plucked from anonymous collections discovered on eBay or at suburban garage sales, no unacknowledged and unnamed geniuses. These are iconic photographs by name photographers.

In the photograph used to publicise the exhibition, Robert Doisneau’s Un Regard Oblique (A Sidelong Glance, below) from 1948, we look out of a shop window and see a couple looking in. The implied presence of the photographer, lurking within the shop in order to catch his window-shopping subjects unaware, is just one aspect of the extraordinary complexity of the composition and the fact that the photo constantly gives us more to see. A great deal has been written about this photograph over the years, much of it in the kind of late-twentieth-century-speak that has not survived nearly as well as the photograph itself. But the reason a lot has been written is that there is a lot to see and a lot to say.

Robert Doisneau’s A Sidelong Glance (1948, printed 1990), gelatin silver photograph, 24.1 x 29.5 cm, purchased 1991. National Gallery of Australia

The relationship of the man and woman in the right foreground can be read in multiple ways, their middle-aged formality and their hats (where would photography be without hats?) contrasting with youthful, hatless life going on in the background, all played out within an abundance of oblongs that serve to frame pictures and windows and doorways. The slight tweeness of the title, the man sneaking a sidelong glance at the racy picture to his right while the woman looks at another picture that we can’t see, doesn’t really do justice to the image’s depth of humanity and to its ability, like all good photographs, to suggest life outside as well as inside the frame.

From its very beginnings, photography has divided itself into genres and sub-genres – from capacious categories like portraits and landscapes, or street and studio photography, to more defined areas of focus such as scientific or architectural or even wedding photography. And somewhere alongside all these categories, occupying a kind of parallel dimension, sits avant-garde or experimental photography. The World Is Beautiful draws its selected images from many of these categories. The exhibition includes several of the many precursors of Abosch’s potato, for example, chosen from the long historical line of photographic close-ups of vegetables and flowers and plants. Renger-Patzsch himself, the source of the exhibition title, is represented by two images, one of them of Sempervivum Percarneum, a genus known commonly and unromantically as “houseleek,” or rather more romantically as “liveforever.” This image has a cool, scientific beauty, but it would be a confident observer indeed who, without the benefit of any other information, could look at Renger-Patzsch’s leek and Abosch’s potato side by side and pick the icon. Knowing the date makes a difference – 1928 for the Renger-Patzsch image, 2010 for the Abosch. Getting in early is important – which is only to say that the stature and standing of the image comes not only from the image itself but also from its place in the development of photography.

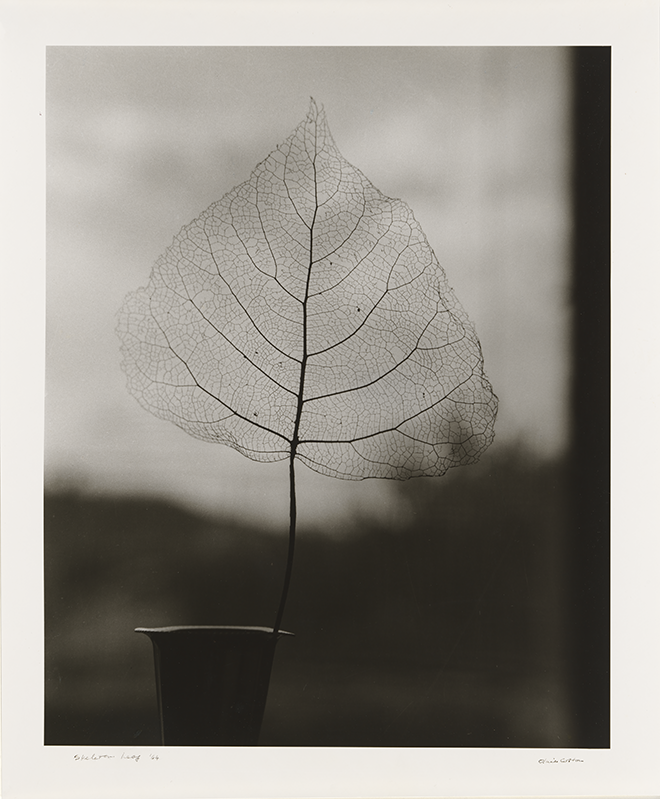

The images grouped under the heading “Near” demonstrate the capacity of the close-up to both unsettle and enlighten the viewer, while at the same time evoking the person behind the camera. That sense of an intelligence behind the image can be felt strongly in the photograph Skeleton Leaf by Olive Cotton (below), made in 1964 in Cotton’s home near Cowra in New South Wales. The leaf, its pulp stripped away to reveal the skeleton, has been carefully positioned, with the natural world blurred but visible through the window in the background. The image is a pleasing combination of the scientific and the pictorial, but most striking of all is how the leaf has been prepared and then photographed in such a way as to imitate the tree from which it came.

Olive Cotton’s Skeleton Leaf (1964), gelatin silver photograph, 50.4 x 40.8 cm, Purchased 1987. National Gallery of Australia

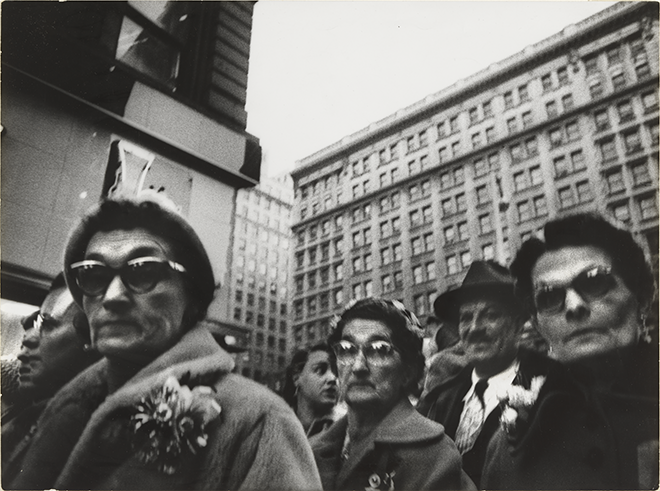

This fascination with pattern and repetition, characteristic of so much of Cotton’s work, is also characteristic of many of the photographs in the exhibition. It can be seen to startling effect in Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Lucia at the Breakfast Table from 1926, with its elaborate arrangement of crosses and circles and shadows, or in one of the images displayed in the “Middle Distance” category, Christmas Shoppers, Near Macy’s, New York (1954, below), by the great William Klein, with its repeat motifs of window frames and spectacle frames and collars and corsages, to say nothing of the splendid hats worn by the shoppers of the title.

William Klein’s Christmas Shoppers, Near Macy’s, New York (1954), gelatin silver photograph, 29.7 x 40 cm, purchased 1993.

National Gallery of Australia

The patterns in Cotton’s and Klein’s images speak to the viewer without the need for explication and explanation. In the case of Moholy-Nagy’s breakfast table or the French artist and photographer Annette Messager’s Mes Voeux (My Vows), made in 1989, it does help to know rather more than the image alone is able to tell us. With Lucia and the Breakfast Table, some knowledge of the “grammar” of the art movement Suprematism and the symbolism of its various shapes, while not exactly essential, will add an extra dimension. The work by Messager, however – a photograph of an installation that is in turn made up largely of photographic fragments depicting body parts – will not rise very far on the impact scale without resort to the gallery’s explanatory notes: “The bodily fragments in Mes Voeux are intended to recall ex-votos – objects, often in the shape of limbs or torsos, left as offerings to saints in fulfilment of a vow or in gratitude for recovery from an illness or injury – that Messager encountered as a young woman in southern European churches.” It is, in other words, a photograph of an icon, but the kind of over-contrivance involved in producing it does not necessarily make for an iconic photograph.

Messager’s is one of the relatively few images in the exhibition to deploy colour. When it comes to achieving iconic status, monochrome rules. Even today, when colour is pretty much universal in vernacular photography and almost universal in art more generally, there is nothing quite like black-and-white for conveying seriousness and weight. Monochrome emphasises pattern, and seeing these photographs together, with each photographer represented by only one or perhaps two images, brings home the extent to which so many great photographs derive their force from the kind of visual pattern and counterpoint that black-and-white so effortlessly underpins. Colours, on the other hand, are naturally assertive, a quality recognised by that most influential of colour photographers, William Eggleston.

In Eggleston’s Greenwood, Mississippi (1973), sometimes known as The Red Room, colour and pattern fight it out – it is an unrelaxing image. Eggleston deliberately tackles the most competitive colour of all, red (a colour that is “at war with all the other colours,” he once remarked in an interview), using a dye-transfer process to capture the creepily rich red of a ceiling criss-crossed by rather dangerous-looking wires. The white wires and the ceiling’s coving (painted partly black and partly white) struggle to impose a pattern on all that redness. In Eggleston’s “iconic image,” as it is often described, black-and-white is no match for red.

The exhibition’s emphasis on the physical position of the photographer – close to the subject, or a little or a long way away – highlights how important stance is to the way we see the photograph. Close-ups, for instance, draw us in – we know that what we are looking at is only part of a whole, but at the same time we are led to take the part for the whole. Eggleston’s image of the garishly coloured ceiling is a clear example, its alternative titles suggesting something larger and more comprehensive than what we actually see – a town, “Greenwood, Mississippi,” or simply a “red room.” In fact, what we do see is a mere fragment of these larger things. But the strength of the image lies not in its representation of these larger things but in its status as a subject, a close-up, worthy of attention in its own right.

Something happens, though, when the photographer steps back. As the exhibition notes have it, the “further away we move from a subject, the more it and its story open up to us.” Photographs shot from the “middle distance” have a way of encouraging the viewer to look for stories both within and beyond the frame. As the selection of images makes clear, this is a particular characteristic of the golden age of American street photography from the fifties, sixties and seventies, where the viewer is quite deliberately led to look outside the photograph’s rectangular border.

In Helen Levitt’s wonderful image from 1972, for example, titled simply New York (below), of children playing on a New York street, a young boy gazes off beyond the left-hand edge of the frame, his eye following along the line of his pointing elbow. In another famous and, yes, “iconic” New York image, Garry Winogrand’s World’s Fair, New York (1964), a row of people sit on a long bench. The man on the right is cut in half, suggesting that the bench, with people sitting on it, extends forever. “As always in Winogrand,” says Geoff Dyer in The Ongoing Moment (2005), “there is a sense of other photos going on elsewhere.” In both the Levitt and the Winogrand images, one in colour and one in monochrome, the human subjects manage to appear both randomly positioned and posed in a pattern, implying a repeating motif that extends further than we can see.

Helen Levitt’s New York (1972), dye-transfer colour photograph, 23.9 x 36.2 cm, purchased 1984. National Gallery of Australia © Film Documents LLC

When it comes to the final category of photographs, long shots, the rationale underpinning the three divisions within the exhibition seems rather to fall apart. “Faraway” is taken here to mean not only the distance between the subject and the photographer but also the geographical remoteness and unknowability of the subject. Photographs taken at a distance, or of subjects that are remote or inaccessible, may well have the “capacity to make faraway places accessible to us,” to quote the exhibition notes, but that is not the overall effect of the images on display. Instead they tend to emphasise the monumentality, the inherent drama and the essential strangeness of their subjects. They are the kinds of characteristics that can, in the case of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Radio City Music Hall (1978), for example, or Trent Parke’s powerful image of technology meeting the outback, A Rally Car Leaves a Trail of Dust (2003), be reinforced by the use of long exposures, resulting in images that lead us to see differently.

The World Is Beautiful is predominantly and unabashedly an exhibition of individual “great photographs” at a time when the so-called democratisation of photography has made many people sceptical of photographic greatness, and particularly the greatness of the individual image. There is much more emphasis now on the cumulative impact of photography, on the way in which a set or collection of photographs, whether by a named or an unnamed photographer or group of photographers, can provide insight into individual lives or political events or simply into aspects of the way we live now. The contemporary prevalence of what might be called “project” photography, in which the photographer pursues a theme across multiple images, invites the viewer to respond to the interconnectedness of collections rather than to an individual, standout photograph. But the works on display in The World Is Beautiful, drawn from the National Gallery’s impressive collection, make a powerful case for the continuing relevance of the iconic image, the one that among all the others really does deserve to stand out. •