Indo-Pacific leaders have gathered in Malaysia and South Korea this week to gauge how the power game is going. The ceremony couldn’t conceal the apprehension, even fear.

Power-balance calculations are a relative judgement about nations on the up, nations falling back, and what happens next. Summits are where leaders put a face to the balance. The problem of the age is that Asia’s summits are less a concert of powers than a concert of uncertainties.

In Kuala Lumpur, the ASEAN leaders’ meetings and the East Asia Summit expressed the great achievement of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations — the creation of a region that has grown from ten to eleven nations now that Timor-Leste has completed its fourteen-year journey to membership. The young country joins the association as the equal of its former master, Indonesia; this is region-creation that overcomes history to embrace geography.

ASEAN’s feat has been to make war between its members seem implausible. But the stability of that mutual assurance took a hit in July when Cambodia and Thailand fought a five-day battle on their disputed border, killing at least forty-eight people and displacing 300,000.

With hefty help from the United States, ASEAN has nudged a ceasefire deal into a framework agreement. On Sunday, Cambodia and Thailand signed a declaration pledging military de-escalation and the removal of heavy weapons from the border, all to be monitored by ASEAN observers.

The concert-of-uncertainties problem for ASEAN is that it has not been able to use the Southeast Asian model to shape the Indo-Pacific future.

Malaysia this week was commemorating the first East Asia Summit, held in Kuala Lumpur twenty years ago. My memory of that 2005 summit is its optimistic mood and sense of possibilities: the Asia-Pacific could link economic dynamism to new structures for peace. (The shift from Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific happened the next decade.)

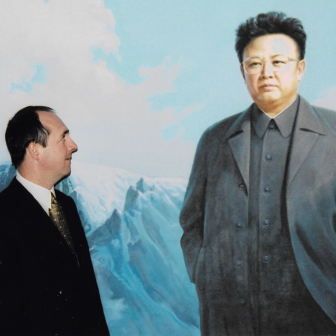

The TV grab expressing that hopeful spirit showed Australian foreign minister Alexander Downer walking into a meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers and taking Australia’s seat at the EAS by signing ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation. The broad grin Downer flashed at our camera expressed personal satisfaction and national achievement. Australia was in! We had a foundation geopolitical seat at the EAS to match our geoeconomic seat in APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation). Australia’s vision of itself as a natural part of “the region” had reached the summits.

My recollection of the first APEC summit in Seattle in 1993 echoes the optimism of Kuala Lumpur in 2005. In Seattle the cold war was dead and the Asia-Pacific future looked rich and peaceful. It was the coldest summit I ever covered. The sleet and snow arrived the day after the first APEC leaders’ communique. Summits offer great vistas and big speeches, but they can’t change the weather.

The diplomatic weather is also buffeting the latest APEC summit in South Korea, where the grouping suffers the same chills as the EAS. The geoeconomic optimism of the Asia-Pacific has been replaced by the geopolitical competition of the Indo-Pacific. The “Cooperation” bit in APEC’s name is embattled; better to render that “C” as “Competition.” And the “Economic” ambitions of open regionalism are mugged by tariffs, de-risking and decoupling.

One element of this week’s Kuala Lumpur summit is as vital today as it was twenty years ago. The EAS has always been about power, not merely geography. If geography ruled, then China would dominate the EAS. In creating the summit, ASEAN, Japan and South Korea needed to get more balance at the table — so Australia, New Zealand and India became founding members. The door was open for the United States to join in 2011, along with Russia.

The tough terms of today’s power game meant US president Donald Trump attended the ASEAN summit in Malaysia and stayed for the group photo. During his previous four-year term, Trump attended only one of the annual ASEAN summits, in 2017, and left before the photo. A president who doesn’t turn up plays to ASEAN’s fears about a capricious America and what that means for being home alone with China.

Power changes geographic understanding, and regional labels are remade. As one of the great academic ASEANists, Amitav Acharya, explains: the “Far East” was created by imperialists, “Asia” was built by nationalists, the “Asia-Pacific” by economists, “East Asia” by culturalists, and the “Indo-Pacific” by strategists.

Acharya argues that the Asia-Pacific was founded on ASEAN “centrality” but the Indo-Pacific does not centre on ASEAN. He worries that the strategic purposes of the Indo-Pacific could impose so much strain on the culture and identity of ASEAN that the association might disintegrate. Nations come and go, he notes, why not regions? “Will the Indo-Pacific idea sink ASEAN,” he questions, “drowning the very idea of Southeast Asia?”

China rejects the “Indo-Pacific,” seeing it as a dangerous American construct. Beijing doesn’t want its dominance of Asia squeezed and challenged by a two-ocean strategy. ASEAN has cautiously accommodated the Indo-Pacific notion, which Acharya judges has been “aggressively” promoted by Australia, India, Japan and the United States.

As an international relations professor, Acharya has both chronicled and organised the concepts ASEAN uses to understand itself as a region and an association. More than most academics, his language turns up in the speeches of the leaders and their diplomats. Two of Acharya’s most influential ASEAN books are the Quest for Identity: International Relations of Southeast Asia (2000) and its expanded version a decade later, Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order (2014).

Acharya returns to those themes with From Southeast Asia to Indo-Pacific: Culture, Identity and the Return to Geopolitics. He again makes the case that ASEAN’s glory is that a group of smaller and weaker players used their smarts to influence the behaviour of the giants:

ASEAN is an anomaly in the universe of great power politics. Not only has it survived, but it has contributed significantly to conflict reduction and management in Southeast Asia and has served as the main anchor of regional cooperation involving all the major powers of Asia and indeed the world. As a result, Southeast Asia is the only region in known history where the strong live in the world of the weak, and the weak lead the strong. ASEAN’s record has been a mixed one, but its existence, survival and purpose turns traditional realism on its head.

But the strong are taking less notice of the weak. Acharya describes a region in crisis and asks, “Will ASEAN survive great power rivalry?” America and China have “moved from being reluctant partners to outright rivals” and a new cold war looms.

The previous era of great power rivalry — the Cold War from the 1950s to 1990s — made the rise of Southeast Asia possible, Acharya writes, by offering an American security umbrella and stimulating common purposes among the 1967 founders of ASEAN (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines). ASEAN’s creation and consolidation was given an economic base by Japanese and US investment as rapid economic growth created domestic and regional stability.

Today’s geopolitical realities are different. China has replaced Japan as Asia’s top economy and China has increased its military lead over all other Asian nations:

Unlike Japan, which embraced its defeat in World War II and became a benign power, China still harbours grievances against Western and Asian powers, including Japan, owing to its mistreatment pre-dating World War II. Where Japan was a provider of investment to Southeast Asia, China has diverted them from it. While Japan has no territorial disputes with Southeast Asian states, China has staked claims to nearly all of the South China Sea, including areas claimed by five Southeast Asian nations.

ASEAN used to talk of being in the regional driver’s seat. The problem for the association now is just getting its hands on the wheel, much less influencing the speed and direction of travel.

Acharya’s discussion of Donald Trump is based on his first term as president. Trump’s departure from liberal internationalism was not a major worry for Southeast Asia because he “continued an engagement policy towards the region, although with less emotion and energy.” Such sangfroid has suffered with the second coming, with a Trump brandishing tariffs as both threat and punishment. ASEAN suffers Trump’s trade-lash.

Trump’s adoption of the “Indo-Pacific” in his first term relied heavily on the US military presence, Acharya writes, creating “a strategic framework for the US to deal with a wider region encompassing East and Southeast Asia as well as India and the Indian Ocean as a single strategic theatre.”

The Trump experience meant Southeast Asia’s “perceptions of the US as a global power and a regional leader have declined, especially when it comes to geopolitics and strategy.” America’s soft power in Asia suffered because Trump often snubbed ASEAN and was seen as heavy-handed in dealing with traditional allies South Korea and Japan.

Where Trump is mercurial, China is usually steady. A China achieving regional hegemony — whether coercive or relatively benign — would be “bad news for ASEAN,” Acharya judges. Beijing would provide “aid, investment and market access in return for loyalty to China in a manner akin to the old tributary system.”

The “rise of China” is an outdated term, since China has already “arrived” as a great power and potential superpower. Yet Acharya sees little sign that ASEAN “will collectively bandwagon with China.” While China’s military strength has grown, Beijing’s military options haven’t expanded with the same dynamism as its economy. Rather than predict Chinese dominance, Acharya points to the many dilemmas and difficulties China faces in the South China Sea and Southeast Asia:

Any temptation it might harbour for creating a zone of exclusion in the South China Sea or a sphere of influence over Southeast Asia would be met with stiff resistance by the presence not only of the US, but also of India and Japan, along with America’s allies, Singapore and Australia. Some ASEAN members, like Vietnam, are at least capable of raising the costs of Chinese military aggression. Moreover, in committing aggression or sea denial in the South China Sea, China has to consider the consequences for its own shipping through chokepoints where ASEAN navies have power of reconnaissance, detection, and even interdiction, and the Indian Ocean where the US and Indian navies are more active and superior. Unlike the Caribbean’s role for America, geography is not on China’s side in its maritime environment.

Acharya describes a life or death choice facing ASEAN. In one future, the region sinks into oblivion, “subsumed and supplanted by its rising neighbours, China and India, and the escalating rivalry between the US and China.” In the other, ASEAN embraces three forces that will sustain it as “a viable, even vibrant idea.” The conditions he lists for carrying ASEAN into the future are:

• Build regional identity

• Embrace freedom and democracy

• Focus on neutrality, hedging and balancing.

ASEAN must recognise its regional roots, simultaneously embracing “outside influences that enhanced its autonomy, while rejecting those that made it an appendage of the civilisations of India and China.” ASEAN’s “distinctive brand of regionalism” engages with all outside powers without being dominated by any of them.

Fostering democracy doesn’t feature too highly in ASEAN’s history. Often it has been an association of autocrats. Or, as Acharya puts it, “[freedom] has not been Southeast Asia’s strong point. ASEAN’s embrace of human rights and democracy has been far too limited and conditional.”

In a region with regimes spanning democracy, civilian and military dictatorships and monarchy, he writes, “the occasional flowering of democracy has been repeatedly hindered by relapses into authoritarian rule.” Southeast Asian states are not likely to emulate Western-style liberal democracy, but “greater political openness might create longer-term conditions for regional stability.”

In the face of US–China rivalry, Southeast Asia must persist with the dance it knows so well, defined by Acharya as “neutrality, hedging, balancing and preserving ASEAN centrality in regional cooperation.” These are the diplomatic techniques expressed in ASEAN’s eternal mantra to the big powers: “Do not force us to choose!”

The ASEAN model rests on that mantra. The superpowers should woo but always accept answers featuring versions of “perhaps” and “maybe.” The dance needs several partners. The model breaks down if the giants don’t woo but instead demand that their wills be obeyed.

The choices become more pressing. The diplomatic weather worsens, clouding the view from Asia’s summits. The quest for ASEAN centrality confronts the reality that Southeast Asia is now at the centre of a new age of power politics. •

From Southeast Asia to Indo-Pacific: Culture, Identity and the Return to Geopolitics

By Amitav Acharya | Penguin | $37.99 | 252 pages