Quentin Blake, knighted for “services to illustration” in January this year, is probably the most prolific and successful British illustrator of all. The first of his more than 300 books, A Drink of Water, appeared in 1960, and he went on to provide the drawings for such children’s classics as How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen (Russell Hoban, 1976), Arabel’s Raven (originally written for the BBC children’s show Jackanory by Joan Aiken, and published from 1972 in a series of thirteen books), and the Monster series (twenty-four of them) by Ellen Blance and Ann Cook (1973 onwards).

His long collaboration with Roald Dahl is a story in itself, beginning with the picture book The Enormous Crocodile (1978), but really taking off with Blake’s illustrations for The BFG (1982). The fusion of these two talents produced, as one critic has said, “a kind of alchemy.” It says everything about the pairing that when Penguin Books bought out the rights to Dahl’s work and wanted to reissue his novels for children in a uniform edition they asked Blake to redraw all the illustrations, not just for the six he had already done, but also for the six that had previously been illustrated by other artists. (The only Dahl book Penguin didn’t give to Blake was The Minpins, with drawings by Patrick Benson.)

Then there are over thirty-five books by Blake himself, a list that includes Angelo (1970), Mister Magnolia (1980), Clown (1995), Angel Pavement (2005) and, most recently, Daddy Lost His Head (2009). Not to be forgotten are the many commissioned works that Blake drew for publishing houses, such as the series of drawings in the 1960s for the Penguin Classics edition (1962) of the novels of Evelyn Waugh. Journeyman work it might be, but for many readers the definitive image of Brideshead Revisited is Blake’s impromptu line drawing of Charles Ryder, Sebastian Flyte and Aloysius (Sebastian’s teddy bear), relaxing with cigarettes and a bottle of Château Peyraguey, as depicted on the cover of the Penguin edition – a drawing that wrought its magic long before anyone associated the scene with Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews.

Monster and the Toy Sale is a typical and low-key example of what a book illustrated by Blake might offer. Monster takes the little boy out on his bicycle – the child has a seat on the crossbar – to a toyshop sale “to buy something special.” Unfortunately, Monster’s services are required by other people – he directs the traffic when the traffic lights fail, he reunites a tearful lost child with his parents, he acts as an information desk for other visitors to the toyshop sale. The boy and Monster are far too busy to buy anything: they leave the shop empty-handed and disappointed. But on the way home they come across a man selling balloons on the street and they buy one. “Everything came out fine.”

Such a story – with its clear moral certainties, its anti-materialism, its belief in selflessness – is a hymn to goodness. The illustrations and their broad palette pictorialise the theme. The Monster, a lavender-blue gangly figure with huge hands and feet, a snout-like, featureless face, twice as tall as the adults, is not threatening but is still a force to be reckoned with. Physically all-powerful, his strength is important but not paramount. Instead his influence is moral, empathetic and protective. He is a friend, a super-parent, an extension of something within the child. The little boy is a personification of innocence.

The creator of this world is a short, stocky, articulate, round-faced, balding man who plods around in white gym shoes. Roald Dahl has left us with a memorable image: “Here’s old Quent – he’s going out to dinner in his plimsolls.” No one else ever called him “Quent,” Blake says, but he concedes the plimsolls. His gestures are precise, his manner is mild and amiable, his self-possession unflappable. He was born in deep suburban Sidcup in 1932 of middle-class parents. He had a good schooling at the local grammar school, where the husband of his Latin teacher, Alf Jackson, himself a painter and cartoonist, spotted his talent as an artist, and another, Stanley Simmonds, “a proper painter,” encouraged him. He was old enough to experience the second world war as a real event in his life (he was evacuated to the West Country). He did his National Service in the early 1950s, and in 1953 went up to Cambridge to read English at Downing College, where his tutor was F.R. Leavis, a man he found to be baffling, inhibiting and “not a good teacher.”

He was then getting work published in Punch, an activity that seemed “unsavoury” in the face of Leavisian high-mindedness. Still, he liked and valued Cambridge: “I thought if I went to art school I would never go to university, whereas if I did go to university I would still have the option of doing art.” After Cambridge, he undertook part-time study at the Chelsea College of Art and Design, then trained as a teacher at the University of London, and ended up teaching at the Royal College of Art, where he eventually became the head of the illustration department (1978–86). He had published in Punch as early as 1949, but from the 1960s onwards published more and more work as an illustrator. Tom Maschler, at Jonathan Cape, emerges as a key figure, for it was Maschler who fostered Blake’s career and introduced him to the writers with whom he enjoyed such long and fruitful collaborations.

Thirty years ago, in a series of events that sum up the stability at the heart of Blake’s private world, he found a studio he liked in a mansion block in Earls Court where his old teacher Stanley Simmonds already had a flat. He then took a flat himself in the same building, where he could live with John Yeoman, a school friend with whom he had been at Downing. He and Yeoman, who wrote the text for Blake’s first book, still live in that flat, and Blake continues to draw and paint in the same studio.

Blake also spends three months a year in his house in southwest France, near the ocean, but like Edward Ardizzone, a forerunner who drew a very different version of Britain, he is attracted by the shabby seaside towns of the southeast coast of England. He discloses little about his private life, beyond saying that he has never been married and has no children, though he insists that when he draws he tries to identify with the children who will be his readers, “rather than look on them as a benevolent adult.”

“Doing art” – the unpretentious phrase conveys something essential about him and the period in which he flourished, the postwar Britain of the end of the class system (according to the plan, at any rate), the rise of the welfare state, streamed free education, Swinging London, Mini-Minors, Habitat furnishings and airy renovated Victorian terraces, the discovery of Greece, France and Italy, and a new democratised aesthetic sensibility that sought out well-drawn, offbeat, mildly non-conformist books for children, books that celebrated unconventionality and impulsiveness. His popularity derives from an artistic vision that chimed in with (and no doubt shaped) the spirit of the age for middle-class Britain in the years between Harold Macmillan and the election of Margaret Thatcher. Goodbye to all that.

The newly published Quentin Blake: Beyond the Page is a chronicle of the latest phase of Blake’s career, from 2000 to the present day. It is generously furnished with over 300 illustrations, nearly all of them in colour. It is well-designed and beautifully, not to say sumptuously, produced. Partly a résumé of developments in Blake’s career, it has a narrative of sorts, recounting how his drawings have managed to get off the page and find new homes in a series of public venues, a development that Blake values and draws strength from.

Beginning with an invitation from Michael Wilson in 2001 to draw on the walls of the National Gallery (of which Wilson was then Director of Exhibitions), the book shows how Blake’s work began to appear on a wide range of public surfaces: stamps, posters, wallpaper, fabrics, walls, theatre foyers, a development site opposite King’s Cross, library buses in Africa, a psychiatric-care centre, an aged-care centre, a hospital for children in France, a maternity hospital, also in France. Blake offers a commentary which gives a sense of how the appearance of his art in public spaces has exhilarated him and given him a new sense of purpose. Equally interesting are his comments on the technical aspects of enlarging his drawings to the huge sizes needed – in one case the figures had to be as high as a five-storey building.

Blake has confessed that he can’t really draw cars or buildings, that unlike (say) Ronald Searle, with whom comparison is inevitable, he has only a minimal interest in place. Searle’s Paris, for instance, is the kind of thing that is either beyond Blake or doesn’t interest him much. What he draws best is “movement, gesture and atmosphere.” His pictorial world is defined by three things: a freely developed line, the recursion to a certain pose, and an anti-Newtonian attitude to gravity.

The line is scratchy, uninhibited and unpremeditated – improvised, ecstatic, free, anarchic, even manic. It owes much to André François, an indebtedness that Blake has freely acknowledged, saying how taken he was by the way François’s painterly, “not respectful” drawings seemed “improvised on the page.” One might think that such a line is sufficient, it is so alive, but when Blake applies colour – his characteristic vibrant, irregular, watery palette of pinks, blues, yellows, reds, greens, and grey washes, as he has done to the previously black-and-white George’s Marvellous Medicine – it is not merely an addition, but the opening up of a new expressive dimension. The elements of the most characteristic pose in Blake’s work are found in his drawings of Mister Magnolia. Extravagantly dressed, he adopts a bold, upright, self-assertive stance, his feet at ballet position three, arms outstretched, fingers spread wide, meeting the world head-on. Such figures in the Blake universe tend to behave as though the laws of gravity do not apply to them. They climb up high, upon boxes, flowers, trees or buildings, they rollerskate, perform acrobatics, swing on trapezes, dance on tightrope wires. They fly and show no fear of falling. And there is the smile – Mister Magnolia wears a huge grin that loops all the way around his face.

Blake has been accused of being “too cheerful,” and although he could point, with reason, to his illustrations for Voltaire’s Candide or the drawings he did for Michael Rosen’s Sad Book about the early death of a son, the charge is not without foundation. He concedes that his work has no dark side, no “hidden Gothic archive.” But “cheerful” is the wrong word. Blake’s work is innocent.

For an earlier Blake, whom Leavis thought one of the most important English poets, innocence and experience were the “two contrary states of the human soul,” and both were necessary, for “without contraries there is no progression.” If there is a case “against” Quentin Blake it might be framed in this way: that he tries to proceed equipped with only one half of the dialectic, to produce the single-handed handclap. One response might be to say that in Quentin Blake’s art innocence is supplemented by something else: energy. Indeed, his drawings, with their cast of gravity-defying figures, exemplify the Blakean principle of “energy,” which, being “from the body” rather than the mind, is “Eternal Delight.”

“Eternal Delight” – “joyfulness” – might explain why it is so moving to find such drawings in modern sites of medical suffering like clinics. Such a place is a psychiatric facility, the Gordon Mental Health Centre for Adults in Vincent Square, London. Blake’s drawings show fully clothed people – old men and women, mainly – swimming under water in the company of schools of fish. Blake cannot explain their origins, still less what the drawings mean, and he calls their creation “illustration pulled inside out.” They are strange and unaccountable but uplifting.

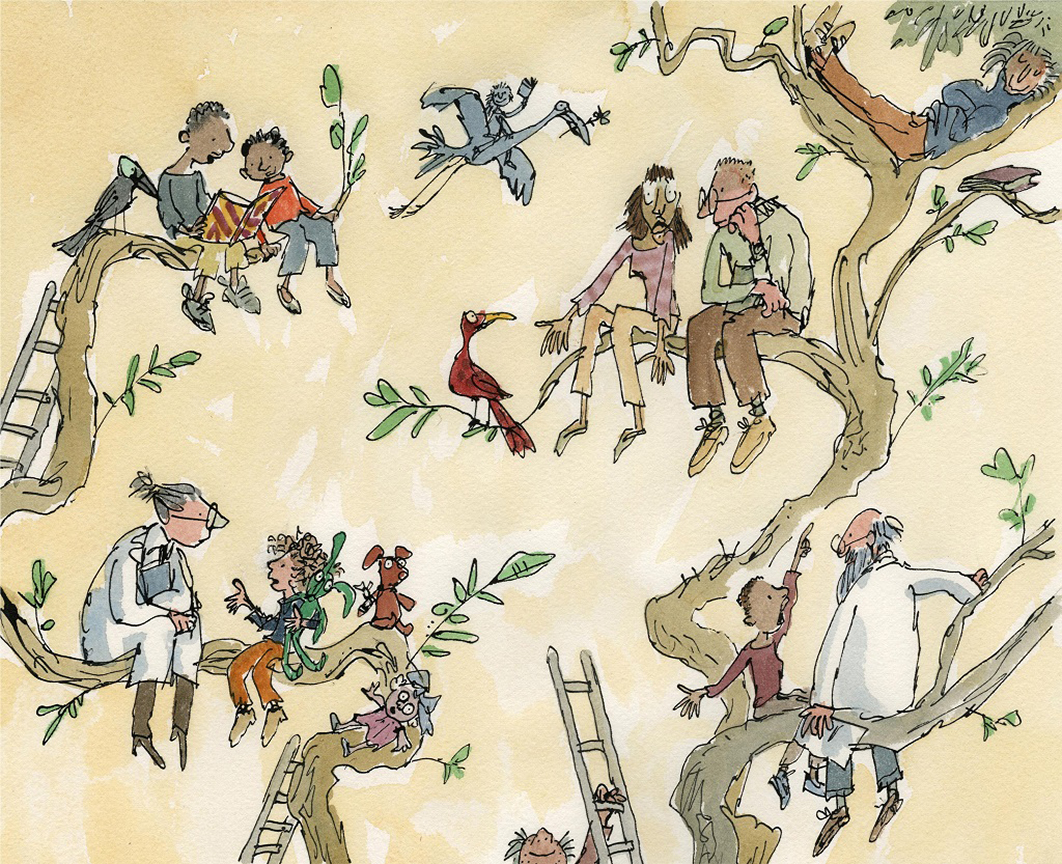

Even more moving are his drawings for the Hôpital Armand-Trousseau in Paris. This is a hospital for children of all ages, including the poorest immigrants from North Africa, who suffer from both physical and psychological ills. Blake’s wonderful murals show children of all sizes and colours, ascending ladders, stepping confidently across wooden bridges with no handrails, leaping from heights to be caught in blankets held out by doctors and parents, consulting physicians perilously, but safely, high in the branches of trees: “in varying states of optimism or” – Blake realistically adds – “despair.”

Drawings like these show the world through the eyes of innocence, a world that is both self-sufficient and self-sustaining, which, one hopes, can return to the suffering children a small but plausible utopianism in a situation of distress and danger. What is good about them is that they can have no conceivable design upon anyone – they cannot be charged with trying to cheer anyone up, for instance, least of all the patients. Their virtue lies in the absence of motive beyond a confidence that such drawings can be made to work in such a setting. But perhaps an additional reason why Blake values as much as he does these works in places of suffering and pain for the old, the sick, the mad, is that those places supply in a happenstance and unexpected way – not as part of a “project,” with the attendant self-serving personal motivations – the missing, complementary half of the Blakean dialectic. •

Beyond the Page

By Quentin Blake | Tate Publishing | $39.95