Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse

By Cassandra Pybus | Allen and Unwin | $32.99 | 336 pages

Cassandra Pybus is a historian whose narrative force is a seduction and balm for any weary reader. In her latest book she gains our trust with a preface that locates her entanglement with both her subject (her generational, and current, home is a place Trucanini* knew) and her object (we must tell the truth of what genocide, exile and dispossession have done to First Nations and all Australians).

In a feat of scholarship unlikely to be repeated for some time, Pybus displays an intimate, lifelong connection with the research material. She is an equal to those she counts as peers and mentors, deserving a place alongside Lyndall Ryan (to whom she dedicates the work), Brian Plomley, Rebe Taylor and Henry Reynolds as someone whose thoughtful, knowledgeable and compassionate words stick to the skin long after the reading is over.

I will revisit this volume often as I learn to see old facts regarding my many-times grandfather Mannalargenna and grandmother Woretemoeteyenner in new ways. And I am grateful for the turn of restorative history towards our countrywoman who, nevertheless, can never be at peace while she is so central to a foundational Australian myth of extinction (ours) and beginnings (not ours).

So why, then, would I hesitate to recommend this book if you, like me, were from trawlwulwuy people of tebrakunna country, now known as Cape Portland, northeast Tasmania? It is so obviously about our kin, ancestors, country and bodies, so obviously concerned to reclaim our magnificent Trucanini by finding “the woman behind the myth,” and it will become a staple in many of our homes, including mine — yet I see little of my people in it.

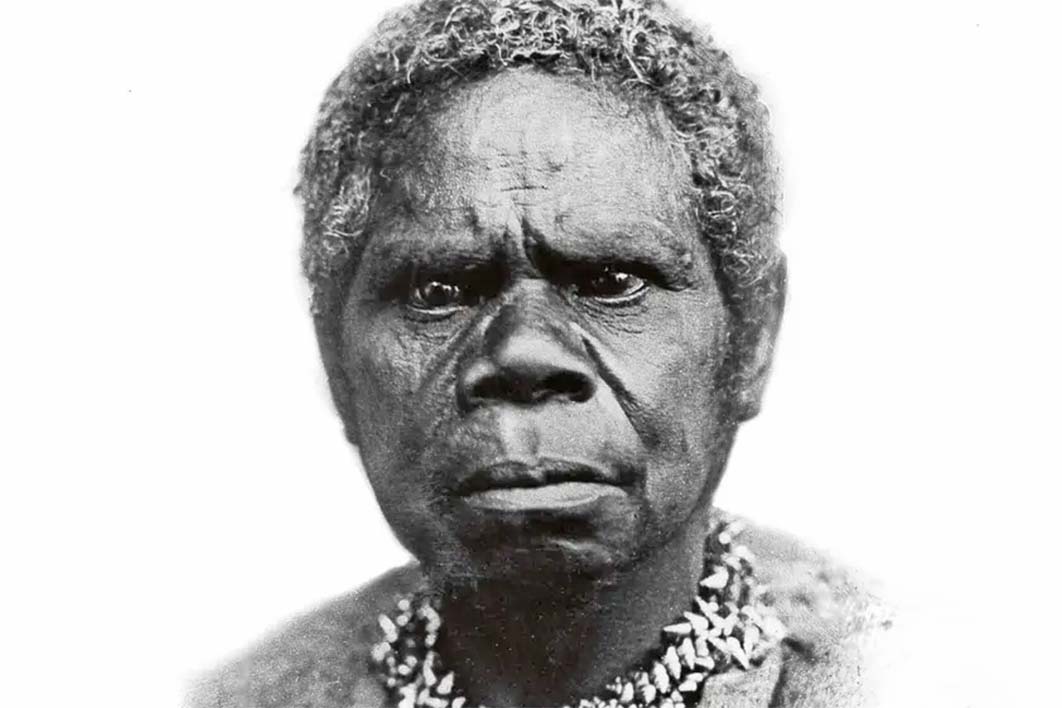

Some of Pybus’s narrative choices are concerning. She interprets Trucanini as “pensive, even sad” in a sculpted bust or “grumpy and uncomfortable” in a photo, when it’s more likely her expressions reflect the lengthy sitting times for those art forms. We have to be careful when we seek more than Trucanini is capable of giving. The same can be said of some of the evidence used — for example, on the renaming of the subject of Thomas Bock’s portrait of Trucanini in the British Museum. To me, the evidence cited — which includes Bock the artist mislabelling his own portrait, and George Robinson, who spent decades with Trucanini, confusing her likeness with another — is too slim to justify the claim that another woman is depicted.

It is also disappointing that the narrative ventures into the exoticised and sexualised disease of syphilis. Pybus is not the only historian to diagnose a syphilitic Trucanini, yet in the same breath she acknowledges the comorbidity of a range of common diseases (which led to a complete immune breakdown for our people) to demonstrate a poverty of health.

Is it likely that syphilis would have gone unnoticed in Trucanini, the woman whose flesh was boiled down by the best anthropologists in the business and whose skeleton was displayed in a museum? Hardly, I would say, given the evidentiary importance of the public display of her remains, and the state’s interest in demonstrating how unworthy our diseased bodies were. Absence of evidence is not evidence of syphilis.

Yet I am more unnerved by the things Pybus takes for granted in framing the research, which produce a kind of soporific that lulls us into complacency and acceptance of the things that harm First Nations. Even while doing the real work of truth-telling, and trying to repair colonising wrongs, this book reproduces tropes, stereotypes and deficits associated with First Nations, especially trawlwulwuy peoples, that permeate Western humanities.

When Pybus reflects on a 1980s Tasmanian museum diorama including Trucanini, describing it as a “melancholic requiem for the disappeared that reeked of regret without responsibility,” I can’t help but feel that strains of this sentiment are reproduced here. Her book is themed around two women — Trucanini and the author — whose stories come together through time and place, yet only one is given life. Trucanini remains a dead black woman, contrasting with the one who is very much alive and able to choose the facts, the narrative style and the story’s start and ending.

Pybus’s story ends with a poignant call for what is right: “to pay attention and give respectful consideration when the original people of this country tell us what is needed.” Trucanini’s story, by contrast, ends again in her death, with not one word of what happened afterwards. That original full stop gave rise to the myths of extinction that our peoples suffered so dreadfully between 1876 and December 2016, when we were acknowledged in the Tasmanian state constitution as traditional owners and First Peoples. Here, it again stifles and mutes her and, in effect, her kin today.

This leaves no sense that our peoples exist beyond her death. It’s hinted at, alluded to, given a sentence here or there, but it is clear that we don’t own this story and have been separated from our own historical labour and sorrow.

The choice to end with Trucanini’s death is also the choice to steer clear of engagement with “what is needed” by us, by people like me, in the complex task of picking up the pieces and gaining our own voice and spaces, and making our own interpretation of our ancestors and kin. This right is absent from Pybus’s towering volume, prompting bittersweet reflections on my own un-belonging in this narrative of my peoples and family.

Yet I unashamedly take pride in this feat of history writing because I belong to Trucanini, not by blood but by kinship and the reciprocity of our women, our Elders, our grandmothers and ancestors here in Tasmania. I do this because I know that the stories of our women, including Trucanini, are still unfolding, and hope for a time, perhaps in my lifetime, when her voice is brought alive with the joy and language and belonging and connection by one of us. Then our precious and dear countrywoman will finally finish the cultural journey home that she is due. •

* Trucanini is the reviewer’s preferred style and spelling, and the trawlwulwuy people’s language and Country are also italicised.