The unsurprising defection of Cory Bernardi from the ranks of the Liberal Party might create an immediate headache for an embattled Malcolm Turnbull, but it is merely the latest eruption of the tensions that have bedevilled Australian conservative parties for more than a century. At their core are questions about the role of a conservative party in Australian society.

The problem has its roots at the end of the nineteenth century, when the rapid growth of the Labor Party catalysed the creation of parties representing town and country capital under the banner of the “anti-Labor parties.” Whatever the various names they subsequently went under, their objective was, and is, to keep Labor away from the levers of power.

The early anti-Labor parties were themselves divided by the big issue of the day – tariffs on imported goods. In Victoria, the Protectionists were in the majority, adopting a form of social liberalism that came to be identified with Australia’s second prime minister, Alfred Deakin; in New South Wales, with the Free Traders in the ascendancy, the social conservatism identified with NSW premier and future prime minister George Reid was dominant. With the settling of the tariff issue and Labor’s continued rise, the two parties buried their considerable differences in 1909 in what became known as the Fusion, giving birth to the first Liberal Party.

It was a marriage of convenience, and there were misgivings aplenty. Several of Deakin’s radical wing declined to come across, with some sitting as independents and others moving to the Labor Party. For their part, many of the old Free Traders resented rubbing shoulders with their erstwhile political and ideological foes. The historical tensions, arising from different political traditions, have persisted to this day, as has the need to find a cause other than simply opposing Labor.

The conservative Free Traders, having lost their one cause in 1905, for a time became the Anti-Socialist Party in their search for relevance. Meanwhile, little of Deakin’s social liberalism was in evidence in the first post-Fusion government, Joseph Cook’s short-lived government of 1913–14, which spent most of its time and energy seeking to undo the work of the previous Labor government.

Any consideration of the philosophical and ideological underpinnings of the anti-Labor parties was put aside when the Labor Party split, first over the issue of conscription during the first world war, and then over economic policy during the Great Depression. In each case, Labor governments fell and the vacuum was filled by pragmatic anti-Labor politicians augmented by Labor renegades.

As long ago as 1930, historian Keith Hancock wrote that while “strong conservative interests” were present in Australia, “they have been persistently baffled and thwarted in their attempts to express themselves in the parliamentary struggle.” This is a proposition with which Senator Bernardi would surely agree.

Only after the implosion of the United Australia Party, the main anti-Labor party and forerunner of the modern Liberal Party, in the 1940s was serious thought given to conservatism and how to frame and market it as a political product. Simple reaction was no longer enough, especially given the popularity of wartime Labor under John Curtin.

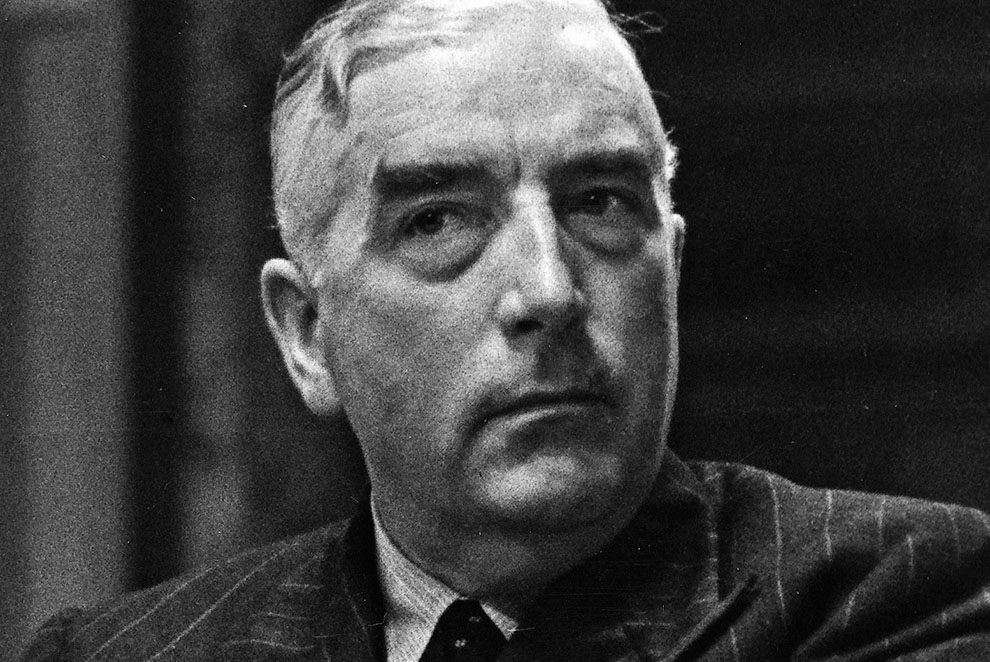

Robert Menzies, UAP prime minister during 1939–41, convened a series of meetings of like-minded groups that culminated in the formation of the Liberal Party in late 1944. Despite suggestions from supporters of the new organisation, Menzies emphatically refused to call it the Conservative Party, arguing that there was “no room in Australia for a party of reaction… [and] no useful place for a policy of negation.” As a later Liberal prime minister, Malcolm Fraser – a man who knew Menzies well – said decades later, Menzies was never a conservative. “He never used the word ‘conservative’ to describe the Liberal Party. He said the party was progressive and forward-looking.”

What Menzies did, and what no anti-Labor leader before him had managed to do, was to construct a powerful narrative involving “the forgotten people,” whom he addressed in a series of radio broadcasts heard in Melbourne and Sydney. He appealed to, and built his policies around, the fears and aspirations of a middle class, managing to persuade them that they were not being listened to: “those people who are constantly in danger of being ground between the upper and the nether millstones of a false class war.” It proved to be an effective counter to Labor’s well-projected image as champion of the working class.

Historian Janet McCalman has written about how Menzies “made Australians feel good about themselves.” Above all, he understood his true constituency: he comprehended the soul of the middle class in a way no other Australian politician had done, reshaping conservative politics to a vision of the future rather than a reactive return to a mythical past.

Malcolm Turnbull’s problem is that he lacks any narrative, compelling or otherwise. His slide in the polls is of such magnitude that the only way he can stave off defeat at the next election, with Labor playing a calculatedly cautious game, is to find a new connection with the electorate and reinvent his government. We have to wonder whether this is remotely possible given his lacklustre front bench and the absence of any discernible latent talent behind it.

In the past, the main anti-Labor parties have seldom been in danger of being outflanked from the right. But the surge of support for One Nation poses just such a threat, and will be tested next month in the state election in Western Australia. What the polls tell us is that burgeoning support for Pauline Hanson’s party is coming at the expense of the Coalition.

The populist route flagged by Bernardi and the right-wing columnists might be the only hope of salvation for the Liberals, and a desperate one at that. It would represent a complete abandonment of principle – but one that has a precedent in Alfred Deakin’s selling out all he had stood for to bring about the merger of the early Liberal Party with the Free Trade conservatives in 1909.

The existential issue for the Liberal Party is whether it retains any vestige of a belief in looking ahead and sharing a constructive vision for the future, as Menzies did when he harnessed national development to social security and aspiration. When the rhetoric of Bernardi and others of his ilk is stripped down, it is nothing less than an attack on the commitment to a just and fair society, which must be one of the objectives of any party that purports to support democratic institutions and processes.

When you look at the language used by Bernardi and supporters like John Roskam of the Institute of Public Affairs, it is clear that they are engaging in dangerous doublethink of the kind that George Orwell warned against seventy years ago. In his polemical book, The Conservative Revolution, Bernardi takes issue with the use of the term progressive by his political opponents, arguing that the agenda with which it is usually associated would lead to “social dissolution, poverty and a sense of loss.”

In a strictly political sense, progressive can only mean a more equitable spread of wealth, income and opportunity, and with these political power; the sense of loss he bemoans can be felt only by those who hitherto enjoyed unearned privilege. Bernardi’s attack on democracy seeks to preserve an unequal social and political hierarchy – the domination of women by men, of coloured people by whites, of the poor by the wealthy, and of the have-nots by the haves. Is this what a refurbished Liberal Party would look like? It is a far cry from Menzies’s boast that his party stood proudly for equality of opportunity.

Bernardi likes to cloak his beliefs in the garb of “common sense.” Roskam, for his part, seeks to recalibrate the political compass. Refusing to concede that Bernardi’s views are out there on the farthest shores, he referred in an ABC interview this week to Bernardi as inhabiting the “centre right” on the political spectrum and Malcolm Turnbull as being “centre,” constantly repeating the term “centre right” in relation not only to Bernardi but also (incredibly) to Hanson as well. His evidence-free theme was that the Liberal Party had veered “too far to the left.”

The parliamentary party is probably better off without the distraction of a Cory Bernardi within its ranks. The big threat from the far right, and from One Nation in particular, will test the qualities of Malcolm Turnbull and his key lieutenants – but the response will also define whether the party of Menzies will retain its democratic principles or capitulate to the insurgents of the lunar populist right. (The populist destruction of the US Republican Party – the party of Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt and Eisenhower – should send a clear warning signal.)

The very real public policy challenges facing all Australian governments –galloping economic inequality; the decline in housing affordability; the devastating effects of scientifically validated climate change; disturbingly high levels of domestic violence; unequal access to education, healthcare and justice; inadequate welfare for the vulnerable and needy; and the disgraceful indicators of Indigenous health and life expectancy – will inevitably be marginalised in any capitulation to the far right. The costs of political expediency could be high indeed. •