In the evenings after dinner, writer Nettie Palmer and her daughter Aileen would often roam the streets of suburban Hawthorn. Sometimes they spoke only in French, at other times only in German. An accomplished linguist, Nettie had studied for an International Diploma of Phonetics in France and Germany in 1910–11 after she completed her arts degree at Melbourne University. Aileen inherited her mother’s love of languages, and the walks began when she was a student at the Presbyterian Ladies’ College in the late 1920s. She went on to major in French and German language and literature at the university, taking French honours in her final year in 1934.

Nettie confided to her diary that she doubted Aileen was getting much “orthodox work” done in her honours year as her energies were devoted to the Communist Party and the anti-war movement. Aileen had joined the CPA at seventeen, in 1932, and was active in the university’s Labour Club, editing the August 1934 issue of the club journal, Proletariat. Like many Australian writers and intellectuals, she was active in protests against the Lyons government’s increasingly strict stance on censorship. It was no accident that the works banned were usually those that promoted left-wing or communist views, even if the official reason was indecency.

Aileen’s political activities were ramped up further when Egon Kisch, the Czech national, Paris-based writer and communist, made his controversial visit to Australia in November as an invitee of the Movement against War and Fascism. After he was barred from disembarking from the Strathaird in Fremantle, it became clear that Kisch was to be prevented from leaving the ship when it sailed into Port Melbourne. Aileen threw herself into helping to organise protest meetings.

In the previous year Vance and Nettie Palmer had moved to a rented cottage at Kalorama in the Dandenongs, east of Melbourne, on account of Nettie’s health, their two daughters staying with their grandmother in town to continue their studies. On a visit to her parents during the August university break, Aileen decided to write her honours thesis — in French, as required — on Marcel Proust. But she only immersed herself in the task after her final university exams were over, and had to fit in a pre-Christmas sales job at Mullens the booksellers. With the thesis due at the end of January 1935, she reluctantly cut back on her involvement in the organising team for the Kisch protests.

At first, Aileen stayed in Carlton with friends, a decision her mother privately thought was not a good one. Nettie was proved right when Aileen arrived with luggage and books at the house in Kalorama a few days later, deciding she might work better there. From then on, the production of the thesis became a Palmer family affair. Nettie read it as Aileen wrote, declaring it to be a “terrific assemblage of Proust & his illuminators.” The fireplace filled up with screwed-up sheets of green paper. Helen, Aileen’s younger sister, started typing long sections of the thesis, while Aileen prepared and corrected the sheets further on.

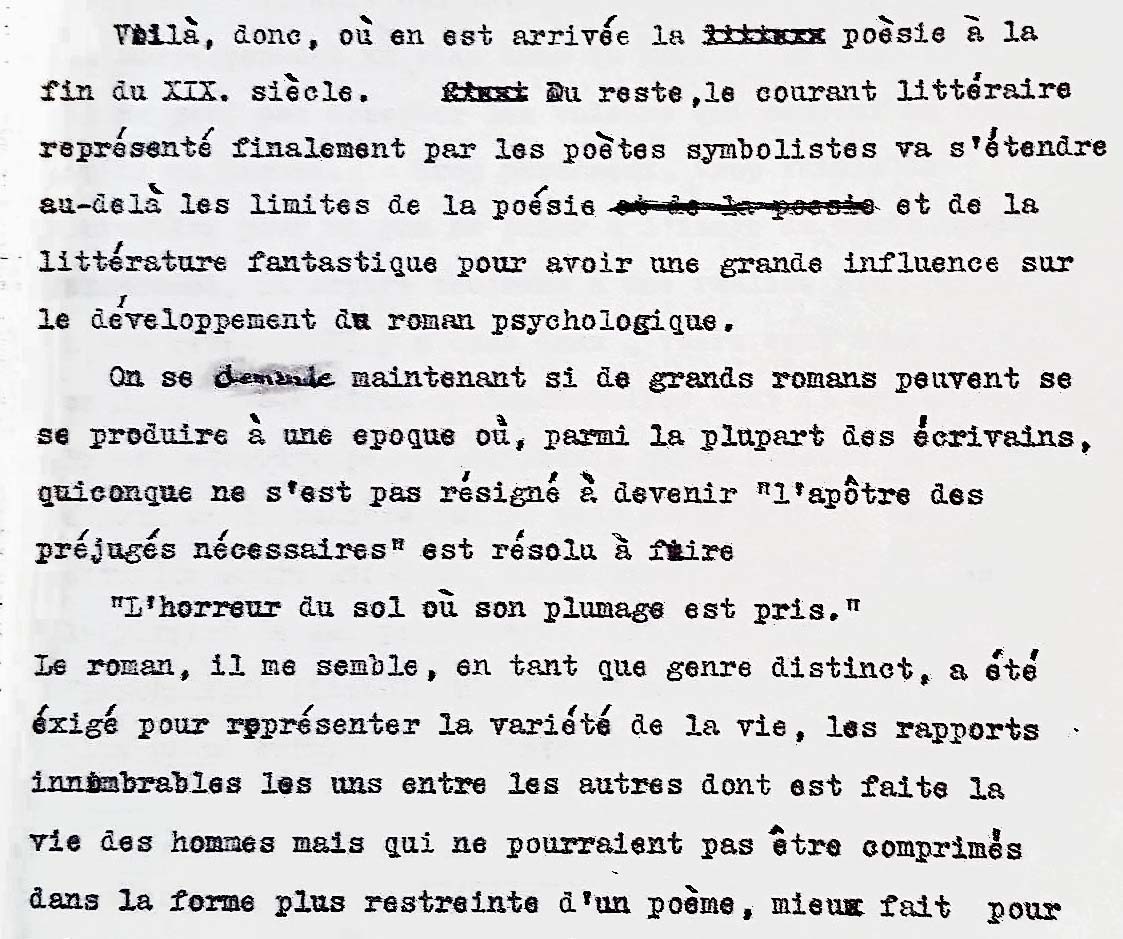

By 25 January, she was writing the conclusion. Vance bound two copies on the 27th, declaring that the carbon copy was more readable as the typewriter ribbon was old and pale. Aileen started rereading and correcting in the afternoon, mainly putting in by hand the French accents that were not available on the typewriter. Helen took over, then Nettie, and the process was finished by midnight. The next day Aileen packed up the copies, each of sixty-nine folio sheets, and took the morning bus to town. “A peculiar calm descended on the house,” Nettie recorded.

A page from Aileen Palmer’s thesis. State Library of Victoria

Aileen finished the hectic month of January 1935 by refusing to go on a camping holiday with her family as she was too busy with committees and gathering names for an anti-censorship petition. Her decision was not popular with her parents and sister, perhaps understandably, after the effort they had all put in to help her get her thesis submitted on time.

But the publication of Aileen’s university results in the newspaper on 22 February helped redeem her in her parents’ eyes, although only after some confusion. She had forgotten her number and assumed in her panic that she was the one with the second – honours. As it turned out, through Helen’s more practical interpretation of the coded list in the paper, Aileen had been awarded first-class honours in French language and literature: “it seems,” Nettie wrote, “by reason of her astonishingly original thesis.”

After completing her university studies, Aileen travelled with her parents to England where, a year later, she combined her political interests and her knowledge of languages by volunteering as secretary and interpreter in the first British Medical Aid unit to go to Spain to support the Republican government. A decade later, after two years on the frontlines in the Spanish civil war, a stint driving ambulances in London during the Blitz and administrative war work at Australia House, she returned home. Her later life was beset by breakdowns and periods of institutionalisation, although she still managed to publish original poetry and translations of poems from French, German, Spanish and Russian.

When I was researching my biography of Aileen Palmer, I was disappointed to find there was no trace of this thesis in her papers at the National Library. Surely, I thought, she would have kept something as important as that for posterity. Even if the university kept the copy she submitted, we know that her father bound two — the original and the carbon copy. Its disappearance remained a mystery until recently, when I was contacted by a historian who researches the history of psychoanalysis in Australia to say she had come upon a copy of Aileen’s thesis. Here was another instance of the unfinished business of biography, which had become clear to me when Aileen’s lost portrait was revealed after my book was published.

For several years, Christine Vickers has been researching the life and work of Clara Lazar Geroe, a Hungarian psychoanalyst who, with her husband and young son, came to Australia in 1940 as a refugee, sponsored by a group of Australian medical professionals. Clara Geroe’s archive was preserved for forty years by her son George, who chose the State Library of Victoria as the place to which he would donate it. Dr Vickers was in negotiation with the library to hand over the boxes of papers when George died in 2019, yielding more boxes. These later papers included one of the two copies of Aileen Palmer’s honours thesis.

The handover of boxes was delayed while library renovations were completed, and Christine Vickers had access to them for several more months. Having reviewed my biography Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer in 2016 (in which I declared there was no trace of the thesis), she contacted me to let me know it had been found. It was a valuable discovery. But why should Aileen Palmer’s honours thesis have ended up in the papers of a Freudian psychoanalyst?

Nettie and Vance Palmer’s influence on their brilliant daughter’s life extended far beyond her formative years. When she volunteered to join the Republican cause in the Spanish civil war, she was determined to free herself from the pervasive shadow of her famous parents. That, however, was not to be. In 1948, living at the family home in Melbourne, Aileen suffered her first breakdown, three years after returning from the war zones of Europe. Her parents swung into action, contacting the medical professionals among their circle of friends.

Nettie had become interested in psychoanalysis in 1940 when she met and befriended Clara Geroe while teaching English to refugees from war-torn Europe. Aileen was hospitalised at a private hospital founded by Reg Ellery (one of the psychiatrists who had sponsored Clara Geroe’s move to Australia), where she was subjected to a barrage of insulin coma therapy, electroconvulsive shock treatment and drugs. Before she left hospital after six weeks of treatment, Aileen began a long period of psychoanalysis with Dr Geroe.

Aileen’s illness became very much a family affair. Her sister Helen had a job typing up private notes for Geroe, and Vance wrote to Nettie when she was away lecturing that Geroe had told Helen that Aileen was “making a good fight of it.” Issues of patient confidentiality do not appear to have been paramount. Although she was initially willing to cooperate, Aileen’s experience was not successful in the long run. She became severely depressed after more than a year of analysis and returned to hospital.

At my request, Christine Vickers scanned the opening and concluding chapters of Aileen’s thesis.* There on the page, handwritten over the faded typescript, were the French accents described in Nettie’s diary. The crossings out and handwritten corrections scattered through the text would never be acceptable today, but they are a reminder of how technology has changed the standard of presentation we take for granted.

The handwritten title on the worn cover page of the flimsily tacked-together pages indicates why Aileen may have given the thesis to her psychoanalyst: “Marcel Proust et La ‘Dissociation de la Personne Humaine’” (“Marcel Proust and ‘The Dissociation of the Human Personality’”). The fact that she put the quotation mark incorrectly between “La” and “Dissociation” indicates her rush to make the deadline. I imagine her grabbing her pen and dashing off the title on the front of the copies before she headed for the bus to the university.

In essence, Aileen’s thesis is a rebuttal of the position of the highly conservative French Catholic literary critic Henri Massis on contemporary literature. As outlined in his book Defence of the West, published in 1928, Massis argues that a “depression of energy” and a “resignation of critical spirit” were linked to the dissociation of the human personality. As Aileen writes, Massis believes that “‘Identity has collapsed’… such that, if one wishes to re-establish literature, it would be necessary, he says, to ‘rediscover man, the reality of the spiritual being that a dissociative psychology has destroyed.’”

Taking a historical perspective on what Massis sees as the dissolution of the stability of the moi (self/mind/identity), Aileen argues that what she refers to as dissociation was not new — that it was the sixteenth-century essayist Montaigne who established “the cult of the interior life that nourishes our modern psychologists.” By the nineteenth century, poetry, she asserts, had made such a descent into “the maelstrom of the moi” that for the symbolist poet the external world was “nothing but a projection of his own dreams.” She asks how it is possible for the more expansive genre of the novel, which needs “to represent the variety of life,” to exist when “the most sensitive and sincere writers are mostly resolved to flee from external reality.”

The answer, she suggests, lies in the seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time (published between 1913 and 1927), in which Proust makes no attempt to reunite the contradictory beings of which he is composed except in one work of art. (At the end of the last volume, Time Regained, the narrator realises that memory can only be recaptured and Time defeated through art. He leaves the party he is attending to write a great novel and thus bring the past back to life.) Aileen argues that “this division between himself, which we find elsewhere among the majority of his characters, is at the basis of this ‘dissociative psychology’ of which this series has furnished the greatest example in modern literature.”

Having pursued her analysis of the work in the next four chapters, Aileen asserts in the concluding chapter, “I have tried to demonstrate that this dissociative psychology is not some sort of aberration; on the contrary, it is the height of the development which made itself felt more and more during the nineteenth century.” Proust, she says, does not look back to a particular era in the past: “It is the idea of the past which is not separate from us that stands out in his work.” She contends that “the method of dissociative psychology is necessarily the deepest and truest… Literary art of this genre is not the representation of a simplified reality but the reconstruction of the movements of the human mind with all their complexity.”

The thesis finishes on an optimistic note with a Marxian twist, proposing that “this society that crumbles before our eyes” is not “some mystical decline of the West”; rather, that we could “find in this disarray the seeds of a new society.” That society would sweep away competition and the exploitation of the working classes; no one would have to work too hard; and machines would leave people free to think of things of the spirit.

With the influence of thinkers like Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, the biographical integrity and certainty of characters in the nineteenth century novel gave way to the fluidity and instability of characters in the modernist novel. This knowledge is commonplace today. But Aileen Palmer was writing her thesis on Proust in 1934, only seven years after the last of the volumes of In Search of Lost Time was published. Even my brief and incomplete summary indicates why her examiners (as Nettie recorded in her diary) pronounced it “astonishingly original.”

At twenty, Aileen set off for Europe having achieved a first-class honours degree. She had a letter accepting her request to join the Communist Party of Great Britain in her bag and a desire to fight fascism in her heart. Marx House in London was her first port of call. A reading of parts of this newly found thesis highlights the tragedy of this brilliant young woman’s later life and gives it added poignancy. I wonder how her psychoanalyst responded to it. The State Library of Victoria now has the thirty boxes of Clara Lazar Geroe’s papers in its possession, so perhaps more will be revealed when I can look through them once they have been catalogued. •

* My thanks to James Renwick for his translation from the French.