The Magician

By Colm Tóibín | Pan Macmillan Australia | $32.99 | 498 pages

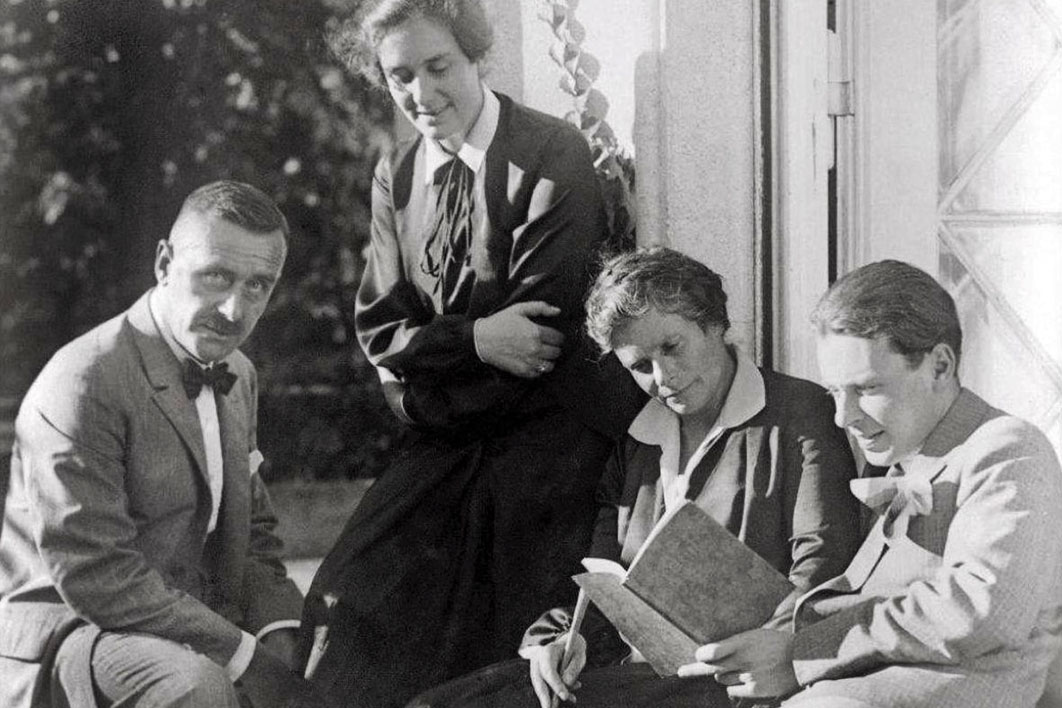

Apart from the pleasures of its prose, Colm Tóibín’s The Magician brings to life a great German novelist whose writing loses much of its irony and lightness in translation. Tóibín’s novel gives us a compelling and intimate portrait of a writer, his family and his times, capturing Thomas Mann for the English-speaking world.

The novel starts quietly, with three chapters on Thomas’s early years, his early, hesitant homosexual feelings and his first novel Buddenbrooks, which traces the decline of a nineteenth-century mercantile dynasty in the northern German city of Lübeck. Then, in chapter four, it bursts into life.

Here we enter the twentieth century, the lively, bustling city of Munich and the lavish world of the Pringsheim family, whose daughter Katia’s wealth, wit, style and social standing attract Thomas. In a series of salon scenes and loaded dialogues Tóibín shows the couple coming together and recognising their need for each other. Katia is the only woman who will ever attract Thomas, and he offers her release from her family into adulthood and the opportunity to disentangle from her relationship with her twin brother, the incestuous elements of which are thematised in Thomas’s short story The Blood of the Walsungs. (Look no further for evidence of a clunky translation than this interpretation of the one-word original, Wälsungenblut.)

Thomas and Katia’s wedding night is told in a sensuous paragraph; by the chapter’s end, four of the couple’s six children have been born and we are off and running.

Tóibín’s commanding knowledge of Mann and his work would be sufficient for a straight biography, but the novel form provides him with two advantages. The first is the opportunity to imagine scenes for which no biographical evidence exists, such as the couple’s wedding night, and to work with images, episodes and dialogue to convey social and domestic scenes and moods. Tóibín also adds colour with cameo figures drawn from the Manns’ circle of family and friends, injected at just the right time to move the narrative on.

In chapter four, the cameo is Katia’s father, Alfred Pringsheim, who rails at Thomas for violating the family’s privacy in The Blood of the Walsungs (which extended to references to Alfred’s own extramarital affairs) and causes the work to be pulled from print for twenty years. Then, as if to assert an overarching control, he insists on furnishing every room of the couple’s new flat, including Thomas’s refuge, his study.

The second advantage of the novel form is that it allows Tóibín to compose scenes by combining factual accounts with Mann’s fictional work. This is true to Mann’s own approach; he openly acknowledged that he not only appropriated material from other authors’ works but also drew on people he knew, including himself. As Katia’s mother, Hedwig Pringsheim, once acutely observed, “Thomas Mann, his family and surrounds — living material for the work of the novelist.”

Chapter four concludes with an account of Thomas’s sister’s suicide and his mother’s decline towards dementia and death. These are part of the real-life drama of 1910, but Mann also used them thirty-seven years later in the climax of his late masterpiece Doctor Faustus. There, amid death and decay, the composer Adrian Leverkühn suffers a collapse into unconsciousness, brought on by syphilis.

Thus, over 500 pages that are neither overlong nor dense, Tóibín’s account faithfully follows Mann’s life to its end. The Magician rattles along with the family through the upheavals of the twentieth century.

The rise of the Nazis caused the Mann family to leave Germany, first for neighbouring countries, and then to America, where their older children, surviving several misadventures, joined them one by one. Thomas was highly influential in both America and Germany as an opponent of the Hitler regime, and the three oldest children, Erika, Klaus and Golo, worked in the English-language press and the American army and intelligence service.

After the war the family’s patriotism was called into question by American anti-communist ideologues. Their existence was made so uncomfortable that in 1952 Thomas and Katia moved back to Switzerland, where they had first found refuge outside Germany nineteen years earlier. Thomas died there, aged eighty, in 1955. Katia lived to be almost ninety-seven, and in her nineties recounted her Unwritten Memories to her youngest son, Michael, and the writer Elisabeth Plessen.

Tóibín manages a large cast of characters, using the cameos to great effect. The six children, in particular, pop in and of the account, and Tóibín touchingly relates one of Thomas’s finest hours as a parent when he banishes Klaus’s terror of ghosts through magic tricks and is dubbed “the Magician” by Erika. It is a nickname that the whole family, not least Thomas himself, finds fitting.

Others who make entertaining appearances include W.H. Auden, whom Erika marries to obtain an English passport and whose smirking presence unsettles Thomas; Alma Mahler, who swirls across several scenes invoking her famous deceased husbands; and the composer Arnold Schoenberg, whose ideas about music Thomas borrowed so liberally for his composer Adrian Leverkühn that Schoenberg felt compelled to publicly deny that he, like Leverkühn, suffered from syphilis.

Thomas and Katia’s marriage is the crimson thread through the narrative, their love holding firm for fifty years of marriage. Their children were not all so steady, though, and Erika’s and Klaus’s adventures with sex, drugs, song and dance spanned Europe and America. Erika’s affairs included an old family friend of her father’s age, the conductor Bruno Walter, whom she dubbed, in opposition to her father, “the Demon.” But Erika also remained the most closely attached to her parents. She followed them to Switzerland after the war and together with Katia fiercely guarded her father’s posthumous fame.

Tóibín uses a straightforward narrative style. Although this is a novel about a novelist he eschews any postmodernist self-consciousness or double-coding techniques. The closest he comes is the intermingling of biographical and fictional elements.

Occasionally Tóibín’s intermingling is overly obvious. In chapter five, for example, Tóibín draws attention to the fact that Thomas’s visit to Katia in a Davos sanatorium was pivotal to the writing of The Magic Mountain. Removed from her normal routine Katia had lost her sense of time, and Thomas too feels the unreal atmosphere. But Tóibín labours the point when he has Thomas feeling that he had been drawn there by “magic” and had fallen victim to “sorcery,” while the “bewitched” Katia has to be roused from her slumber and woken to reality. This almost descends into bathos when Thomas seeks “to break the spell” by talking about building a new house in Munich.

Fortunately Tóibín rescues this episode with a beautiful scene in which Katia returns home while Thomas is still turning the sanatorium experiences into a book:

He did not know whether to tell the children immediately or let her homecoming be a surprise for them. As he waited, he understood that it would not be long before Katia would fill their lives as though she had never been away. He, on the other hand, would, in his imagination, inhabit the life of the very place she was leaving.

Occasionally, too, Tóibín overdoes cultural references. For example, he has Thomas ruminating on Oscar Wilde’s fate when he fears the exposure of his own erotic fantasies. This helps makes the point for English readers — and the reference has been singled out for praise by the New York Times’s critic — but Wilde would barely have been on Mann’s cultural radar. And while there is a connection between the composer Gustav Mahler and the protagonist in Mann’s Death in Venice, Gustav Aschenbach, Tóibín overstates the point when he makes the composer the inspiration for the novella. This strikes a chord with the celebrated film of Death in Venice, made sixty years later, in which Mahler’s music plays a starring role, but the inspiration for the novella was Mann’s private drama and the real model for Aschenbach was none other than Mann himself.

I mention these minor blemishes because they show Tóibín’s determination to make Mann accessible to his readership, using references that have resonance for us. This helps to highlight Tóibín’s singular achievement in The Magician, which is to make Thomas Mann more accessible to an English-language readership than ever before. The great critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki called him “the most German of all the German writers of our century,” and that characteristic has been an impediment to an appreciation of Mann and his work in English. Mann’s works are all available in translation but are no longer widely read and risk being regarded as artefacts from the German past.

Mann cut a formal, even crusty figure in America, and the sheer length of some of his works added to the view that they were longwinded and tedious. The New Yorker played on this view when, following the English publication of his thousand-page Joseph epic, it quipped that “Thomas Mann threatens to become one of the greatest living bores.” Mann’s work has not benefited from fresh interpretations or influential editions in English, except for the superbly filmed Death in Venice, which has recently attracted a revived interest because it takes place in a pandemic.

By contrast, his reputation has remained vibrant in Germany. Since the 1970s the publication of his and his family’s diaries and letters have excited public interest by revealing the seemingly endless series of affairs, scandals and tragedies experienced by the children and the family’s associates. New versions and reworkings of Mann’s work continue to be published, and most recently his rip-roaring picaresque novel Confessions of the Confidence Trickster Felix Krull has been filmed for a third time with a screenplay by Germany’s new literary superstar, Daniel Kehlmann.

Colm Tóibín has bridged this cultural gap and given the English-speaking world a great portrait of Mann and his family, bringing them alive with a fast-moving narrative, dramatic scenes, snappy dialogue and a dash of poetic licence. •