Truth-telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement

By Henry Reynolds | NewSouth Publishing | $34.99 | 288 pages

Return to Uluru

By Mark McKenna | Black Inc. | $34.99 | 272 pages

The signatories of the Uluru Statement from the Heart seek a “fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia” and a process of “truth-telling about our history.” Historians are well placed to answer that call and the publishers have made sure, in their choices of endorsers, that each of these books is presented to the buyer as a response to Indigenous solicitation. What truths have these two distinguished historians elected to tell?

Henry Reynolds’s Truth-telling argues that neither in its legal doctrines nor in its official public memory has Australia come to terms with the historical scholarship that narrates Australian history as violent invasion and land theft on a massive scale. Colonial sovereignty is Reynolds’s main topic in the first half of the book. Reviewing the words and actions of James Cook in 1770 and instructions given to Arthur Phillip in 1786, he depicts “an astonishing assertion of sovereignty that had almost no credibility in international law.” From 1788, “the gap between law and reality, law and colonial experience, grew progressively wider” as the colonists encountered what many admitted was an ordered Indigenous society. Reynolds piles up quote after quote demonstrating that Aboriginal society “captured the attention of curious settlers” — not least when Aboriginal people objected violently to the newcomers’ treating the land as their own.

Reynolds points to nineteenth-century moments in which the British government admitted that Indigenous Australians were proprietors — an accommodation to reality made by imperial policy in other parts of the British Empire. In Australia, however, the British failed to turn that recognition into policies that preserved any Indigenous property rights, and this failure recurred as the colonists assumed “responsible government” in the 1850s and then federated as an independent nation in 1901. “Land rights” didn’t gain political traction until the last third of the twentieth century, and in 1992 the common law (articulated by the High Court) recognised that all of Australia had once been Indigenous property and that some portions remained under “native title.”

As Reynolds has pointed out before, to acknowledge “property” is one thing, to admit Indigenous “sovereignty” is another. Australian law has never worked out what to say about Indigenous sovereignty: for the High Court, sovereignty is a question beyond “municipal” jurisdiction. Australian law has merely affirmed and reaffirmed that Indigenous Australians are subjects of the imposed sovereign. Their “protected” status should at least have shielded Indigenous Australians from harm, but as Reynolds abundantly illustrates, the colonial sovereign was often negligent, often mistaken in its practices of protection, and often fearfully homicidal.

Because Reynolds doesn’t review what colonial policies have been effectively ameliorative, he risks not connecting with readers who believe that — notwithstanding Australia’s terrible past — good policy and law have become possible, without any change in “sovereignty.” He wants Australia to consider “some form of surviving, subsidiary, Indigenous sovereignty.”

Had he explored what could be practised as “sovereignty” in the early twenty-first century he might have evaluated the Indigenous Land Use Agreements signed under the Native Title Act, for some believe them to be regional “treaties.” Would Reynolds agree? His book focuses on harms and failures, and that is salutary; but he does not tell us what “protections” have been beneficial to Indigenous Australians. Few historians acknowledge that the twentieth-century recovery of the Indigenous population is a benefit of protective colonial authority, constituting the very peoples that now assert sovereignty. Perhaps “protection” (in the wider sense of ameliorative law and policy) has some achievements worth defending? Are Closing the Gap and the Indigenous Voice to Parliament causes worth fighting for?

Indigenous sovereignty is present in this book more as a defeated moral principle than as a feasible legal and political project. When Reynolds commends the Uluru Statement, it is for asserting Indigenous Australians’ “ancient sovereignty,” but how is that “ancient” thing now to “shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood’? Answering that question would commit us to evaluating what we are now doing right in contemporary law and public policy, but Truth-telling is almost entirely concerned with the damage we’ve done.

“Truth-telling” is a civic mission to which any historian can sign up; it’s what we are paid to do. Because the truth of Australia’s past is infinite, selecting exemplary stories will be necessary, and so “truth-telling” enjoined by the Uluru Statement may start to form a “canon.” (“Canon” is Megan Davis’s word — no doubt carefully chosen — when she commends the story that Mark McKenna’s book tells.) What would Reynolds put in that canon? Which truths does he want Australians to learn to live with?

Reynolds makes two big points. He reminds us that colonial conquest affected Indigenous Australians region by region — that is to say “nation” by “nation.” At Federation, much of the territory deemed “Australia” still wasn’t under effective colonial occupation; much of the continent was under undiminished Aboriginal sovereignty and much was shared between pastoralists and Aboriginal people figuring out how to live with thinly scattered newcomers. He admits to being uncertain about the legal implications of this fact. The question “When was colonial sovereignty?” has no obvious answer. For those considering such governance problems as how to structure “the Voice,” Reynolds’s reminder that colonial occupation was a two-century sequence of steps has enormous implications, as it is one of the enduring sources of Indigenous Australia’s regional differentiation.

As well, Reynolds argues that the failure to recognise Indigenous sovereignties made violence inevitable as colonial occupation extended. Reminding us how violent that process was, he gives estimates from recent research by others — particularly about Queensland and its Native Mounted Police. What will be the effect on “the national story” of revealing that perhaps 40,000 Aboriginal people were slain by other Aboriginal people licensed and paid by the Crown? Reynolds wants to add the violent conquest of Australia to Australia’s military heritage as “our most important war.” I would add: “and the most morally complex war we have ever tried to commemorate.”

Indeed, the magnitude of Indigenous complicity makes new narrative demands for which the authors and supporters of the Uluru Statement may not yet be prepared. Neither Anzac orthodoxy nor revisionist history has so far imagined “patriotism” so tragically. “Truth-telling allows us to weave new stories and to make old ones richer while, at the same time, more complex,” Reynolds wisely advises.

Stories work by having characters, but how to characterise the Native Mounted Police? How would truth-tellers choose from the “over eight hundred troopers’ names” that historian Jonathan Richards has found in the records of the Native Mounted Police? And would we ever have enough biographical information to guess at the circumstances and motives of those chosen?

It is more likely that we will continue to point the weapon of truth at the august figures whom we credit with the triumph of the colonists. Reynolds gives Sir John Forrest, Sir John Downer and Sir Samuel Griffith as examples of men honoured for their nation-building whose memorials we must now reconsider. “What should Griffith University do?” he asks. The question is well targeted — not only because Griffith was attorney-general or premier in three administrations between 1874 and 1893, presiding over much frontier murder, but also because in 2019 a dispute about the teaching of Australian history (not mentioned by Reynolds) demonstrated to the leaders of that university how difficult it can be to reconcile academic autonomy with clamorous Indigenous opinion about what is “true.”

Mark McKenna’s approach to weaving new stories and making them complex focuses on individuals of exemplary colonial violence: a white man, Constable Bill McKinnon, and three Aboriginal trackers, Carbine, Barney and Paddy. In October 1934, southwest of Alice Springs, McKinnon shot and killed an Aboriginal man, Yokununna, who had escaped from custody with five accomplices, all suspected of murdering another Aboriginal man, Kai-Umen. At the inquest into Kai-Umen’s death, the trackers reported McKinnon’s brutal treatment of his prisoners, and at the trial of these prisoners, their counsel further questioned McKinnon. His answers worried the Commonwealth government and soon there was an inquiry.

The reasons McKinnon gave for killing Yokununna were self-defence and to prevent further escape. The inquiry concluded that the shooting of Yokununna “though legally justified, was not warranted.” McKinnon had told the inquiry that when he had fired his gun (into a cave where Yokununna was hiding) he had not taken aim and was not expecting to hit him. McKenna’s research has uncovered a note in McKinnon’s logbook in which he revealed his intention in firing.

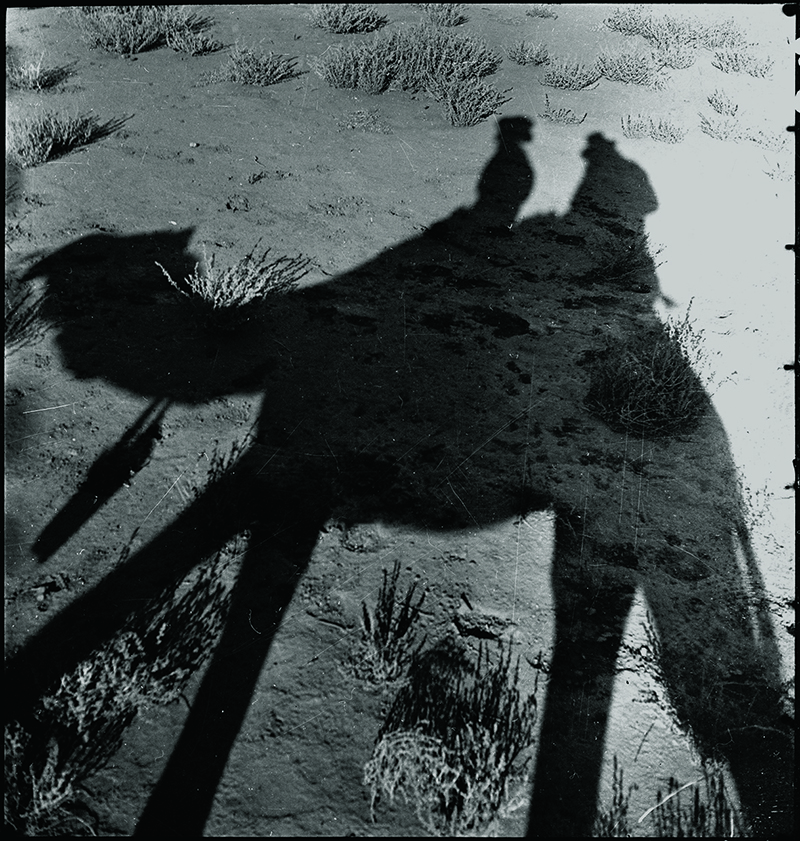

Silhouette of a camel being ridden near Uluru by T.G.H. Strehlow and Charles Mountford during the inquiry into Bill McKinnon’s shooting of Yokununna. Charles Mountford/State Library of South Australia

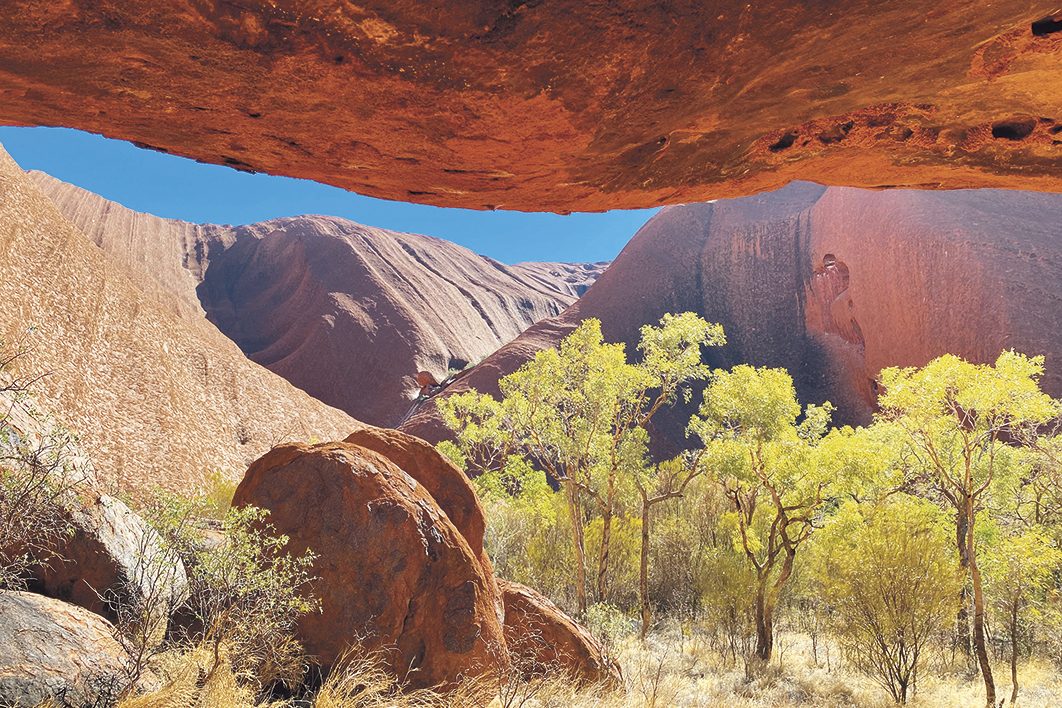

A gifted storyteller, McKenna enriches this sequence of events with fascinating details of person and place, for what makes the story particularly interesting to him is that the cave in which McKinnon shot Yokununna is at Uluru. As a historian, McKenna has become interested in the symbolic significance of place — in this book, not only Uluru but even McKinnon’s daughter’s Brisbane garage, where he discovered McKinnon’s revealing logbook. The place to which he continues to return the reader is Uluru, as he explores the idea that what happens at Uluru continues to define Australians to themselves.

The Rock struck awe and a desire for mastery in the first Europeans to see it, and it has since become a destination for tourists who are similarly affected (albeit in greater comfort). The recent debate about whether it is respectful to climb Uluru has compelled us to ask whose perspective must decide that question. The country over which Uluru towers has been the object of a partly successful land claim in 1979 and, since 1985, the site of an experiment in “two-way” park co-management that now affords the visitor some of Uluru’s sacred stories. Uluru has been not only a lying policeman’s killing ground in 1934 but also a place of First Nations assembly in 2017, and we are now debating the “Uluru Statement.” Then there is the question of Yokununna’s remains: will they be returned from a museum to Uluru?

McKenna’s research and storytelling interweave these layers of meaning and lines of time in ways suggesting that this furrowed arkose monolith is our collective, troubled “heart” — the place where “immutable and inextinguishable” Indigenous “sovereignty” is made “visible… as it is at few other places on the continent.”

He adds to this epiphany the following warning (or is it an appeal?) to readers: “Australians have yet to grasp the fact that the core rationale for an Australian republic is not only the severance of our relationship with the Crown, but also the recognition of the Indigenous sovereignty that existed long before the Crown’s representatives arrived.” His misuse of “fact” (for surely this is only an opinion) is a reminder of what can happen when “truth-telling” becomes an eager act of political service. McKenna’s verbal stumble is a mere “blemish” (a handy John Howard word) on the face of his poetry of national sin and redemption, but we can see it as a caution to those taking up the Uluru Statement’s invitation to tell the truth. •