Any week now, parliament will debate whether to pass the Morrison government’s $158 billion tax cuts. A lot has been said since the election about the politics of the cuts, with Labor under intense pressure from sections of the media to pass the necessary legislation, but less about what they reveal of the government’s broader economic plans.

The cuts rest on two assumptions: that Australia’s population will grow more rapidly over the next decade than in any other equivalent period in our history; and that the likely retirement of five million–plus baby boomers will have little or no impact on economic growth, tax revenue or government expenditure.

On that basis, Treasury assumes that the economy will throw off its sluggishness and start growing faster over the next two financial years, then stabilise at around 3 per cent a year. Government receipts will rise, it says, from 25.0 per cent of GDP to 25.5 per cent by 2028, and government payments will fall from just below 25.0 per cent of GDP to around 23.5 per cent.

The government will then be in the happy position of being able to cancel its net debt, deliver steadily growing budget surpluses — 2 per cent of GDP from the mid-2020s — and still make those big tax cuts.

Or will it? Are we really about to enter economic and budgetary nirvana, or are there hidden traps in the government’s plan?

Crucially, this virtuous sequence of events hinges on the rate at which Australia’s population grows over the next decade. And on that question Treasury, and the government, have been less than forthcoming.

In this year’s budget papers, Treasury claimed that Australia’s fertility rate will rise to 1.9 babies per woman from 2021 onwards. But when the Australian Bureau of Statistics last calculated the fertility rate, in 2017, it had fallen to 1.74, the lowest level on record. A return to 1.9 by 2021 would be astonishing. On the basis of this heroic assumption, Treasury expects Australia’s natural increase over the next decade to be 300,000 higher than would be delivered by the recent rate of gain.

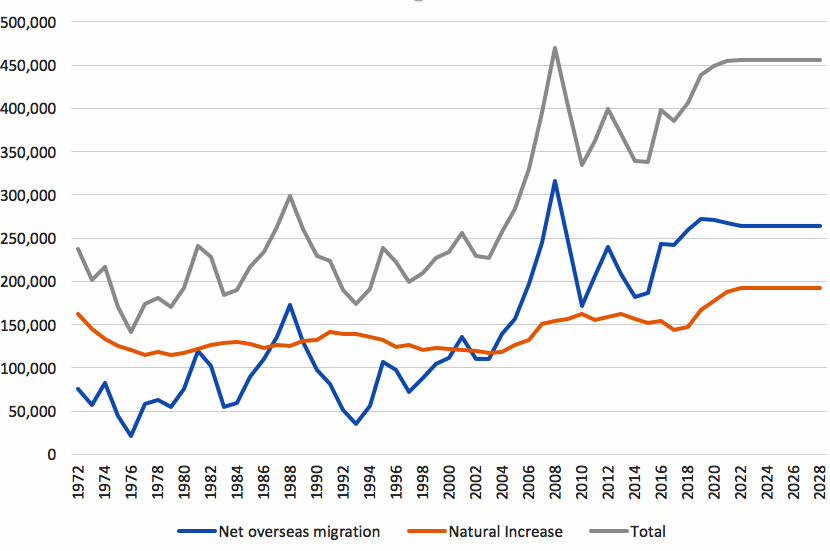

Chart 1. Population growth: migration and natural increase

Source: ABS 3101 and Budget Paper No. 3

Treasury also predicts rapid growth in net migration: 155,000 more people over the next four years than its 2018 forecast, and 400,000 more over the next ten years. But how can that be reconciled with the prime minister’s March 2019 population plan, which included a 120,000 reduction in permanent migration over the next four years that was necessary, he said, to reduce congestion in the biggest cities?

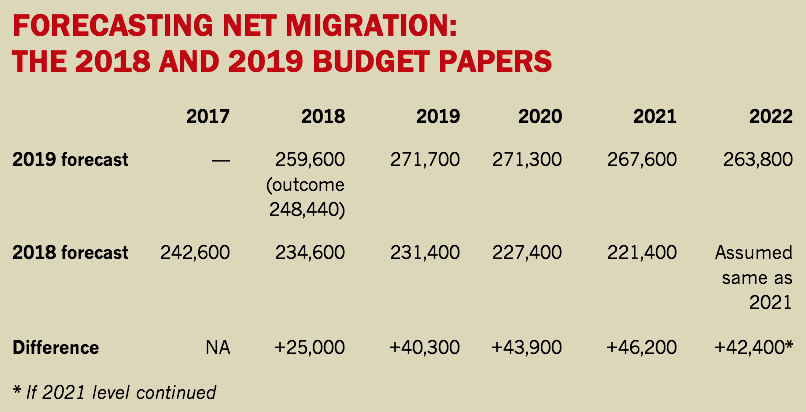

Source: Commonwealth Budget Paper No. 3, Appendix A, 2018 and 2019

If he sticks to that plan, then Treasury’s rise in net migration inevitably means a huge surge in long-term temporary migration to more than offset the reduction in permanent migration. Not a word was said about this during the election campaign, perhaps because it wouldn’t have helped the government’s congestion-busting argument.

So what is going on?

Treasury hasn’t explained how its population growth assumptions square with the government’s economic, budget and tax plans. Higher levels of net migration and fertility would certainly reduce the rate at which the population is ageing. They would also increase pressure on infrastructure and government services.

But on the question of what would happen to the government’s plans if these assumptions weren’t realised, Treasury is silent. As the organisation well knows, a shortfall in the natural rate of increase is likely, and a shortfall in the net migration increase is even more likely, especially as the 2018 figure has already fallen 11,000 short of Treasury’s forecast.

But it is Treasury’s newfound indifference to the impact of ageing that is most surprising.

Launching the first Intergenerational Report back in 2002, treasurer Peter Costello warned of the impact of an ageing population on the economy and the budget. Lower labour-force participation rates and a declining working-age-to-population ratio would dramatically reduce future revenue. At the same time (though some experts dispute this), big increases in health, welfare and aged care spending would be required. Treasury believed that “the gap between spending and revenue could grow to 5 per cent of GDP by 2042.”

Against this background, the Howard government significantly boosted net migration, partly to reduce the rate at which the population was ageing. This decision has helped Australia achieve higher participation rates — all those young migrants looking for jobs — and age more gradually than otherwise would have been the case. And more gradually than comparable countries.

The government also provided a range of major tax advantages to older Australians with access to capital income, designed partly to reduce the growth in the number of people receiving the age pension. In the event, the cost of these measures in lost revenue may well be more than the savings on the age pension.

The ageing theme featured again in the latest Intergenerational Report, delivered in 2015 by treasurer Joe Hockey. “The proportion of the population participating in the workforce is expected to decline as a result of population ageing,” said Treasury, and that means “lower economic growth over the projection period.”

Hockey assumed that “average annual labour productivity growth over the next forty years will be 1.5 per cent” and real GDP growth would average 2.8 per cent a year. Combined with controversial actions to limit spending in health services and the age pension — actions that parliament mostly rejected — he anticipated that productivity growth would quickly put the budget into surplus and net government debt would be repaid by the mid 2030s. It was an extraordinary turnaround from Costello’s forecast of the impact of ageing.

Not to be outdone, Scott Morrison seems to have decided that Costello was far too cautious about the future and Hockey was a wimp when it came to achieving surpluses and repaying net debt. A key element of the PM’s ten-year budget plan is its assumption that the economy will soon return to the level of real GDP growth that prevailed over the two decades between 1998–99 and 2017–18.

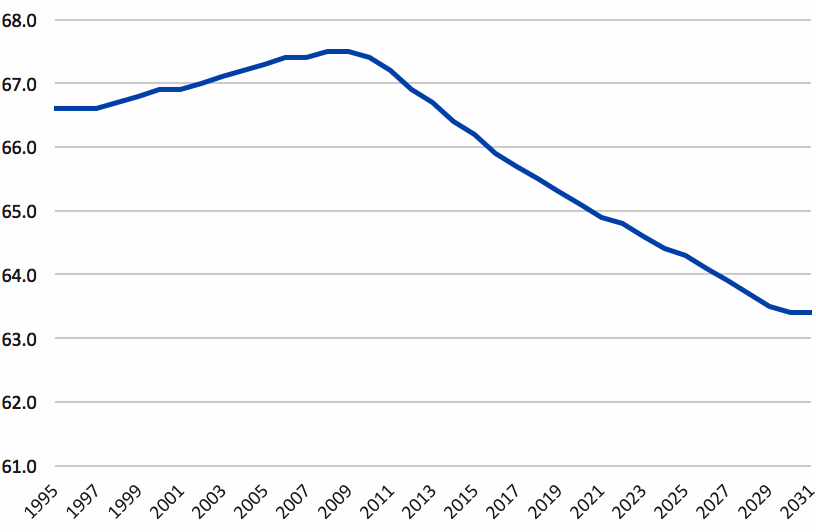

The problem with this view is that during the first half of that period — the decade to 2008–09 — the number of working-age people as a proportion of total population was rising towards its peak of 67.5 per cent in 2009. Most of the 5.5 million baby boomers were at their income-earning peak and were spending at a high rate. Real GDP growth — at around 3.4 per cent a year — was well above the average of the past twenty years.

With the working-age-to-population ratio peaking in 2009 and falling to 65.3 per cent in 2019, real GDP growth has been much lower, at about 2.5 per cent a year.

Using the average of these two periods as the basis for forecasting Australia’s long-term real GDP growth takes no account of the ageing that has occurred since 2009 and its role in slowing economic growth. More importantly, it assumes further ageing will have no impact over the next decade.

Chart 2. Proportion of the population of working age

Source: Parliamentary Budget Office

By 2030, Australia’s working-age-to-population ratio will have fallen to 63.4 per cent. The whole boomer cohort will have moved beyond sixty-five and mostly into retirement. As Costello and Hockey forecast, the downward pressure on participation rates will be considerable.

From 2025, all boomers will be eligible for the pension phase of superannuation and most will be paying no tax on superannuation earnings. Some will be getting large franking credit refunds. Their private household consumption expenditure will fall as they age, and their take-up of health and aged care services and the age pension will increase.

By 2030 the number of Australians aged eighty and over will rise to just under 1.6 million, from around 960,000 in 2016, putting further pressure on the health system. The Australian Medical Association already says the public hospital system is in crisis, and waiting times to enter aged care facilities are under severe strain.

Yet Treasury fails to acknowledge any significant impact of ageing on the economy, tax receipts or the health, welfare and aged-care budgets. Indeed, it now thinks government expenditure as a portion of GDP will fall significantly at the same time as we are ageing.

The independent Parliamentary Budget Office doesn’t agree. In a report released the day before the budget it said:

Since 2011 — when the first of the baby boomer generation turned sixty-five — the share of the population of retirement age has increased significantly and the share of the population of prime working age has begun to fall. This flows through to the budget in the form of a reduction in revenue, due to lower labour force participation, and an increase in spending, reflecting greater demand for government programs that support older Australians. Over the next decade, the ageing population is projected to subtract 0.4 percentage points from the annual real growth in revenue and add 0.3 percentage points to the annual real growth in spending. In real dollar terms, this equates to an annual cost to the budget of around $36 billion by 2028–29. This is larger than the projected cost of Medicare in that same year.

The government knows the likely negative future impact of ageing on the economy and the budget. When the inevitable debt-and-deficit disaster occurs, will it argue for massive cuts in spending like those Joe Hockey attempted? Does it plan to reduce the role of government according to the American model, opening up more privatisation opportunities for the government’s favoured businesses?

And why is it assuming such an extraordinary increase in population growth — and especially growth in the stock of long-term temporary residents — only to hide the fact in an appendix to Budget Paper No. 3 rather than including it in its much-vaunted population plan?

The next Intergenerational Report, likely to appear with next year’s budget, provides the prime minister with an opportunity to reappraise the challenges that an ageing population will pose. It seems unlikely he will take up the opportunity.

Regardless of the pros and cons of immigration or budget surpluses, Australians are entitled to honesty in politics, in the public service and in the media. The government’s assumptions need to be made clear, so the country can make informed and realistic decisions about its future rather than falling for a fairy tale about the good times rolling on forever. •