I once asked my late mother what it was like to get old. “Well,” she said, “it feels like breakfast comes every fifteen minutes.”

Can a purgatory of this kind be avoided? Can you slow down the perception that time is raging like a careening mobility scooter as you approach extinction?

The most famous strategy — as set out in Graham Greene’s novel Travels With My Aunt — is to travel. Greene’s book features a character called Honest Jo Pulling, a wealthy bookmaker who, as the eponymous Aunt explains, “felt that by travelling he would make time move with less rapidity.”

After a long and relatively stationary life, he purchases a ticket on the Orient Express. Unfortunately he’s carried off the train in Venice after suffering a stroke. Undeterred, the adventurous would-be rover buys a ruined palazzo with fifty-two rooms. He moves in and re-embarks on his journey — but this time with a scaled-down itinerary.

Every seven days, he packs his belongings into a weather-beaten suitcase and sets out not for Turkey or Persia or beyond, but for the next room along the corridor. “I’ve seldom seen a happier man,” explains the Aunt. “He was certain that death would not catch him before he reached the fifty-second room.”

Sadly, the old bookmaker dies in transit — between rooms fifty-one and fifty-two. His last words: “It seemed like a whole lifetime.”

The fictional Jo Pulling and the non-fiction writer John McPhee have never met, of course. But they do share a singular idea: it’s possible, they believe, to decelerate senescence.

McPhee has spent much of his professional life turning observation and research into prose for money. Now, at the age of ninety-two, he clearly qualifies as a grandee in the great game of journalism. He’s been a (very) long-time staff writer at the New Yorker; he’s won a Pulitzer; he’s been the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton; he’s written more than thirty books. He is a master — indeed, part inventor — of what the kids call creative non-fiction.

The optimism inherent in his latest book, Tabula Rasa: Volume 1, is fully intended because McPhee claims to have found the secret to eternal life (or at least the perception of it): like Jo Pulling, who never stopped moving, McPhee intends to never stop writing.

“Old people projects,” McPhee explains, “keep people old. You’re no longer old when you’re dead.”

McPhee’s old person project is to resurrect and publish the many stories he failed to deliver for various reasons throughout his long career. Even if he can’t get out on the road — or river, or ocean — anymore, he can still pry open the filing cabinets in his basement and rediscover the faded notes of long-ago false starts.

In this endeavour he claims to have been inspired by his fellow American, Mark Twain. McPhee counts Twain’s autobiography as the greatest old person project in history. Twain wrote it in parts, with the intention of adding chapters of memoir to his existing works, thereby extending their copyright and making money in the future for his daughters.

For this task, Twain counselled a random, digressive, structureless structure, McPhee winkingly explains, with yarns tumbling together like a haberdashery in an earthquake. The great man’s memoir runs to 735,000 words. “If Twain had stayed with it, he would be alive today,” says McPhee.

As any journalist will tell you, finding the story is the hardest part of the job. The second-hardest is convincing an editor to commission it.

Editors in my experience are parsimonious, opinionated to a fault, and casual in their cruelty. When he was Australia’s immigration minister, Philip Ruddock was known in Jakarta as “the minister with no ears.” He was probably an editor in a previous life.

Editors refuse to understand, even when you explain it to them in plain English (something they claim to relish, by the way) that they are making a terrible mistake by rejecting your unquestionably great idea for a story.

Luckily for McPhee, he’s had a few wins. You don’t get Pulitzers for stories you didn’t write.

One day at New York’s Pennsylvania Station back in the early 1960s McPhee stood in front of a new-fangled invention: a machine that automatically juiced citrus fruits for frazzled New York commuters. McPhee saw the flicker of an idea. He finagled an audience with William Shawn, legendary editor of the New Yorker, and delivered his one-word pitch: “Oranges.”

Part of the Shawn legend is the speediness of his response to mendicant writers. Straight away he’d say either “No. Sorry. Not for us” or — as he did in this case — “Yes. Oh, my, yes.”

The pitch turned into a piece called “Oranges,” and then into a hardback called Oranges. And then into several paperback editions, also titled Oranges. It’s possible Mr McPhee’s epitaph will read: “Here lies the guy who wrote a whole book about oranges.”

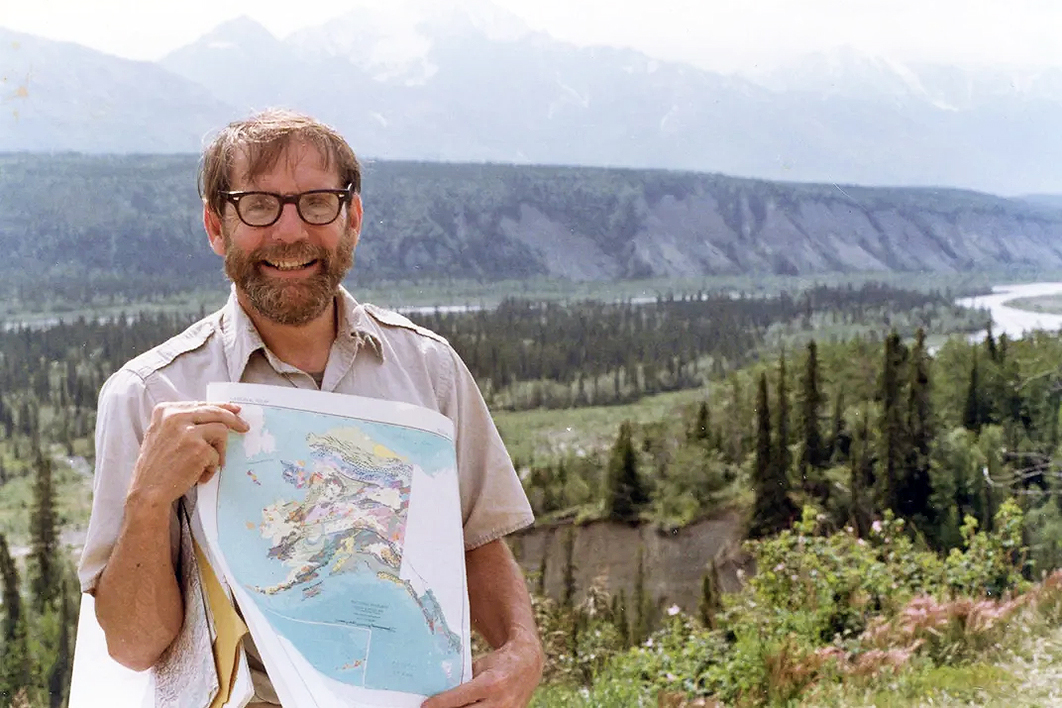

Convincing Mr Shawn to say “Yes, oh, yes” became a passport to adventure for McPhee. He wrote about tennis, nuclear engineering and basketball; about how to make bark canoes and how to explore the Alaskan wilderness. He wrote about rivers and dams. (He loves a good paddle with interesting people.) Much of his best work is about nature, including the slowest story known to humankind: geology.

Like all good journalists, McPhee enjoys the challenge of making the average reader come to appreciate something they may not know they could be interested in.

But, as Tabula Rasa reveals and revels in, sometimes McPhee would schlepp all the way from Princeton into New York on the train only to hear Mr Shawn invoke his paid-up membership of the Editors and Bastards Club by murmuring, softly but definitively, “No. Not for us.”

McPhee wanted to — but never got to — write about golf course architects, the Outward Bound inventor Kurt Hahn, the Swiss bridge engineer Christian Menn, and the Spanish comunidad autónoma Extremadura.

Sometimes it wasn’t Shawn’s fault; sometimes the myrmidons of Corporate America stood in his way. He never, for example, got to traverse California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta on a Unocal tanker called the Cornucopia because the trip was nixed by a party pooper from head office.

Sometimes he did the preparatory work but couldn’t find the right structure. Long ago he wanted to write a piece about The Music Man’s creator Meredith Willson, famed for being the only composer to write not only a Broadway musical’s tunes but also the words and the book. Try as he might, McPhee could never get the idea to take voice and sing.

I could go on. Like many toilers in the Literature of Fact (the name of his course at Princeton), McPhee spent a lot of his precious time on Earth not writing things. Bonjour tristesse.

The flotsam and jetsam of McPhee’s writing career — the features forced down the gangplank, the pieces tossed impulsively overboard, the pet projects abandoned on desert islands — are all brought back to a glowing afterlife in this compact and thoroughly enjoyable book about the endless vagaries (and occasional joys) of the writing life.

According to press reports, the nonagenarian McPhee is contracted to deliver Volumes II, III and IV. He might yet live forever. Let’s hope so. •

Tabula Rasa: Volume 1

By John McPhee | Farrar Straus Giroux | $49.99 | 192 pages