Julia Moore (1925–86), diplomat

Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Julia Moore learnt young about the limits of “leaning in.” Six decades before Sheryl Sandberg sold the illusion that chutzpah could smash glass ceilings, Moore discovered through painful experience that talent, hard work and ambition were no match for a system designed to keep women down. Her encounter with this grim reality began in 1943, when she was among the first women allowed into Australia’s diplomatic service. By 1946, aged only twenty-one, she was a voice of Australia at the United Nations. Just months later, though, her diplomatic career stuttered and died when, as a newlywed, she fell victim to the public service’s long-running “marriage bar.”

Moore began life with considerable advantages. She was born into the Drake-Brockman clan, one of Western Australia’s most prominent families, in the midst of the “men, money and markets” boom of the 1920s. Her father Geoffrey was a decorated former Anzac and eminent engineer, and her mother Henrietta an esteemed novelist and playwright. Alongside her younger brother Paris, Moore was raised in Perth, where her father worked in the Public Works Department. Feminism was an early influence thanks to her maternal grandmother, Roberta Jull, a leading women’s rights campaigner and one of Australia’s first female doctors.

After matriculating from St Hilda’s Church of England Girls’ School, Julia began an arts degree at the University of Western Australia. But life changed dramatically in 1941, when her father was called up for war service and the family moved with him to Melbourne. At their new home in South Yarra, the family entertained Miles Franklin, Ernestine Hill, Nettie and Vance Palmer, Paul Hasluck and other literary and political luminaries. Julia, who had transferred to the University of Melbourne, soon left formal study to work as an assistant librarian at the ABC.

Meanwhile, the wartime labour shortage had induced the Department of External Affairs to make an unprecedented concession: in response to urgings from feminist Jessie Street, it agreed to recruit women into the diplomatic service. When the Diplomatic Cadet Scheme was established in 1943, three of the initial twelve places were reserved for women. In total, 1500 people applied — among them many of the nation’s best and brightest women, who had scant other opportunities for a professional career.

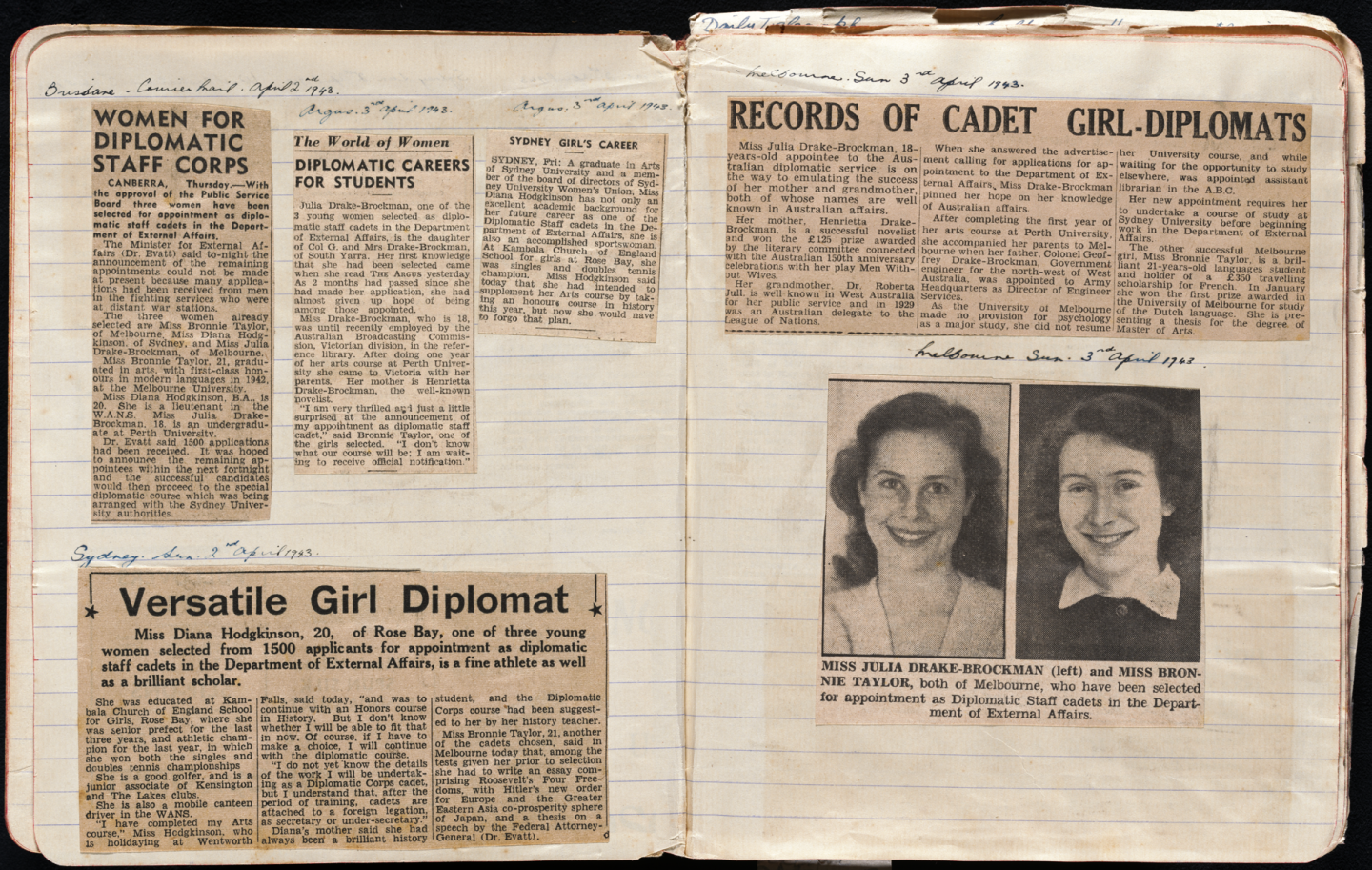

In April 1943 came the much-anticipated announcement: Australia’s first female diplomats were to be Sydney University graduate Diana Hodgkinson, Melbourne MA student Bronnie Taylor and — youngest of all — eighteen-year-old Julia Drake-Brockman. Overnight, the trio became minor celebrities. The Australian Women’s Weekly profiled them; Miles Franklin telegrammed her congratulations; young admirers sent fan mail.

Julia and her fellow cadets were sent first to Sydney, where they completed an intensive training program at the university. Then, in January 1944, the cohort joined the Department of External Affairs in Canberra. What followed, though, was a period of boredom and frustration: the wartime bush capital had few excitements, and Moore was assigned dull clerical work. Although she’d been promised an immediate overseas posting, her male superiors now prevaricated — a delay she attributed to sexism. Within six months, Moore was “fed up,” she told her parents, and threatening to resign.

After two long years, Moore was appointed third secretary to the Australian delegation to the United Nations. She travelled to New York in April 1946 and settled into a new office on the forty-fifth floor of the Empire State Building. At this point, she should have been exultant. Not only was she finally overseas, but she had also won a plum post in a storied metropolis that was the antithesis of white-bread Canberra. Yet a complication was lurking in the wings.

Back in February, she had become engaged to John Moore, a fellow Australian diplomat also bound for New York. Although deeply in love, the couple feared what their nuptials would mean for Julia’s career. As was standard at the time, her appointment was subject to the Public Service Act, which stipulated that “every female officer shall be deemed to have retired from the Commonwealth Service upon her marriage” unless an exception was granted by the Public Service Board.

In an attempt to dodge the issue, Julia and John concealed their engagement. Only in mid 1946, with both of them safely in New York, did they make the relationship public. After a quiet wedding attended by colleagues, they briefly honeymooned in New Jersey and then settled into a small apartment on West 187th Street. Determined to combine love and career, Julia threw herself into what she described as a “strenuous” schedule of office work, committee meetings, official social engagements and weekend overtime — all alongside unassisted housekeeping.

She began “waging a war” with authorities back in Canberra. As predicted, once she had become Mrs Moore the Public Service Board insisted she resign and be re-engaged as local staff, without diplomatic rank and on a lower salary. With the support of her husband, she petitioned external affairs minister H.V. Evatt and head of mission Paul Hasluck to take up her cause. In making her case, she insisted that she had joined the department on “the specific understanding that there would be no discrimination against the women cadets.” While Evatt, at least, was privately sympathetic, neither man proved willing to defend her position.

As this conflict dragged on, Moore began to make headlines for her work on women’s issues at the United Nations. In November 1946, she represented Australia on the UN Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Committee, where her impressive speech helped secure the resolution that all member nations should grant women equal rights. Later she worked alongside Jessie Street on the Commission on the Status of Women. The irony here was rich: just as Moore became the international face of Australian support for gender equality, her own career was on the brink of oblivion because of institutionalised sex discrimination.

In the end, the Public Service Board allowed Moore to retain her position as long as she remained in New York. But she and her husband were able to endure the gruelling workload for barely a year. Back in Australia in late 1947, Moore accepted that her career was “sunk,” and exchanged UN meetings for family life in Sydney’s North Shore.

By this point, Diana Hodgkinson and Bronnie Taylor had also married and been forced to resign. Within less than five years, all three of Australia’s first female diplomats found themselves pushed back into the home. And nor were other women encouraged to step into their shoes. Across the entire 1950s only three female cadets were admitted to the diplomatic service, and it was not until 1974 that Ruth Dobson became Australia’s first female ambassador. The marriage bar, meanwhile, lingered until 1966.

In Sydney, Julia raised four children and was employed as a social worker. John joined the NSW Bar in 1947, and in 1973 was appointed president of the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. He was knighted in 1976 and appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia a decade later. Julia — now Lady Moore — died that year, and John followed in 1988. Later, the Julia Moore Prize in Industrial Relations was established in her honour at the University of New South Wales.

The family tradition of professional excellence continued into the next generation. The couple’s son Timothy served as a NSW Liberal MP (1976–92) and later a jurist, and his brother Michael became a judge of the Federal Court. Yet their mother’s career is almost forgotten, confined to a brief line or two in little-read histories. Only a cache of letters at the National Library preserves her fierce ambition and equally fiery struggle against the marriage bar. •