Growing Up Communist and Jewish in Bondi

By John Docker | Kerr Publishing | three volumes, from $34.99

Lined up in front of me are three hefty volumes: one blue, one yellow, one green. Together they have taken me on a journey through the life of a mind. Not any old mind — although that too could be fascinating, which is why psychology is always of interest and why novels are written and read — but the whimsical, challenging, pugnacious, passionate, utterly delightful mind of one of the most risk-taking thinkers this country has produced.

All along the journey I’ve tried to come up with an arresting opening sentence that would do the experience justice, the hook to entice other readers to take the journey themselves. But my mind has been sparking like a Catherine wheel, and it’s been impossible to settle on one. All I can tell you is that for all my many years of reading and reviewing, Growing Up Communist and Jewish in Bondi has been a highlight for me.

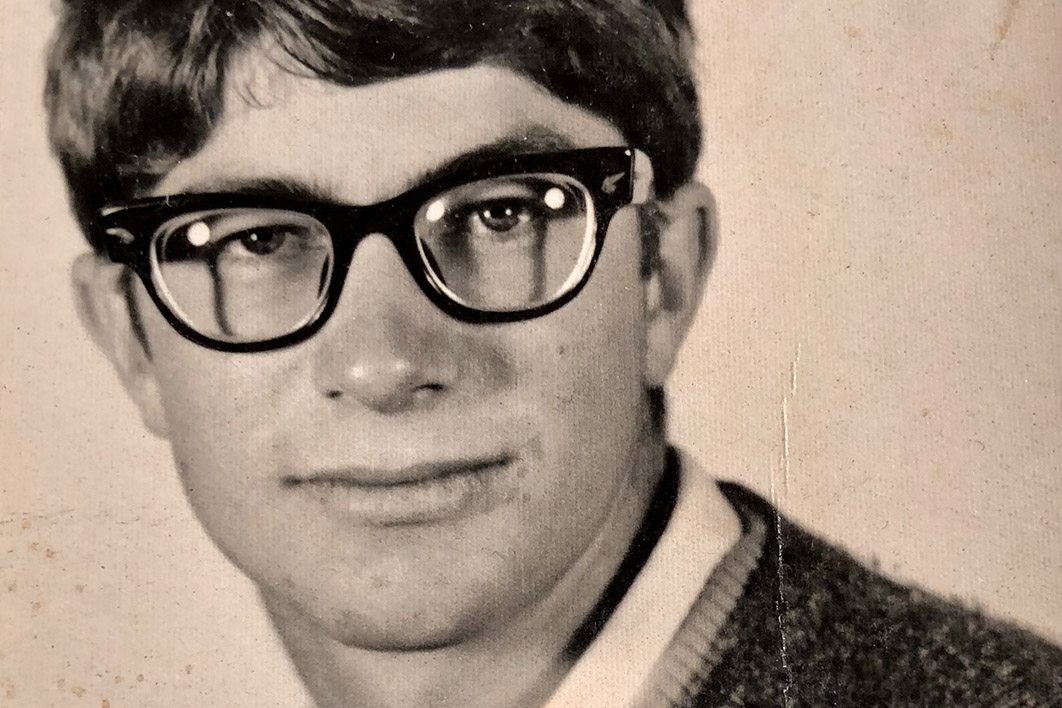

If you think the three volumes comprise a memoir you’d only be partly right. We learn that John Docker, the author of eight books and many essays and articles, was born on 8 October 1945, has had a varied career in academia, is the partner of Ann Curthoys and the father of Ned Curthoys, both of whom are academics. His parents were communists: his father Ted Docker, a carpenter, was a founding member of the Australian branch, established in 1920; his mother, Elsie Levy, having migrated at fourteen with her family in 1926 and started work in factories soon after, was also active in the party. There were seventeen years between them and they produced three children, two girls and then John — a spoiled and irritating child, as he tells it, who at the age of seventy-five somehow considers himself a failure.

Yet what makes Docker’s so different from most life stories, whether memoirs or autobiographies, is that his is less about himself than the people and ideas that have shaped him. In the 1960s and 70s, a deeply formative period for him, we feminists maintained that “the personal is political.” An explosive concept then, it led to the erosion of the line between public and private, heralding the momentous changes society has undergone since. But it’s not been without its problems.

If we invert the word order, we can get an inkling of what’s been lost. Is the political personal? To Simone de Beauvoir, one of Docker’s many influences, the answer was most decidedly yes. It was she who insisted on what she called “political passions,” that ideas about the world and its workings can drive us as much as hormones or intimate family relationships — that ideas can set us alight.

Docker’s framing idea is the ego-histoire, or “ego history” — a category of writing that excited his interest after friends referred him to the works of Pierre Nora, a French historian credited with establishing the method and giving it a name. In essence it’s a freewheeling text in which the narrator’s experiences spark affinities with the lives and thoughts of others. What also distinguishes the three volumes is that these sudden, often surprising connections frequently correspond to pivotal changes in the narrator’s life. There isn’t the space here for further explanation; the important thing here is that with Docker it works.

As well as members of his family, colleagues and friends, the characters wandering in and out of the history include Hannah Arendt, T.S. Eliot, Isaac Deutscher, Georg Simmel, Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, F.R. and Q.D. Leavis, Henry Mayer, Mikhail Bakhtin, Raphael Lemkin, Mohandas Gandhi and the above-mentioned Pierre Nora. All these and more have imprinted themselves on the narrator’s psyche, but the two most powerful influences, to the point where they could be taken for the author’s lodestars, are Baruch Spinoza, the seventeenth-century Jewish philosopher excommunicated by his synagogue for heresy, and Walter Benjamin, the twentieth-century German-Jewish intellectual who, fleeing from the Nazis, met his untimely death in the Pyrenees, on the border between France and Spain.

There’s a nice link here. If it weren’t for the fact that Hannah Arendt, another refugee and close friend of Benjamin’s, had made it to the United States, Docker might never have heard of him. Such are the contingencies of human existence. It was Arendt who, by gathering some of Benjamin’s pieces and having them published in America as Illuminations, introduced him, posthumously, to the English-speaking world.

What then, decades later, has been Benjamin’s significance for Docker and, for our special interest, the particular form these books have taken? There is more than one affinity. Like Docker, Benjamin was never able to acquire a permanent foothold in academia. He too was fascinated by popular mass culture; unlike Adorno, Marcuse and others of his more high-minded colleagues in the Frankfurt School, he didn’t dismiss it, but saw how it drew on earlier demotic traditions that challenged existing feudal orders.

Benjamin’s insights here coincide, in Docker’s perception, with those of the Russian Mikhail Bakhtin, whose ideas of the orchestrated social eruptions of early modernity have become signal features of Docker’s evolving worldview. Throughout his narrative these are repeatedly encapsulated as the favoured carnivalesque or “upside down” social events — demonstrations, street theatre, soap operas. He was also struck by Benjamin’s preference for fragmented texts over smoothly patterned narratives with decided conclusions. What Docker came to value in Benjamin was his relish for conversation and the open-ended nature of his discourse, risking ambiguity but expanding instead of stultifying the intellect.

Overall, Growing Up is a model of this kind of sensibility, signifying in its exposition the very possibility of change. Reading it is both invigorating and enlightening, though I don’t, of course, agree with everything in it. I think Docker is a bit hard on Leonard Woolf, for example, who like Docker himself underwent a significant political conversion. For Woolf this meant giving up his upper-middle-class pretensions and embracing a left position. For Docker it entailed breaking from his father’s influence. The titanic confrontations that took place between father and son in the family’s small Bondi flat exemplified the New Left’s repudiation of the hierarchical, puritanical, doctrinaire Stalinism of old.

In the process, Docker found himself increasingly in sympathy with his mother’s Jewishness, which he explores in the second, largest volume in the trilogy. This is where I’ll turn my attention for the rest of the review.

Back to Hannah Arendt then. After arriving in the United States she used her connections with refugees who had preceded her to resume her literary career, and writing in English as well as her native German. A non-observant Jew, she was nonetheless seared by the rampant anti-Semitism she’d experienced in Germany and was dismayed to encounter in America. A key essay published in 1951 interrogated the manifest failure of European Jews to be accepted by the prevailing national majorities, no matter how “assimilated” they were, and distinguished between two categories of Jewish accommodation: the “parvenu” and the “conscious pariah.” In the first she included Zionists who’d collaborated with the Nazis; the second she filled with men like Spinoza and the poet Heine, to mention just a few.

Docker deploys these distinctions throughout, as a means of measuring what it is of value to him in the Jewish experience. It’s hardly surprising that Arendt’s insights would carry weight with me, Jewish and non-observing myself, but saying this risks detracting from how well they inform Docker’s narrative or the deftness with which he springs from Leonard Woolf and Bloomsbury to T.S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism to Walter Benjamin’s possible suicide in the Pyrenees and to the Jewish Youth Theatre productions his mother and uncles put on in Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

Those familiar with Docker’s 1492: The Poetics of Diaspora, published back in 2001, will recognise some themes. Until these volumes came along I would have readily nominated that book as one of my favourites. In it Docker examined the impact of the fall of Muslim Spain and the catastrophic expulsion in 1492 of its Jews by Catholic Isabella and Ferdinand. Not only was this the cause of much Jewish suffering; it signalled the rise of the nation-state, and the loss of the centuries-long convivencia, in which Muslims, Christians and Jews had lived in relative harmony.

There are those who’d reject Docker’s rosy picture of the convivencia, but the point remains — history shows that partition along ethnic lines, practised by colonial powers ever since, has disrupted and destroyed cultures and left millions dispossessed and dying. Especially in his second volume, this point leads Docker to Raphael Lemkin and the UN genocide convention he lobbied for, which in turn leads to an investigation of the sources of human violence, and then to Gandhi’s concept of ahimsa.

For Jews compelled to don the mantle of Arendt’s “conscious pariah,” nothing disturbs quite so much as the Zionist project for creating a Jewish nation-state. Docker delves into the history and discovers (as I did researching my great-aunt’s story for the novel that would become As the Lonely Fly) that there had once been another kind of Zionism.

What Zionists like Martin Buber and Judah Magnes wanted was a bi-national state, one to accommodate both Jews and Palestinians, who in 1948 at Israel’s inception comprised the majority population of the former British Mandate. But the combination of Theodor Herzl’s political Zionism and the Holocaust served to seal the Palestinians’ fate, subjecting them to a second-class citizenship and a seventy-two-year-old brutal occupation, which to Jews like Docker and me and many others is anything but Jewish.

Inevitably in a project such as this — a three-volume ego history that wends its way through the author’s thought processes — there’s a fair bit of recurrence, yet for all that, Growing Up Communist and Jewish in Bondi is rarely if ever repetitious. The only time I felt myself getting antsy was when he documented the 1970 success of the campaign to dismantle the ridiculous censorship that bedevilled Australia. Docker and Ann Curthoys decided with a filmmaker friend to do something about it, and inaugurated a program of direct action, picketing the theatres showing films that were cut and taking on the distributors. In keeping with Walter Benjamin’s relish for using a variety of texts, Docker includes a series of newspaper articles tracking the course of the action, which included a screening of banned pornography; it did begin to pall.

But the section reveals a lot about another success, arguably as impressive as stopping the censor from butchering films and getting an “R” classification for adult ones. I’m referring to the partnership between Docker and Curthoys, one that has lasted fifty-one years through periods of social transition that have ripped apart many other relationships, a partnership that in the significance of the work it’s produced could be counted in some ways as an Australian version of the one between Sartre and de Beauvoir, and seemingly a happier one. And Docker is the first to acknowledge that it was Curthoys, a half-century ago, who introduced a callow postgraduate student to Simone de Beauvoir and sent him on this unforgettable journey. •