India captivated me more than fifty years ago when I taught English in a government high school in Chandigarh. Since then I’ve rarely had a day when I wasn’t talking, reading or writing about that country. And I need to talk about India and Australia now. There’s a lot going on.

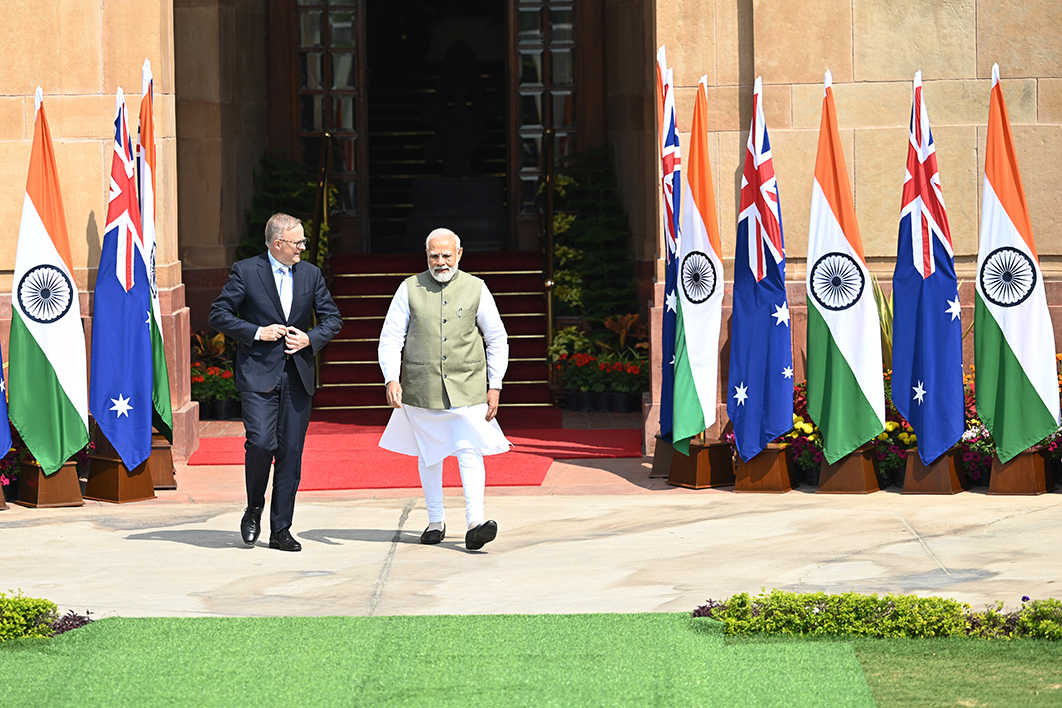

Let me start with the good stuff — the connections. Australia–India relations have had enthusiastic moments in the past, but the visit of prime minister Anthony Albanese this month, coinciding with a cricket tour, made the biggest splash by an Australian PM since Bob Hawke’s bromance with Rajiv Gandhi in the late 1980s.

Albanese’s Australian companions included leaders from education, business and government. The Quad — the strategic engagement between the United States, Australia, Japan and India — was tactfully discussed, and two Australian universities bravely proposed to set up campuses in India. Albanese rocked gracefully in the decorated golf cart that carried him and Modi around Ahmedabad’s vast cricket stadium for the Indian prime minister’s lap of honour on his home turf.

What was underplayed in the commentary was the third pillar of a dynamic relationship: people. The other two pillars — shared economic and strategic interests — are already there in burgeoning trade and the enthusiasm for the Quad.

But the permanent ingredient is people — people going back and forth between India and Australia every day for family, business and professional reasons. When Bob Hawke and Rajiv Gandhi were courting in the 1980s, fewer than 20,000 Australian residents had been born in India; today people of Indian origin number closer to a million. And that’s excluding people from India’s South Asian neighbours, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Afghanistan.

The arrival of Indian-origin Australians in public life will gain enhanced national attention now Labor’s election in New South Wales has resulted in Daniel Mookhey’s becoming treasurer. Mookhey is the nephew of someone I taught in years 6 and 7 in the Boys’ Basic High School in Chandigarh. His uncle and late father came to Australia in the 1970s.

The list of recognised high achievers is growing rapidly. The NSW Australian of the Year in 2022 was Veena Sahajwalla, a professor of materials science. The Victorian Australian of the Year in 2023 is Angraj Khillan, a medical doctor, and the NSW Australian Local Hero is Amar Singh, founder of the charity Turbans 4 Australia. You’ll find similarly talented people throughout business, medicine, law, education and the public service, all of them in addition to the thousands of young people making a start in Australia by doing some of the tough jobs, most visibly in transport.

This growing presence brings assets Australia urgently needs: initiative, talent and youth. But the assets come with challenges. People from other places invariably bring beliefs and ideas that can prove a puzzle to the new country.

Prime minister Modi identified one such challenge when he admonished Albanese for not preventing hostile graffiti on Hindu places of worship in Melbourne and Brisbane.

The graffiti are part of an international attempt, made easier in a world of Twitter and its many cousins, to revive the fifteen-year Khalistan insurgency that subsided bloodily thirty years ago. “Khalistan” was the demand for a sovereign state for Sikhs, who form a majority in the Indian state of Punjab and are a large component of the Indian diaspora in Britain, Canada, the United States and Australia.

The secessionist movement of forty years ago grew out of political upheaval in India and its neighbours in the late 1970s. It was compounded by a sense that Sikhs had long been taken for granted and by a lack of employment in Punjab, where green-revolution agriculture brought a margin of prosperity but a decline in the need for labour. The fact that some of those conditions are still noticeable helps to explain the recent aggressive Khalistan demonstrations in Britain, the United States and Canada.

The notion of Khalistan is likely to puzzle most Australians. Those bloody days in north India and overseas had largely disappeared from international media by the mid 1990s, but many wounds remain. Australia’s current high commissioner to India says he’d not encountered the term “Khalistan” until he arrived in India.

Modi’s Khalistan reprimand highlights the need for broader understanding within all Australian institutions of the pulls and pressures the diaspora may face.

Other issues also require recognition of both political sensitivity and enduring scars. An example is the different suppositions about marriage and family that prevail in India and Australia. The subtitle of Manjula O’Connor’s recent book, Daughters of Durga: Dowries, Gender Violence and Family in Australia, captures some of the strains faced by migrants, and by people who work with them.

A third issue is caste. Caste discrimination is illegal under the Indian constitution, but still widely encountered. Prejudice against Dalits (formerly disparaged as “untouchables”) now shows up sufficiently in Britain and the United States for Seattle’s city council to pass a motion banning it. A bill to ban such discrimination in California has also been introduced in that state’s senate.

Finally, Australian governments and institutions need to decide how they deal with Narendra Modi’s government. There would be much to admire in Modi’s life story and in the political and social apparatus he has helped to build. But the scaffolding rests on the founding principles of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or RSS, the Hindu-supremacist organisation Modi joined as an adolescent and made his career in. The RSS was inspired by the racial-superiority movements of interwar Europe.

The leader of today’s RSS captured aspects of this outlook in an interview in January. “Hindu society has been at war for 1000 years,” he said, and “this fight has been going against foreign aggressions, foreign influences and foreign conspiracies… This war [today] is not against an enemy outside, but against an enemy within… Foreign invaders are no longer there, but foreign influences and foreign conspiracies have continued.”

Modi’s India steers towards a narrow authoritarianism, demanding conformity to an RSS vision of what it is to be a Hindu. International media organisations like the BBC are held up as examples of the “foreignness” that needs expunging. A BBC documentary reflecting poorly on Modi when he was chief minister of Gujarat during fearful riots in 2002 was banned in India earlier this year.

The ban was followed by “surveys” (not “raids,” the government said) of BBC offices in New Delhi and Mumbai looking for financial violations, and outrage at George Soros’s suggestion a few weeks later that “Modi is no democrat.” Soros pointed out that Modi and business figure Gautam Adani, whose vast holdings have suffered since a critical report by a US-based short-selling specialist, have been close over twenty years and Modi “will have to answer questions from foreign investors and in parliament.”

Questions in parliament are looking less likely since the speakers of both houses have effectively closed off discussion. Rahul Gandhi, the most prominent of the opposition MPs, has been expelled from parliament and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment on charges of “criminal defamation.” (If the same grounds for defamation prevailed in Australia, the prison system would need expanding.)

None of these internationally publicised incidents touches on the everyday harassment that many Muslims, Christians and even Dalits experience at the hands of grassroots zealots implicitly encouraged by their leaders.

Most Australians don’t share “values” such as these. In future, Australian speakers at bilateral occasions, when they feel the need to praise India, might choose to endorse the words written in capital letters in the prologue to India’s 1950 constitution: JUSTICE, LIBERTY, EQUALITYand FRATERNITY. Give “democracy” a rhetorical rest. •