This Generation: Dispatches from China's Most Popular Literary Star (and Race Car Driver)

By Han Han | Translated by Allan H. Barr | Simon & Schuster | $30

China in Ten Words

By Yu Hua | Translated by Allan H. Barr | Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd | $25

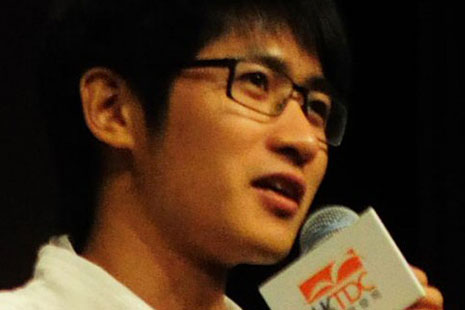

HAN HAN and Yu Hua are very different writers, but they have produced highly complementary books that are among the most important translated works about China published in many years. Han is the sometimes flamboyant symbol of China’s internet generation, the teen rebel who scandalised society and won a massive youth following when he dropped out of his Shanghai high school, wrote a novel about it, and went on to pursue his dream of becoming a race-car driver. While continuing to write novels, he has flirted with pop stardom and has become, over the past decade, China’s (and presumably the world’s) most-read blogger.

Yu Hua is of an earlier generation: born in 1960, he came of age during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), an era that casts a long shadow over the books that made his name, from the grim black humour of To Live, famously filmed by Zhang Yimou, to the grotesque, rollicking epic Brothers. Growing up long before the internet allowed for instant celebrity, Yu spent years working as a dentist in a small town in Zhejiang province, patiently mailing his stories to literary editors in Beijing, before he finally embarked on the path to fame.

Yet these two books have much in common, and not just the fact that they are both translated – idiomatically and readably, if at times a little over-wordily – by Allan H. Barr, the American academic who also edited Han’s collection. In each of these works – a selection of blog posts, and an attempt to summarise modern China through ten widely used Chinese phrases – the authors turn a cynical eye on contemporary society, combining well-informed observations with laconic wit to skewer many of China’s problems and faultlines.

Han Han’s blog posts exist very much in the here and now: his acerbic take on current affairs, his caustic style and his apparent lack of fear of official sanction make it clear why he became so popular with a generation tired of empty rhetoric.

Han chides, mocks, satirises. A corrupt official jailed for taking $100,000 in bribes over thirteen years? If only all officials were so honest, he says, and took such a small amount over such a long period. A proposal to jail men who sleep with prostitutes? Three quarters of Communist Party members and many celebrities would be in prison, he suggests. An official pays to sleep with a fourteen-year-old girl but is released with a small fine? “As our propaganda departments would put it, this reflects their patriotism,” he writes. “They love our country, so they love our country’s blossoms [a common Chinese metaphor for a young girl]…”

Official blunders and hypocrisy are the target of many of his broadsides. He attacks the media for attempting to save officials from embarrassment during the opening of the Shanghai World Expo by covering up attacks on schoolchildren. He mocks restrictions on giving secondhand clothes to earthquake victims, and rails at the pollution that has ruined his old neighbourhood. And when China Central Television’s new building is burnt down by its own New Year fireworks in 2009, Han Han says he is trying to suppress his “darker impulses” but can’t avoid the feeling that an organisation with “no media ethics” has courted its own destruction.

But his can be a subtle voice too, and some of his criticisms are buried so far beneath layers of irony that a casual reader might miss them. This is perhaps sometimes an attempt to outwit China’s internet censors, but it’s also a style that strikes a chord with his young readers, among whom a world-weary ennui is often fashionable. Han’s essay “Report on Preparations for the World Rally Championship in Australia,” is a masterpiece of this genre. On arrival from the “Heavenly Dynasty,” he writes, “my first impression was poor: to my dismay no reception party of primary schoolchildren pounding on waist-drums was there to greet us.” Nor, unlike back home, was he invited to meet local leaders. As for the economy, he adds, it was “extremely backward – the price of a large villa with swimming pool is no more than that of a hundred square metre apartment in Shanghai,” while “the local inhabitants live in wretched conditions: on the way from the airport to the hotel I did not see a single Mercedes, BMW or Audi, and the local government is so poor it cannot afford to erect a single toll plaza on the freeway.” Nor does he see a single policeman at the rally site, which, he suggests, “goes to show how weak the forces of law and order are” in Australia.

Yet if attacks on empty pomp and ceremony, sky-high property prices, excessive consumption and obsessive policing are common in his writing, Han is not afraid to take on his own generation either. Many of the extracts date from 2008, when he waded into the various controversies surrounding the Olympics, amid anger with the international media for its coverage of riots in Tibet in the spring of that year. Urging young people not to become aggressive, Han took a series of daring positions: not only did he argue that Chinese people were too sensitive about criticism from abroad, and dare to suggest that China and the Dalai Lama should be friends, but he also noted sardonically that if young people were calling for boycotts of anything connected with France following disruption of the Olympic Torch Relay in Paris, they should boycott the Olympics too, since the modern games “were the brainchild of a Frenchman – Pierre de Coubertin.”

All of this won Han the attention not only of the censors, but also of online critics opposed to his liberal views. He was accused of plagiarism, bigamy, even lying about his height. In late 2011, he courted further controversy when he published three of the essays that conclude this selection, on “freedom,” “democracy” and “revolution.” Now it was liberals who criticised him for his argument that revolution would not be good for China at the present moment because it would most likely bring forth a demagogue as leader, and that the country was not ready for democracy because people lacked the basic respect for the rule of law that he saw as its vital foundation.

Yet these arguments fit in with his general unwillingness to accept received ideas and easy answers; and they are also a reminder of what makes Han Han unique in China – unlike many intellectuals, he has always had a remarkable knack of talking directly to a mainstream, youth audience, in a realistic language they can understand. He says that he no longer believes in the “extreme idealism” of his youth, but he remains a courageous iconoclast, arguing that “what the people most need is to be served, not controlled, and what officials most need is to be controlled not served,” and pledging that if the authorities do not allow greater freedom of expression he will personally stage protests at future meetings of China’s official cultural associations. “I’ll keep on demanding freedom until you can’t stand it,” he warns them.

Han Han has also railed at another legacy of the Cultural Revolution: the tendency of people on the internet, on either side of the political spectrum, to use what freedom they do have online to denounce each other viciously. “There’s no tradition of debate,” he says. “People think if your position is different then they should try to destroy you.” His hope, he says, is that China will ultimately become a more caring society: noting that “democracy often means compromise,” he stresses that “we need more generosity, a more inclusive approach, peaceful dialogue.”

JUST why this might not be so easy is made abundantly clear in China in Ten Words. Like Han Han, Yu Hua sharply critiques current social problems, but with a longer historical perspective. In an attempt to explain the root causes of these problems, he takes the reader back to his Cultural Revolution childhood. Much of the first half of his book reads, superficially, like a memoir of childhood, but the relaxed, coming-of-age style is subverted by frequent references to episodes of startling brutality, the violence made all the more shocking by the matter-of-fact way in which it is described. From the age of seven, Yu watched in “stunned fascination” as rival groups of Red Guards, each swearing allegiance to Chairman Mao, battered each other with clubs in the streets of his hometown “until they had blood streaming down their faces.” He saw one group of Red Guards throw its rivals off a rooftop; he watched public sentencing rallies; and in several cases he and his friends observed executions on the nearby beach, where he saw prisoners’ faces “shattered beyond recognition” by bullets. He saw his friends’ fathers forced to sweep the streets in dunce’s caps – and recalls how one of these “capitalist roaders” later committed suicide to spare his family the shame.

Equally shocking was the arbitrary nature of many of the accusations. Yu describes a loyal government propagandist suddenly denounced as a traitor by a worker’s leader who couldn’t understand the subtleties of the pro-government play he’d written. In a particularly poignant scene, he recalls how he and his classmates wrote a poster denouncing their school teachers, as was the fashion, but left their favourite teacher off the list of targets – only for the teacher to beg them to include his name, so that he would not stand out too much from the pack. The shattering of social bonds, and indeed trust itself, left a bitter legacy, he suggests: he recalls watching two of his female school teachers laughing together in the playground every day, only for one of them to be arrested as a counter-revolutionary and the other to revel in her comeuppance.

All of this left Yu with nightmares about “being hunted down and killed” until well into his late twenties – and it also explains what he describes as the “bloodshed and mayhem of my work in the 1980s.” Although he eventually forced himself to stop writing about such topics, he argues that the revolutionary violence of that period “has continued to rear its head” in Chinese society through the recent decades of modernisation. It’s reflected, he says, in the hiring of thugs to resolve business disputes, in the sometimes violent clashes between urban management officials and street traders, and indeed in the process of urban redevelopment, with its forced evictions and wholesale demolition of old neighbourhoods.

Yu also implies that the shattering of the bonds between the authorities and the people during that period have resulted in a society in which the very phrase “the people” (one of his ten words) has been “denuded” of its original sense of respect – and in which “the government cons the people.” Many of the people, he acknowledges, have become skilled at responding in kind, via what is translated as “bamboozling.” But he suggests that the fact that these efforts to deceive officials are widely accepted is a worrying indication, both of the weakness of the rule of law and of the fact that people often have no choice but to resort to deception in the face of arbitrary rules and regulations.

Yu Hua also depicts the Cultural Revolution as a time when students received little real education. His own thirst for “real” literature, at a time when shelves were filled with the selected works of Chairman Mao and novels of socialist realism, is movingly related. As a result, he implies, the people who have been running the country since then, many of whom grew up in that era, were insufficiently educated for the task of modernisation.

Yu Hua does hail the spirit of ordinary citizens, noting that China’s “economic miracle of the past thirty years” is really “an agglomeration of countless individual miracles” created at the grassroots level by ordinary people who “dare to think and dare to act”; and he sees today’s tendency to make “copycat” products and to spoof official news reports and TV shows online as a reflection of a creative “anarchist spirit,” one that represents a “challenge of the grassroots to the elite, of the popular to the official, of the weak to the strong.”

Overall, however, Yu says, China is suffering from “lopsided development.” It “has fashioned an astonishing economic miracle, but the price it has paid is even more astounding,” he warns, listing “environmental degradation, moral collapse, the polarisation of rich and poor [and] pervasive corruption,” as well as duplicate construction and poor planning. “So intense is the competition and so unbearable the pressure that for many Chinese, survival is like war itself. The strong prey on the weak, people enrich themselves through brute force and deception, and the meek and humble suffer while the bold and unscrupulous flourish.” With many of the urban elite exhibiting “willful indifference” to “the hundred million who still struggle in almost unimaginable poverty,” he says, China has “lost its equilibrium.”

All this may be an inevitable response to what went before, he suggests – and to China’s accelerated leap “from an era of material shortages into an era of extravagance and waste, from an era when instincts are repressed into an era of impulsive self indulgence.”

It is this emphasis on the links to recent history, in a society which sometimes seems to have no past, which makes China in Ten Words particularly valuable. As with Han Han, Yu’s is an authentic and unremittingly honest voice, offering a highly human insight into what this nation has been through – and a reminder that in today’s China, historical memory and critical social commentary are unlikely to be silenced as easily as they once were. •