In a Grattan Institute report released this week, Money in Retirement: More than Enough, we showed that the conventional wisdom that Australians don’t save enough for retirement is mistaken. In reality, most Australians can already expect a comfortable retirement, and that means the plan to increase compulsory super contributions to 12 per cent should be abandoned. Many in the superannuation industry see this as heresy.

We’d all like to be richer in retirement. The catch is that this usually requires being poorer during working life. Finding the right balance is the art of retirement incomes policy. But most industry research on Australians’ retirement incomes has ignored these trade-offs.

The superannuation guarantee requires people to have less income while working in return for higher retirement incomes. We shouldn’t compel people to save more once they have saved enough for “lifetime consumption smoothing” — enough money to fund a similar standard of living in retirement as they enjoy while working.

But many people — particularly those associated with the financial services industry — advocate a much higher standard of living in retirement than this.

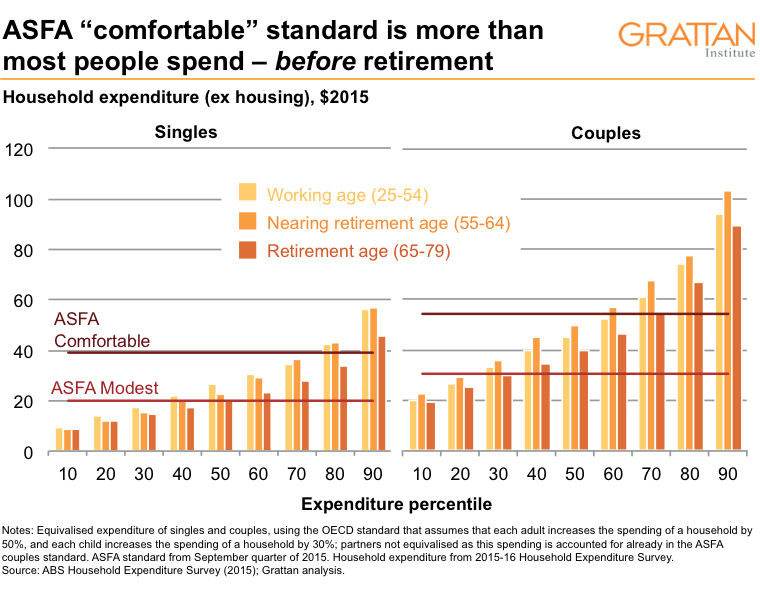

The best-known example is the standards developed by the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia, or ASFA, which have been used in a lot of discussion about retirement incomes. They are attractive because they provide a single number that defines a “comfortable” retirement. But that single number is based on a standard of living that most Australians don’t have before retirement. It isn’t appropriate for most people: they can only be “comfortable” in retirement if they are “uncomfortable” beforehand.

Not only does ASFA think Australians should be much better off in retirement than when they were working, it thinks people will need to spend about 25 per cent more when they’re ninety than they did when they were seventy. ASFA considers a couple aged sixty-five today to be comfortable only if they are on track to be able to spend more than $75,000 a year at age ninety.

Analysis grounded in the reality of people’s actual spending patterns shows that retired Australians tend to spend less as they age and become more frail.

Australians do spend more on healthcare as they age, but Medicare shields them from the full costs. The modestly higher out-of-pocket costs they pay are mainly due to rising premiums for private health insurance. Similarly, government pays — and is likely to continue to pay — for the majority of aged-care costs. Overall, as people age, there are much bigger falls in their spending on travel, recreation and eating out.

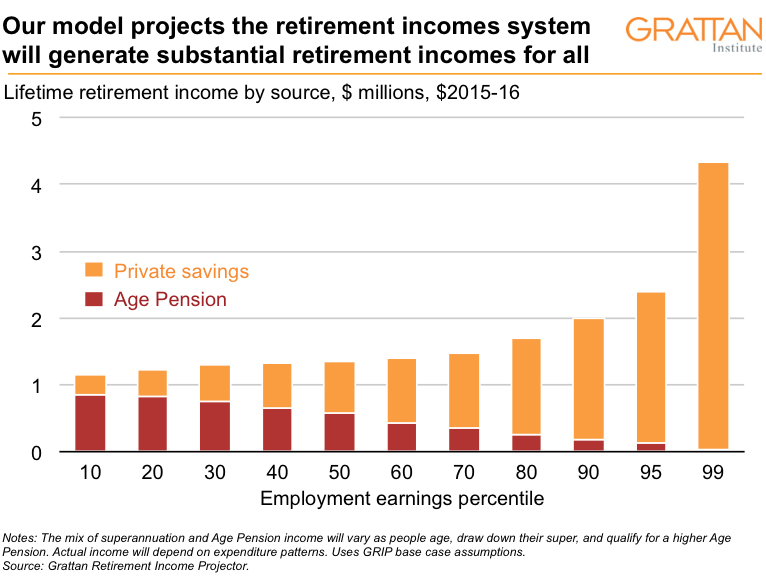

ASFA’s chief executive recently asserted that you don’t have a “dignified” retirement unless you are self-funded. This is an absurdly high standard. The alternative to self-funding isn’t a full age pension. Given means testing, around half the population are likely to qualify for a part age pension on the day they retire, and almost all will qualify for a part age pension if they spend most of their savings through retirement (which is the fundamental assumption of the system). On anyone’s modelling, both savings and the age pension will be important pillars of retirement incomes for many years.

There is no indignity in receiving a part pension: even ASFA assumes that those reaching the “comfortable” standard will be receiving one in retirement.

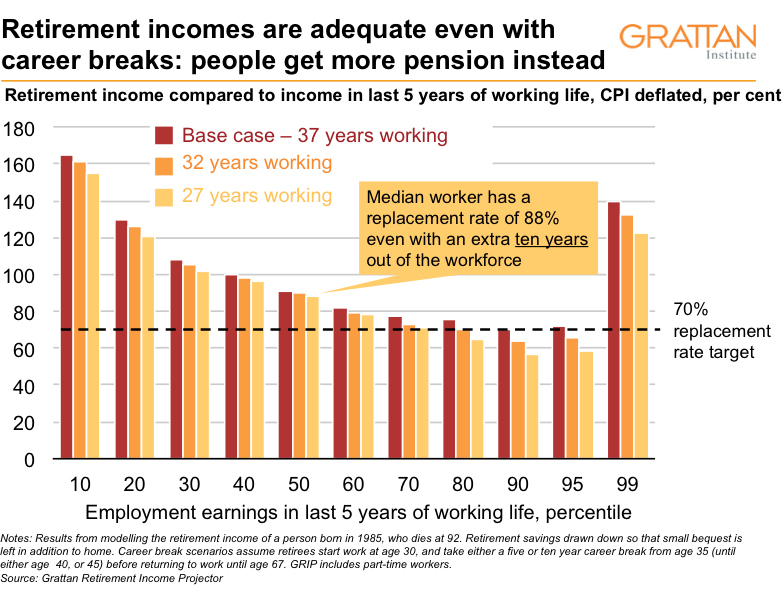

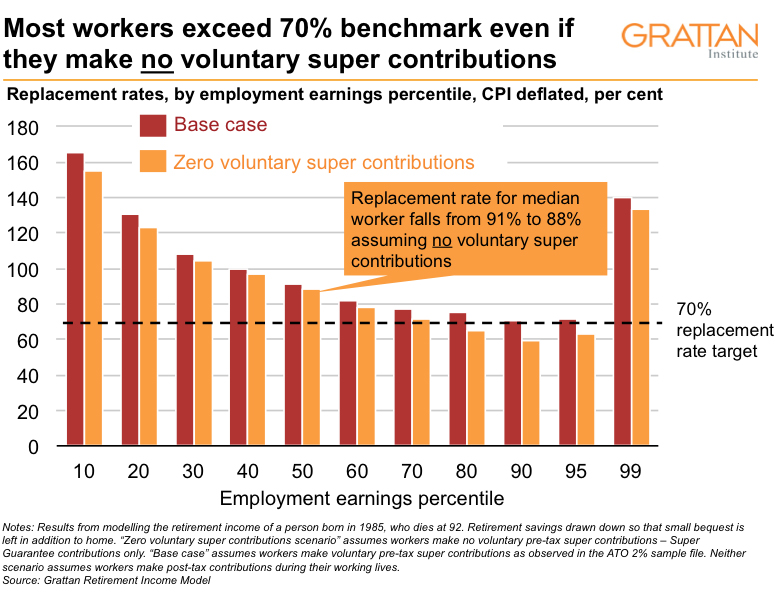

To strike a better balance between money in retirement and money beforehand, we focus on whether workers across all income levels will have retirement incomes at least 70 per cent of their pre-retirement earnings — the so-called replacement benchmark used by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and in the Mercer Global Pension Index. The benchmark is set below 100 per cent because people who own their own home have materially lower expenses in retirement: they’re no longer paying off the mortgage, they’re no longer paying for their children, and they don’t have expenses associated with work.

Our modelling shows that the median (typical) Australian worker can expect a retirement income of 91 per cent of his or her pre-retirement income. And many low-income Australians will effectively get a pay rise in retirement.

Even workers in their forties and fifties today — many of whom didn’t benefit from the present high rate of compulsory super contributions for their entire working lives — can expect a retirement income of at least 70 per cent of their pre-retirement incomes. And many will have much more than this.

ASFA suggests that someone meeting the retirement standard we use, but not meeting the ASFA “comfortable standard,” won’t be able to afford health insurance, a car, an internet connection, or a regular dental check-up. If so, it is very strange that people are able to afford these things during their working life. ASFA’s inability to understand the spending patterns of most Australian households is consistent with its assumption that a retirement standard designed for the top 20 per cent is somehow an appropriate aspiration for everyone else.

Of course, not everyone will be comfortable in retirement: those on low incomes while working will still have low (albeit higher) incomes in retirement. Some — especially renters — are at risk of poverty, but no more so than when they were working. But, as we show, lifting the super guarantee won’t do much to help them

While we can be confident that retirees today typically have enough income to fund a living standard as high as their living standard twenty years ago when they were working, predicting the future is harder. Any attempt to analyse our retirement incomes system requires us to assume things about the future.

A distinctive feature of Grattan Institute’s work is that we spell out our assumptions in detail so that others can see what we’ve done. Most other work in this field is at best sketchy about methodology — and occasionally silent on issues that turn out to be crucial to the results. Our work is also unusual because it calculates and publishes how much the results would change using different assumptions — precisely because people might reasonably differ on these assumptions.

One such assumption — which turns out to matter less than you might guess — is about how people’s incomes change over their lifetime. Contrary to some assertions, our model does not assume that people work full-time, or have uninterrupted careers. Unlike many other models, ours specifically accounts for changes in income as people get promoted, change jobs, or move between full-time and part-time work. Our model mirrors actual shifts captured in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, which tracks individuals over time. In other words, we capture how people (especially women) shift from full-time to part-time work, and back again, over their working lives.

The model doesn’t perfectly capture complete career breaks, where a person leaves the workforce entirely for five years or more. It does assume that a person only starts working and accumulating super at the age of thirty, when in reality most people start work by their early twenties. This builds in some allowance for career breaks. But while career breaks might have a big impact on a super balance, they affect retirement income less. Retirees might have less super to draw down in retirement, but they’ll get a larger part pension. The net change in their retirement income is small for all but the highest-income earners.

For example, if a median-income earner works for thirty-two rather than thirty-seven years, their “replacement rate” will only fall from 91 per cent to 90 per cent. If they work for twenty-seven years, their replacement rate falls to 88 per cent.

Some high earners who take an extended career break may not have incomes in retirement that are more than 70 per cent of the relatively high income they had the day before they retired. This situation — not uncommon for high-income women — embodies the trade-off inherent in retirement incomes. These earners can only maintain their lifestyle from their last few years of working in retirement if they have much less income during their career break, and quite a lot less income for much of their working life.

Whether that is a good trade-off depends a lot on their family circumstances. But legislation should not force high-income women to opt for even higher retirement incomes — particularly if this also effectively forces everyone else to trade off working-age income for retirement income as well.

Another relatively unimportant assumption deals with voluntary super contributions. These are inherently difficult to model accurately. Although only a minority of people in the Australian Taxation Office’s sample of tax returns make voluntary pre-tax super contributions in any year, many more probably make a material contribution at some time over their working life.

Our modelling deals with this by assuming that every year people make the average contribution for a person of their level of income observed in the ATO sample file. In real life, people are more likely to make no voluntary contributions in many years, and then contribute much more than the average in one or two.

Industry Super Australia has made a big deal of this. Modelling assumptions are always debatable. But good modellers only get excited about assumptions if they significantly change the answers. Even if you assume no one makes voluntary super contributions, replacement rates for the median worker would only fall from 91 per cent of their pre-retirement earnings to 88 per cent — still a long way above the 70 per cent benchmark. Excluding all voluntary super contributions has a larger impact on replacement rates for the top end, but this is precisely the group that is much more likely to make larger voluntary super contributions in real life.

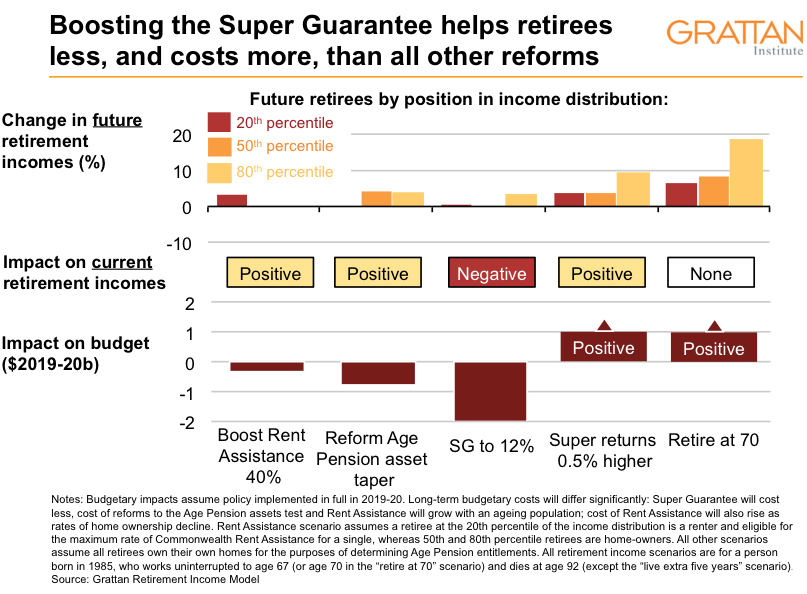

That leaves us with the central dilemma raised by the fact that the legislated plan to increase retirement incomes by lifting the Super Guarantee from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent will reduce workers’ wages today, and make pensioners worse off. And it won’t increase retirement incomes very much, especially for many of those in the bottom 70 per cent of the income distribution. For the median Australian worker, the extra superannuation income will be largely offset by lower part-pension payments.

Higher compulsory super contributions would also reduce pensions in another way. The age pension is indexed to wage growth, which would be lower if employers are required to increase super contributions. So the most fervent opponents of a lift in compulsory super contributions from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent ought to be the pensioners of Australia.

The government ought to oppose it as well. Diverting more of what would have been wages to more lightly taxed super will strain the budget. Scrapping the proposed increase would save $2 billion a year.

Our work shows that the vast majority of retirees today and in future are likely to be financially comfortable. But if we want to raise retirement incomes still further, the current policy of increasing compulsory super contributions to 12 per cent is the worst way to get there. It would cost more, and help low- and middle-income retirees less, than almost anything else governments could do.

The real priority should be to boost Commonwealth rent assistance by 40 per cent, providing an extra $1410 a year for retired singles and $1330 for retired couples. That would cost the federal budget just $300 million a year today. And it would give us by far the biggest bang for the buck in alleviating poverty in retirement.

Senior Australians who rent in the private market are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners. And renting will become more widespread as younger generations on low incomes find themselves less able to afford homes.

Loosening the age pension assets test taper could also boost the retirement incomes of around 20 per cent of retirees today, and more than 70 per cent over time. It would cost the budget just $750 million a year — less than half the cost to the budget of the proposed increase in compulsory super.

And retirement incomes would increase far more — across the board — if default super arrangements were changed along the lines suggested by the Productivity Commission, so that fewer people have their money in funds with persistently low returns.

Nevertheless, the super industry still lobbies hard to raise compulsory super contributions to 12 per cent, or even 15 per cent. It makes you wonder: whose interests are they really looking after? •