For many months, Matteo Salvini, Italy’s interior minister, seemed unstoppable. His Lega party (the successor of the Lega Nord, or Northern League) increased its share of the vote from 4.1 per cent in 2013 to 17.4 per cent in 2018, becoming the third-largest party in the Italian chamber of deputies. Then, in late May 2019, it won 34.3 per cent of the vote in the European parliamentary elections, topping the polls in Italy and performing better than any other far-right party across Europe.

The man whose followers call him Il Capitano (the captain) has been able to position himself as the strongman of Italian politics and the de facto leader of the European far right. He has effectively sidelined both prime minister Guiseppe Conte and Luigi Di Maio, the leader of the Five Star Movement, the nominally senior partner in Italy’s governing coalition.

Salvini is well-known for his racism and for trying to prevent asylum seekers from reaching Italy. His policies and practices have been controversial not least because they appear to contravene Italian and European law, though so far neither Italian nor European courts have issued rulings against him. But it was only a vote in the Italian senate that stopped him from facing criminal charges for directing the coast guard vessel Diciotti not to dock at an Italian port with rescued migrants on board.

Neither Di Maio nor Conte, nor Nicola Zingaretti, the leader of the Partito Democratico, the largest opposition party, have had Salvini’s measure. Even Pope Francis wields less influence among Italy’s Catholics than Salvini, who claims to be a devout Christian and often fondles a rosary in public but has dismissed many of the Pope’s views, particularly concerning the human rights of migrants. According to an analysis published recently by the Guardian, it was former Trump strategist Steve Bannon who in 2016 advised Salvini to go after the Pope.

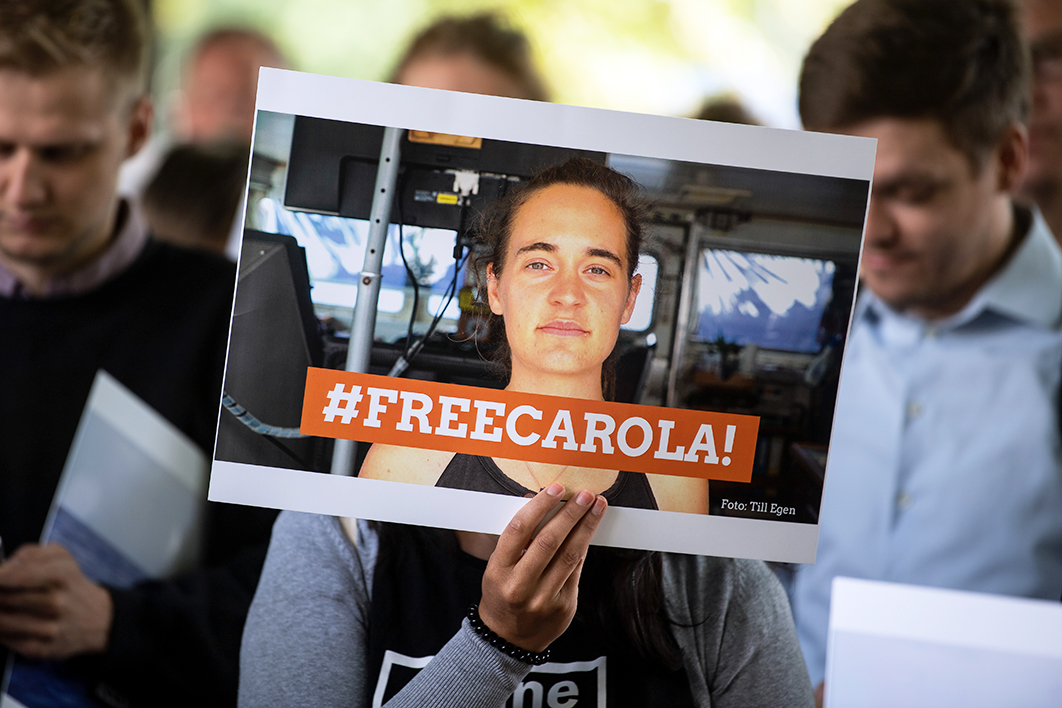

But Salvini might have met his match: thirty-one-year-old Carola Rackete, a German woman who, in Italy, is referred to as La Capitana.

Unlike Salvini, who failed to complete his university studies in history, worked briefly as a journalist, and has otherwise been a full-time politician for most of his adult life, Rackete is a ship’s captain by training. She has a degree in nautical science from Jade University, and worked for several years as an officer on German and British research ships in the Arctic and Antarctic, on cruise ships and on a Greenpeace vessel.

Rackete joined the German activist group Sea-Watch in 2016. The organisation had been established the previous year to keep the European Union accountable by patrolling the Mediterranean and, if necessary, rescuing migrants at sea. Rackete briefly captained the organisation’s Sea-Watch 2 in 2016, and in June 2019 was put in charge of the Sea-Watch 3, a fifty-metre Netherlands-registered vessel built as a supply ship for Brazilian oil platforms.

Over the past two years, Sea-Watch has clashed with Libyan, Maltese and Italian authorities. On two occasions in 2017, dozens of people died because the Libyan coast guard thwarted attempts by the crews of Sea-Watch 2 and Sea-Watch 3 to rescue them. Between June and October 2018, Maltese authorities prevented the Sea-Watch 3 from leaving the port of Valetta because, they claimed, the ship had not been properly registered. In January and May 2019, the Italian authorities tried to prevent the Sea-Watch 3 from disembarking people it had rescued; in both these instances, though, they were eventually landed in Italy to be taken to other EU countries for the processing of their asylum claims.

On 12 June this year, the Sea-Watch 3, under Rackete’s command, rescued fifty-three people in international waters off the Libyan coast. Two days later, the Italian government issued a security decree making it an offence for non-government organisations to disembark rescued migrants in Italy, and provided for hefty fines for noncompliance. Rackete rejected Libya’s offer to let the Sea-Watch 3 disembark its passengers at a Libyan port, because migrants are exposed to torture, rape, forced labour and extortion in that country. She also rejected suggestions by European politicians that she head for a Tunisian port, because, like Italy, Tunisia had closed its ports to migrants rescued in the Mediterranean and has no refugee determination process.

Sea-Watch 3 nevertheless aimed for the Italian island of Lampedusa to disembark its passengers. But while he allowed the medical evacuation of some of them, Salvini prohibited the ship from entering Italian waters. He accused Rackete and her crew of being the “accomplices of traffickers and smugglers” and running a “pirate ship.” For two weeks, the vessel remained in international waters in deference to the Italian government’s order, but on 26 June Rackete declared a “state of necessity” — a provision in international law describing circumstances that preclude the unlawfulness of an otherwise internationally unlawful act — and took the ship to within a couple of miles of Lampedusa.

Three days later, with people on board becoming increasingly restless and the situation threatening to spiral out of control, Rackete decided that she had no choice but to dock at Lampedusa. As the Sea-Watch 3 approached the quay, a much smaller Italian customs vessel tried to block it. A minor collision ensued, with no injuries, and Rackete completed her manoeuvre. Video footage of the incident suggests that Rackete did not deliberately endanger those on board the Italian ship and that it was more likely that the latter’s recklessness led to the accident.

When the German captain left her ship, she was arrested by Italian police and later charged with resistance, violence against a warship, and people smuggling, and put under house arrest. On 2 July, a judge in Agrigento, Sicily, ordered her release after throwing out two of the charges. Another judicial hearing is scheduled for 17 July.

Since her release, Rackete has been holed up at a secret location in Italy. That’s not because she wants to avoid the publicity surrounding her case but because she has reason to fear for her safety. She has been subjected to online abuse and has received death threats. In Germany, former police officer and serial video blogger Tim Kellner published a YouTube video attacking Rackete and her family, which to date has been viewed more than 320,000 times. Most of the more than 3700 comments posted so far applaud Kellner and are informed by hatred. Some contain threats. For example, “Grillgucker” wrote: “A bullet between the eyes would solve the problem.” Others referred to her as Assel (woodlouse) or Zecke (tick), or to her and her supporters as Volksverräter, the term used in Nazi Germany for traitors.

In Italy too Rackete has been threatened with rape and murder, for which Salvini can take part of the blame. He has used social media to attack her, calling her a criminal and claiming that she committed an act of war. Referring to the crew of the Italian customs vessel, Salvini said she had tried to kill five members of the Italian military.

If Salvini’s tone has become more strident, I suspect that’s because twice in the past week he has suffered a defeat. First Rackete was able to defy his order and dock in Lampedusa. Then two of the charges against her were dismissed and she was released from house arrest. Salvini has also attacked Alessandra Vella, the Agrigento judge, claiming her decision was politically motivated, shameful, scandalous and dangerous, and suggesting that Vella resign from her position and seek a career in politics. After her decision, Vella too has been subjected to abuse and death threats. Salvini has also threatened to push for “judicial reform.”

In other, forthcoming court cases Salvini’s own policies and conduct will be closely examined. Last week, Rackete’s Italian lawyer Alessandro Gamberini announced she would launch a libel lawsuit against the minister. At least outwardly, Salvini remained unconcerned about that prospect, writing on Twitter, “She breaks the law and attacks Italian military ships, and then sues me. The mafia doesn’t frighten me, so why should I be afraid of a rich and spoiled German communist.” But now Gamberini has upped the ante: in the fourteen-page statement prepared for the court, he not only claimed that Salvini broke the law on twenty-two occasions, he also asked the court to order the closure of Salvini’s Twitter and Facebook accounts.

But a case before the European Court of Human Rights might provide a bigger headache for Salvini. It concerns one of the incidents in 2017 in which the Libyan coast guard prevented a Sea-Watch ship from rescuing migrants. Seventeen survivors are now suing the Italian government for abetting the Libyan coast guard in their return to Libya, where they were exposed to extreme forms of violence.

If the court finds against Italy, the case might have similar ramifications as the Hirsi case, in which the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2012 that Italy had breached its international legal obligations when returning migrants intercepted in the Mediterranean to Libya under a deal negotiated between the Gaddafi and Berlusconi governments. Italy had been taken to court by a group of Somalis and Eritreans rescued by the Italian navy only to be handed over to the Libyans.

In its ruling, the court found that “the Italian border control operation of ‘push-back’ on the high seas, coupled with the absence of an individual, fair and effective procedure to screen asylum-seekers, constitutes a serious breach of the prohibition of collective expulsion of aliens and consequently of the principle of non-refoulement.” This judgement was behind the decision by the European Union and Italy to use the Libyan coast guard for pull-backs. But it is conceivable that the court will find the pull-backs contravene international law no less than the Italian push-backs of 2009.

There are two more reasons why Salvini has been under the pump. First, the absurdity of Italy’s Libyan solution has again been put into sharp relief. This week, the Italian government announced that it wants to work even more closely with the Libyan coast guard. But Salvini’s argument that the Libyans could rescue and look after migrants trying to reach Europe sounds increasingly hollow. In the early hours of 3 July, a government-run migrant detention centre in the Libyan capital Tripoli was bombed, presumably by the forces of general Khalifa Haftar, who has been waging war against the government in Tripoli. At least forty-four of the detainees died when two missiles struck the centre, and more than 130 were severely injured. According to reports, the centre’s guards shot at detainees who were trying to escape after the first missile hit.

Salvini is also vulnerable as an indirect result of the fact that Italian and European support for militias aligned with the Libyan government has made it more difficult for people smugglers to sell places on small boats leaving from Libya. Why pay money to smugglers when the boat is likely to be intercepted by the Libyan coast guard and its passengers returned to Libya? Smugglers have therefore offered an alternative option: larger ships take people from the North African coast to an area within easy reach of Italy, and there they are transferred to dinghies or other smaller vessels that take them directly to Lampedusa or Sicily.

As a result, seventeen small boats, carrying more than 300 migrants, landed in Lampedusa alone during the two-week stand-off between Sea-Watch 3 and the Italian government. Salvini doesn’t want to talk about them because they make a mockery of his claim that he has been able to seal Italy’s maritime borders to migrants arriving by boat.

Carola Rackete and Sea-Watch have suffered much abuse in recent days, as has the Pope, who used a mass on Monday to speak out on behalf of migrants. But Rackete has also been hailed as a heroine, both in Italy and in her native Germany, and Sea-Watch has received much support, including from unexpected quarters.

Within twenty-four hours of Rackete’s arrest, a campaign launched by two German television presenters had netted more than €1 million in donations, mostly from people in Germany, but a sizeable amount also from Italians. In fact, Sea-Watch has received so much extra funding that the organisation has decided it can afford to share some of it with other organisations running private search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean.

Predictably, politicians from the far-right Alternative for Germany have praised Salvini’s stance and condemned the Sea-Watch captain. Equally predictably, Rackete has been applauded by politicians from the Left and the Greens. Perhaps less predictably, among the first to defend her were the two most popular German politicians, federal president Frank-Walter Steinmeier and foreign minister Heiko Maas. They were followed by the European Union’s budget and human resources minister, and prominent Christian Democrat, Günther Oettinger, and by development minister Gerd Müller of the Bavarian Christian Social Union, the Christian Democrats’ sister party.

Remarkably, Müller has called not only for a resumption of European search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean, but also for an evacuation of refugees from Libya in a joint EU–UN operation. On 8 July he told the Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung that “the people in the [Libyan] camps of misery have the choice of dying in the camps through violence or hunger, to die of thirst in the desert on the way back or to drown in the Mediterranean.” While Angela Merkel hasn’t yet commented on Rackete — or Müller’s proposal, for that matter — a government spokesperson has strongly condemned the criminalisation of private search-and-rescue missions. Even Merkel’s bête noire, hardline interior minister Horst Seehofer, wrote to Salvini to ask for the reopening of Italy’s maritime borders.

Sea-Watch’s and Rackete’s responses to the rhetorical support they have received from the federal government have been lukewarm. They have pointed out that Germany has also provided funding and logistical support to the Libyan government, and that more than words are needed.

The German print and electronic media have largely rallied behind Rackete, and have often been critical of the Italian government and the European Union. Numerous newspapers have published long feature articles about the deaths in the Mediterranean and the tussle between Salvini and Sea-Watch. Last Saturday, Germany’s premier news magazine Spiegel ran a cover story about Rackete. Most of the articles in the German media have avoided portraying the conflict in national terms, even though Salvini has tried to make much of the fact that Rackete is German.

Across Germany on the weekend, tens of thousands took to the streets in around ninety separate protests against Rackete’s arrest, the criminalisation of rescue missions in the Mediterranean and the German government’s complicity in migrant deaths. In Hamburg, about 4000 people marched under the slogan “Free Carola,” although the organisers had expected a crowd of only 1500. In Berlin, 6000 turned out for the same cause.

While European governments took their time to agree on the distribution of the people rescued by the Sea-Watch 3, there has been no shortage of offers to accommodate them. In Italy, archbishop Cesare Nosiglia of Torino said that his archdiocese was willing to take care of the migrants from the Sea-Watch 3. In Germany, several towns and cities have offered to accommodate migrants rescued in the Mediterranean — over and above those asylum seekers assigned to them by the federal and state governments. Thirteen local councils have formed the Bündnis Städte Sicherer Hafen (Alliance of Safe Haven Cities). Among them is Rottenburg, a town of about 40,000 in Baden-Württemberg in Germany’s affluent and conservative southwest.

Christian Democrat Stephan Neher has been Rottenburg’s mayor for more than ten years. “We want to act globally and take advantage of globalisation,” he said soon after the Sea-Watch 3 announced that it had rescued fifty-three people. “Therefore, we also have to bear its negative consequences. Anyway, accommodating fifty-three refugees in Rottenburg would be a piece of cake.” He even offered to send a bus to Italy to pick them up. Neher’s stance seems to have attracted a lot of local support: this week, he told the German weekly Zeit that when he walks through his town, he is often stopped, because Rottenburg residents want to know when the refugees will arrive and how many of them the town is “allowed” to host.

What explains the magnitude of support for Sea-Watch in Germany? Carola Rackete is part of the answer. For a start, she is comparatively young. Since the emergence of Greta Thunberg and the Fridays for Future movement, young people and their concerns are being taken seriously. To give one other example: the Social Democrats are currently looking for a new party leader, and the most obvious candidate is thirty-year-old Young Socialists chairperson Kevin Kühnert.

For those who have long campaigned for an about-turn in Europe’s approach to forced migration, Rackete is an activist with the necessary street cred. She is principled and determined and, sporting dreadlocks and appearing barefooted in a television interview, she looks every bit like somebody who might otherwise live in a treehouse in the occupied Hambach Forest protesting against open-cut coalmining or demonstrating against the deportation of asylum seekers or disrupting a gathering of Neo-Nazis. No doubt her appearance also helps explain the vitriol reserved for her by far-right trolls.

Moderates who are concerned about German, Italian and European asylum seeker policies but who would never join potentially violent protests can also embrace her because she does not come across as a radical. Contrary to what Salvini has claimed, she is no communist.

Rackete does not let herself be provoked by Salvini. In interviews, she is calm and her words are measured. Talking to German television station ZDF, she declined to comment on Salvini’s attacks on her. “I find it inappropriate to insult others,” she explained. “I like to work with facts. And anyway, as a captain you shouldn’t get excited. At least not in front of others.” In interviews, she presents as a captain: as somebody who is responsible for her crew and for the migrants rescued by them, and who takes that responsibility seriously.

Rackete is also highly articulate and clearly knows what she is talking about: about her ship, the international law of the sea, Europeans’ moral responsibilities, and conditions faced by migrants in Libya. At the same time she claims that she prefers her actions to do the talking for her.

Her arguments are convincing. She is not calling for Europeans’ pity but insists that Sea-Watch is standing up for the rights of forced migrants. A recent article in the online edition of the Bremen daily Weser-Kurier was illustrated by an image of Rackete with a quote from her: “There is a right to be rescued. It’s all about the principle of human rights.”

Commentators in Italy and Germany have likened Rackete to Sophocles’s Antigone: the woman who defies the law of Thebes by deciding to bury her brother Polynices. When brought before Creon, the King of Thebes, Antigone justifies her action by claiming that divine law trumps state law. Rackete too has claimed that she has obeyed one set of laws (namely international law) only to fall foul of another set of laws. But here the parallels end. For Sophocles, Antigone (rather than Polynices) is the key tragic figure of his play. Rackete would probably point out that the real issue is the drowning of migrants rather than her violation of Italian law, and that the conflict between the two sets of laws could be solved if domestic law were adapted to conform with international legal standards.

Finally, Rackete stood up to powerful, unscrupulous and objectionable Matteo Salvini, and did not let him bully her into submission. That explains why her case has attracted more support than that of Pia Klemp, a young woman who captained Sea-Watch 3 (and, before that, the Iuventa, a ship belonging to non-government organisation Jugend Rettet). Like Rackete, Klemp has been charged with people smuggling offences in Italy and, according to her Italian lawyer, she could face “up to twenty years in prison and horrendous fines.” Unlike Rackete, Klemp has been portrayed as Salvini’s victim rather than as an opponent who got the better of him.

The drama around the Sea-Watch 3 has also resonated with Germans for reasons that are unrelated to the attributes of particular individuals. (I discussed some of them in Inside Story a year ago, so I’ll focus on other aspects here.) Over the past decade in particular, the idea has slowly taken hold that non-German residents of Germany enjoy the same rights as citizens. To use the words of Angela Merkel, who ought to be credited with insisting on this idea even when it was unfashionable, “The values and rights of our Basic Law are valid for everyone in this country.”

Once it is accepted that the first line of the constitution’s Article 1, “Die Würde des Menschen ist unantastbar” (human dignity is inviolable) applies to everybody in Germany, then it makes little sense to deny this right to people outside Germany’s borders. An increasing number of Germans believe that the obligation to rescue migrants in the Mediterranean has nothing to do with their particular motivation for migrating or degree of suffering; rather, it’s to do with their being human. This conviction prompts people to attend rallies, donate money for organisations like Sea-Watch, and demand that their local communities commit to accommodating additional refugees.

Also in the mix is a commitment to Europe. When the Spiegel put an image of Carola Rackete on its cover last week, it did so with the headline “Captain Europe.” This should be read as more than a reference to the Captain America superhero movies. Those yearning for another, better Europe in which solidarity is not a hollow term focus on what happens at its borders, because it is there that the idea of Europe has been most severely compromised. As the following episode shows, this is not always made as explicit as it was on the Spiegel cover.

One of the German cities whose council has passed a resolution condemning Italian and European policies is Hildesheim in Lower Saxony. Because it’s the town where I was born, I was interested to find out about the debate surrounding this resolution.

Hildesheim’s councillors voted in August 2018 on a resolution jointly submitted by Social Democrats, Greens and the Left titled “Facilitate and support rescue at sea — fight against the dying in the Mediterranean — accommodate people in distress.” Although the Christian Democrats opposed the resolution on the grounds that these issues were none of the city council’s concern, one Christian Democrat rose to speak in its favour. According to the minutes, “It is true that the council cannot solve all of the world’s problems, such as the persecution of the Rohingya or the poverty of the elderly, and has to concern itself with the problems it has been entrusted with. However, the obstruction of rescue ships is a scandal which needs to be identified also by the Council of Hildesheim.”

This explanation is at once baffling and compelling: baffling because the persecution of Rohingya, on the face of it, is as much an event outside the council’s remit as the deaths at Europe’s borders; compelling because the councillor’s obvious reasoning is that the scandal is European-made, and that implies an obligation to speak up as a European.

The German support for rescue missions in the Mediterranean may also be informed by the experience of the Willkommenskultur (or culture of hospitality) of 2015–16, when many Germans rose to the challenge of accommodating a record number of asylum seekers rather than revert to the fear, if not panic, evoked by a comparable situation in the early 1990s. But I suspect that the safe haven initiatives by German cities and the recognition that human rights don’t end at national borders will prove more significant than the much-discussed Willkommenskultur.

While Carola Rackete is still in hiding, Sea-Watch is sending a new crew to Lampedusa. It is hoping that Italian authorities will release its ship soon, and that it can then return to the waters off the North African coast.

Meanwhile, three other non-government organisations are active in the Mediterranean. Earlier this month, the German organisation Sea-Eye’s ship Alan Kurdi handed over sixty-five rescued migrants to the Maltese authorities; the day after leaving Malta, it then rescued another forty-four migrants and is now looking for a harbour where it can disembark them. Alex, a yacht belonging to the Italian organisation Mediterranea Saving Humans, also defied Salvini’s orders and last week disembarked forty-one migrants in Lampedusa. And the Barcelona-based organisation Proactiva Open Arms is still active but has been threatened by Spanish authorities with fines of up to €900,000 if it continues its rescue mission.

The EU is once again talking about distributing migrants rescued in the Mediterranean among some member states without having to haggle over the quotas each time. But so far these talks, like many similar talks on previous occasions, haven’t had any tangible outcomes.

Gerd Müller’s idea of evacuating migrants from Libya has met with silence both in Brussels and in Berlin. But it may be less far-fetched than it seems. Germany, for one, has been resettling some migrants deported from Libya to Niger: according to unofficial figures, 276 Eritreans and Somalis were resettled in mid October and early December 2018, for example. Thus there is a precedent for another kind of “Libyan solution.”

In the meantime, conditions in Libya could hardly get worse, and the European border in the Mediterranean remains the deadliest border in the world, accounting this year for about half of the world’s border-related deaths. In the first ten days of July, the International Organization for Migration counted eighty-three border deaths in the Mediterranean, while there were seventy-eight in all of June.

When Carola Rackete described the seventeen days it took to find a solution for the people her crew had rescued, she drew attention to the fact that there was a lot of talking — in Rome, in Berlin and in Brussels — but no action. By acting, she exposed the emptiness of the talking. Even Matteo Salvini, who likes to portray himself as a can-do politician but, like Donald Trump, spends most of his time campaigning, was shown to be spouting mere rhetoric. •