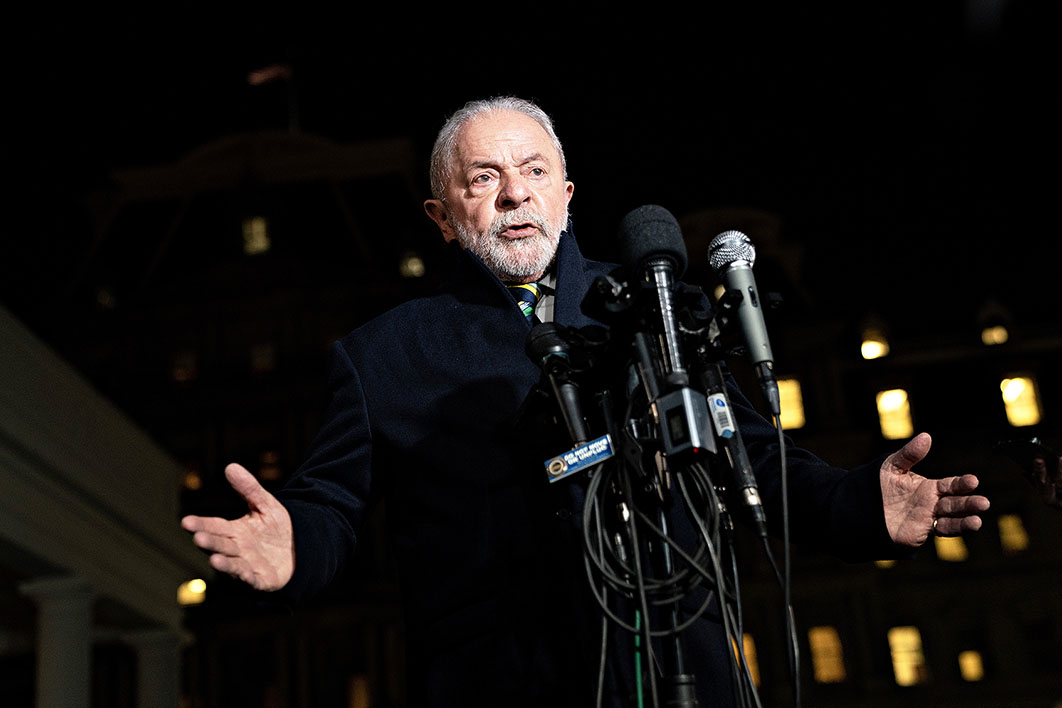

Students of the art of political rowing-back will have recognised a fine example of the genre earlier this week. Brazil’s President Lula declared on Sunday that Vladimir Putin would be welcome at next year’s G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro, and wouldn’t be arrested as a suspected war criminal as Brazil’s membership of the International Criminal Court requires. Indeed, if arresting him was compulsory, Brazil might leave the court. After a domestic and international outcry, on Monday Lula subtly altered his position. Putin would indeed be arrested, he insisted, because Lula took Brazil’s commitment to the ICC very seriously.

The episode rather neatly demonstrated the balancing act Lula is trying to perform on the world stage. He has been assiduously positioning Brazil as an independent global power, seeking to act as a mediator in Ukraine rather than condemning Russia as demanded by the United States and Europe, promoting the non-Western BRICS club of major economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and flying to Cuba to reiterate Brazil’s role as a leader of the G77 grouping of developing countries.

But he has also just signed a joint declaration with the United States proclaiming the G20 group of large economies the principal forum for multilateral diplomacy and declares himself a global champion of democracy, warning of the perils of authoritarian populism promoting racism and civil violence. (Brazil had its own “invasion of Congress” events in January this year when supporters of former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro stormed parliament and the Supreme Court in an attempt to overthrow Lula’s election victory, a deliberate echo of the events of 6 January 2021 in Washington, DC.)

The jury may be out on whether this balancing act can work, but no one could accuse Lula of passivity in foreign policy. In the past few weeks he has attended the Global Financing Pact summit in Paris, the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, the G20 summit in Delhi, the G77 summit in Havana and the UN General Assembly and Climate Ambition and Sustainable Development summits in New York, and convened his own Amazon summit in Brazil’s northeastern city of Belem. This year Brazil chairs the Latin American trade partnership Mercosur. Next year it will hold the presidency of the G20. In 2025 it will lead the BRICS and will also host the critical UN climate summit COP30.

To appreciate what Lula is seeking to achieve from this feverish activity it helps to understand the man. Now seventy-seven, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula” was an early nickname he later formally incorporated into his official name) has not had the usual politician’s life. Born to poor parents who migrated from Brazil’s northeast to São Paulo in search of work, Lula didn’t learn to read until he was ten. Starting out as a metalworker in the automobile industry, he became a trade unionist, was elected leader of the Metalworkers’ Union at the age of thirty, and then led major strikes and democratic protests against Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1970s.

In 1980, increasingly identifying as a socialist — neither a communist nor a moderate social democrat — Lula helped form a new political party, the Workers’ Party. Though he was widely mocked for his poor Portuguese, his electrifying rhetoric and brilliant organising skills marked him out. He was elected to Congress in 1986 and subsequently stood as the party’s presidential candidate three times before finally winning in 2002.

In office, Lula immediately set about fulfilling his election promise to attack poverty, establishing the Bolsa Familia system under which mothers received welfare payments conditional on their children staying in school and being vaccinated. Aided by an economic boom, he raised the minimum wage, and expanded primary education and healthcare. Poverty in Brazil fell by more than a quarter in his first term alone. Re-elected in 2006, he turned his attention to the Amazon, succeeding in slowing deforestation for the first time. Brazil’s economy grew and its public debt fell.

When he left office after two terms in 2010 Lula had popular approval ratings of over 80 per cent and the undying enmity of Brazil’s conservative political elite. When the Trumpian populist Jair Bolsonaro became president in 2016, no one was surprised when he used a compromised judicial system to put Lula in jail.

Defeating Bolsonaro in last year’s election was redemption for Lula. But in a deeply divided country — the parallels with the United States are remarkably close — the margin was tiny: 50.9 per cent versus 49.1 per cent in the run-off vote. In the Brazilian Congress, which he does not control, Lula has had to cobble together an unstable multiparty coalition, making his legislative task much harder this time round.

Nevertheless, he has high ambitions. His Ecological Transformation Plan is meant to be a comprehensive economic strategy aimed at greening the country’s industrial structure. He wants to raise agricultural productivity to expand food production while conserving the country’s abundant natural resources. He has committed to ending hunger by extending Brazil’s welfare system, and to ending the illegal incursions into the Amazon forest by miners and loggers that routinely lead to violence against indigenous people. Deforestation is already down by over 40 per cent in less than a year.

Lula’s remarkable ability to build pragmatic political alliances makes it likely that he will achieve much more of his program than his congressional numbers would suggest. But it is on the world beyond Brazil that Lula’s political gaze is now increasingly fixed.

It is not too much to say that Lula wants to redesign the global order. In his speech to the UN General Assembly this week, Lula railed against the increasing inequality of a global economy in which, as he pointed out, the ten richest billionaires have greater combined wealth than 40 per cent of the world’s population, and 735 million people go hungry. He noted that the richest tenth of the world’s population are responsible for almost half of all carbon emissions, but also insisted that developing countries did not want to follow the same economic model. And he decried the erosion of multilateralism — “the principle of sovereign equality between nations” — in global affairs.

Lula’s rhetoric has always been grandiose, even utopian. But he has a remarkable record of making things happen. At the end of this year’s G20 summit in New Delhi, Lula set out his plans for next year’s presidency. Under Brazil, he said, the G20 would focus on reducing global inequality, poverty and hunger; on making the global growth model more environmentally sustainable, in terms of both climate change and nature conservation; and on reform of the way international institutions are governed.

Because he believes it is what will unlock the others, it is the last of these goals that is really in Lula’s sights. Like almost all leaders from the global South, Lula looks at how multilateral institutions work and sees both historical obsolescence and profound injustice.

Almost all the major institutions of global governance have remained unchanged since they were established at the end of the second world war. Eighty years later, despite new economic and regional powers emerging — notably the European Union, Germany, Japan, India and Brazil — the UN Security Council still has only five permanent members (the United States, Britain, France, Russia and China), the great powers that had prevailed in the war. And the World Bank and International Monetary Fund are still governed by their largest shareholders, an even narrower group of Western countries dominated by the United States and the other economies of the G7 (Germany, France, Britain, Italy, Japan and Canada).

All members of the World Trade Organization have equal decision-making power, but partly for that reason it has increasingly been bypassed in recent years by regional and bilateral trade agreements promoted by the United States, China and the European Union. The world’s premier economic advisory body, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, remains in thrall to the free-market orthodoxies of the Western countries that run it.

And the single most powerful institution in the world economy is arguably the dollar, in which a huge amount of global trade and investment is denominated. But this means much of the world is deeply vulnerable to changes in its value, as the last two years of simultaneously rising dollar and US interest rates have shown. The dollar is not even governed by postwar international arrangements: its master is the US Federal Reserve, whose mandate is entirely focused on the US economy.

Lula wants all this changed. This is why he has loudly pursued the development of the BRICS grouping, even going so far as to suggest that it could seek to replace the dollar as a global trading currency. Lula sees the BRICS as a non-Western power bloc to counter the G7, whose cohesion in the decision-making forums of the G20, World Bank and IMF starkly contrasts with differences among the major countries of the global South.

At its recent summit in South Africa, the BRICS group admitted several new members, including the wealthy and increasingly assertive Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, with the aim of extending its reach and influence. But most Western commentators are dismissive. They note that BRICS, unlike the G7, is made up of countries whose economic and political systems are not only fundamentally different from one another but also subject to major tensions and conflicts, especially in the case of superpower rivals China and India. Nevertheless, it is a signal of Lula’s intent that he wants to strengthen an alternative alliance through which to pursue his reform agenda.

Lula’s public statements on Russia and the war in Ukraine should be seen in this light. Like most countries in the global South, Brazil regards the UN Security Council as the proper arbiter of international conflict. If the Security Council assesses and then condemns one country’s aggression, Brazil will also do so. But it has never done so when the Security Council has not come to a judgement — as in the case of Ukraine, because Russia has exercised its permanent member veto.

Talking to Brazilian foreign policy experts in Brasilia and Rio I detected no illusions about Russia’s responsibility for the war in Ukraine. They note simply that the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, supported by almost all other Western states, was also illegal under UN law. And they observe that the West can apparently find fiscally unconstrained sums of money to defend Ukraine while simultaneously claiming it has no money to expand development aid or climate assistance to the poorest and most vulnerable countries elsewhere in the world. “And what did you do during Covid?” one asked me. “When the world cried out for vaccines, you hoarded even your surplus ones.”

Brazilians are enjoying the country’s new prominence on the global stage. Lula gets notably less criticism for his numerous foreign trips than leaders in most other countries. Along the way, he won’t hesitate to criticise the West for its moral failures. But he will also seize the chance to work with it. “Brazil is back!” the president likes to say. Preparing to assume the chairmanship of the largest powers at the G20, he doesn’t intend to waste the opportunity. •