Thomas De Quincey was a prolific and profligate writer, his Collected Works running to twenty-three volumes. Yet if he is known for anything outside the world of academia it is for one volume, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), his mesmerising account of laudanum addiction. Perhaps not surprisingly, the title of Robert Morrison’s The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey (2009) prioritises that well-known text over its author’s name. Morrison reaches out to modern readers with little sense of De Quincey’s vast output but a possible acquaintance with the founding text of addiction literature.

John Carey called Morrison’s study “astute and revealing,” and it made the shortlist for the James Tait Black Prize, Britain’s longest-running biography award. As it happened, Carey’s own William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies won that year. Revealingly, Carey incorporated Golding’s classic debut novel into his title, suggesting that without overt semaphoring even informed readers might struggle to recall the 1983 Nobel Prize winner.

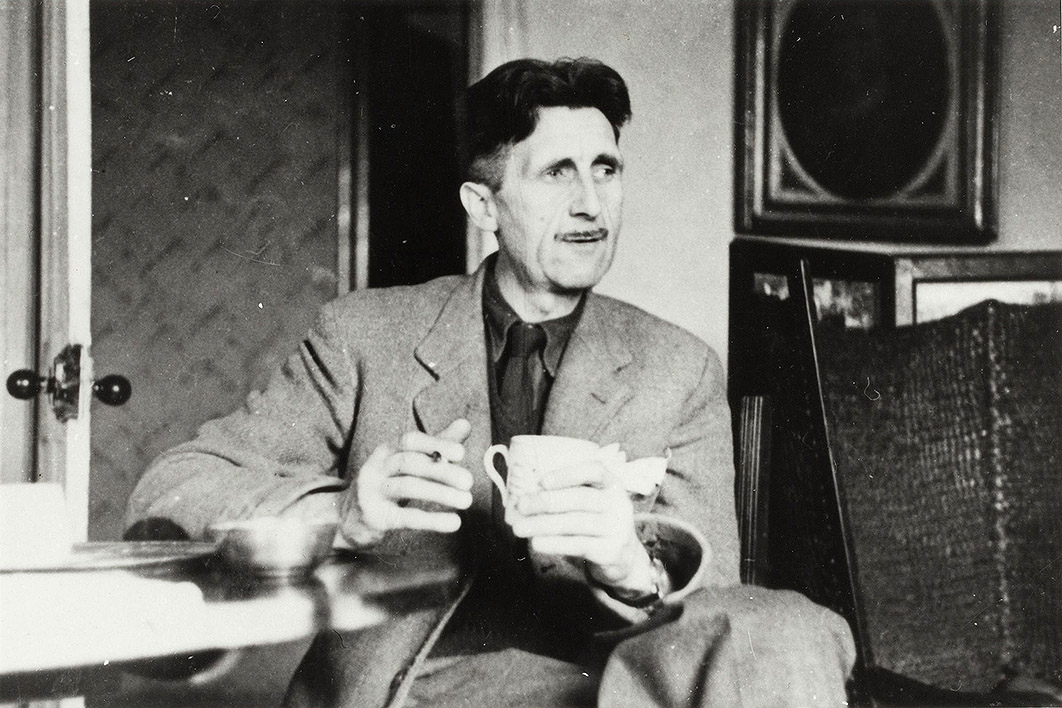

Morrison once told me his publisher had admitted that only four writers in English could be guaranteed a readership sizeable enough to make a biography an attractive business proposition: Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf and George Orwell. Which in part explains why D.J. Taylor’s new biography of Orwell does not come subtitled The Man Who Wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. Orwell needs no prompt. But the subtitle of Taylor’s Orwell: The New Life is revealing, for his own Orwell: The Life was published in 2003. And that raises the question: how is Taylor’s new life of Orwell “new”?

Orwell hoped no biography of him would be written, but the renown of Nineteen Eighty-Four and the enduring appeal of Animal Farm made that unlikely. He died in 1950 at the age of forty-six, but nearly three-quarters of a century on he is regularly quoted (and sometimes misquoted) by journalists and politicians, and taught in schools, a writer whose impact on language and the public imagination extends to people who have never read him.

His early death meant he never truly experienced that celebrity. Homage to Catalonia, for example, now understood as a classic account of the Spanish civil war, sold fewer than 700 copies in his lifetime. And while he came to be acknowledged as a great essayist, most of his short works first appeared in obscure journals with paltry readerships.

In many ways, though, he is a biographer’s dream, a quirky figure with a sharp intelligence and sharper opinions who lived a brief, eventful life in troubled times. The years between 1903 and 1950 witnessed two world wars, the British Empire’s decline, the rise (and sometimes fall) of left- and right-wing totalitarian regimes, a global depression, the Spanish civil war in which he fought, and the cold war, which he is credited with naming in his 1945 essay “You and the Atom Bomb.” Even better for the biographer trying to construct the narrative arc of his life, Nineteen Eighty-Four was published barely six months before his death. To add to the pathos, he died alone at night in hospital, haemorrhaging from the effects of the tuberculosis that haunted his life.

Born Eric Blair in India to parents who were minor figures in the Anglo-Indian community administering that part of the Empire, he was educated at an English prep school he later eviscerated in “Such, Such Were the Joys,” a memoir so libellous it was not published in his lifetime. He then seemed to consciously squander the prestigious and highly competitive King’s Scholarship he had won to Eton, rejecting the route to Oxbridge taken by contemporaries such as Cyril Connolly and Steven Runciman, later a renowned classicist.

Instead, he worked for five years in Burma with the Imperial Police before returning to England, then spent the next half-decade trying unsuccessfully to write novels in Paris. (He managed only a few articles in Parisian newspapers — in French.) He worked there as a kitchen hand and in England as a teacher, living for brief periods among tramps and itinerant rural workers and mooching off his bemused parents, by now in retirement in the staid English town of Southwold.

He used much of this experience in articles and essays, novels and documentaries. In some sense he was his own biographer, although critics and actual biographers sometimes struggle to distinguish fact from fiction. Did he witness “a hanging” — the title of his first great essay — in Burma? Or, given its undertones of Somerset Maugham, is that work actually a short story? Or some hybrid? Is another essay, “Shooting an Elephant,” an eyewitness account or a crafted “sketch” (the term Orwell used for it) using a first-person narrator for dramatic effect?

Taylor thinks treating both as “straightforward pieces of autobiography” is “a mistake.” “A Hanging” was published in 1933 under the name Eric Blair, while “Shooting an Elephant” appeared in 1936 as the work of “George Orwell,” a pen name that first appears in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). Biographers suggest that Blair adopted it to avoid his parents being publicly embarrassed by the book’s squalid details. “George Orwell” was only one of four names he suggested to his agent, two others being the uninspired “Kenneth Miles” and the laughable “H. Lewis Always.” The published title was also a late choice. Potentially, Eric Blair’s first book might have been published as The Lady Poverty, by H. Lewis Always. Thankfully, Down and Out in Paris and London and George Orwell prevailed.

Writing by Eric Blair continued into 1935, and the BBC hired Orwell under his real name during the second world war, but critics often see the adoption of the pseudonym as part of an ongoing psychological and political evolution. In this reading, Blair sheds many of the trappings of middle-class life, though the accent honed at Eton never leaves him and he might dress formally for dinner. He adopts the somewhat ascetic, combative and consciously quirky persona of Orwell, dressing with a provocative déclassé dowdiness and rather clumsily adopting working-class mannerisms such as hand-rolling cigarettes and drinking tea from a saucer.

All this suggests some level of inauthenticity, and Taylor repeatedly points to Orwell consciously fashioning a persona: “as well as being a biography,” he writes, “what follows is, ultimately, a study of Orwell’s personal myth, what might be called the difference between the kind of person he was and the kind of person he imagined himself to be.”

We might read this as less duplicitous than aspirational, but the undoubted tensions between middle-class and working-class perspectives finds literary form in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). This bifurcated study begins with Orwell’s report of conditions in working-class sections of northern England, a section meant to shock and educate middle-class socialists in southern England likely to read it. The book’s second half presents Orwell’s account of his upbringing and political development, a precursor to his idiosyncratic argument for an English socialism, shorn of Soviet affectations, in which the middle class merges in solidarity with the working class.

Homage to Catalonia road-tests Orwell’s developing socialist views in extreme circumstances, while Coming Up for Air (1939) tracks with wry affection the journey of a nostalgic Everyman who yearns for a past now long gone but senses impending war. The transformation from 1933’s Eric Blair to 1939’s George Orwell is dramatic, but had he written nothing after 1939 he would have at best been a literary footnote. Instead, he writes Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), two of literature’s greatest political fictions.

Without these late works, Orwell would hardly warrant one biography, let alone the half a dozen that have appeared from Bernard Crick’s 1980 study to Taylor’s latest life. But that simple sequence conceals a fraught narrative. Orwell’s second wife Sonia knee-capped Peter Stansky and William Abrahams’s early biographically based studies, The Unknown Orwell and Orwell: The Transformation, denying them the right to quote from Orwell’s work. She also floated the idea that Orwell’s friend Malcolm Muggeridge would write the first authorised biography, possibly to put off other potential candidates. Then, after selecting Crick, a political scientist, she disavowed his study as too dull, trying unsuccessfully to break the book contract. Sonia Orwell died before Crick’s account of Orwell was published to general acclaim — Orwell’s friend, the writer Julian Symons, called it the “definitive biography.”

When a study authorised by the Orwell Estate eventually did appear, Michael Shelden’s Orwell: The Authorised Biography (1991) took pains to dismiss Crick’s biography as a collection of facts that failed to illuminate Orwell’s character and motivations. (Crick returned fire in the 1995 reprint of his work.) Shelden’s study reflects his training as a literary scholar interested in character and motivation, while Crick adopts a more objective social science approach.

Jeffrey Meyers’s Orwell: Wintry Conscience of a Generation (2000) seeks to portray Orwell as a more problematic individual, a man with “a noble character, but [who] was also violent, capable of cruelty, tormented by guilt, masochistically self-punishing, sometimes suicidal.” Neither Crick nor Shelden paint Orwell as saintly, but Meyers strives to present him as a dark figure, without fundamentally changing the narrative outline of his life.

Biographers from Meyers on have enjoyed access to The Complete Works of George Orwell (1998), a twenty-volume set brilliantly edited by Peter Davison that presented not only Orwell’s published work but also masses of previously unpublished letters and documents. This and other material made available in the ever-expanding Orwell Archive at University College London afford and sometimes demand more recent reappraisals.

The centenary of his birth in 2003 prompted two more biographies, Gordon Bowker’s George Orwell and Taylor’s Orwell: The Life, proof that publishers saw an audience large enough to justify concurrent studies. Bowker continued the desanctification of Orwell, accepting him as a “writer of great power and imagination” but making much of what he saw as his subject’s deceptive character, infidelities and chauvinism. He declares that the “main thrust” of his book is to “reach down as far as possible to the roots” of Orwell’s emotional life,” to get “as close as possible to the dark sources mirrored in his work.”

Taylor’s biography is less lurid, but he too exposes Orwell’s less-appealing qualities. And he intersperses the chronological biographical narrative with short essays on topics such as “Orwell and the Jews,” examining Orwell’s problematically complex attitudes, or “Orwell’s paranoia,” about “malign exterior forces that he suspected of interfering in his and other people’s lives.”

Like Bowker, Taylor understands Orwell as a great writer — both come to praise Orwell rather than to bury him — but he too acknowledges substantial personal flaws. Taylor even includes a short “case against” Orwell, written in the persona of a Marxist critic who claims that “as a novelist, Orwell scarcely begins to exist” and declares him a “hopelessly naïve” political thinker. Taylor himself is far more positive.

Unusually, both of Orwell’s wives have merited biographies. The title of Hilary Spurling’s The Girl from the Fiction Department: A Portrait of Sonia Orwell (2002) overtly connects Sonia Orwell with Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Julia, while Sylvia Topp’s Eileen: The Making of George Orwell (2020) argues for the influence of his first wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, on his life and writing. Anna Funder’s Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, published this month (and reviewed for Inside Story by Patrick Mullins), advances that general case, presenting a complex mix of critique and life writing that faults Orwell himself for largely “erasing” Eileen from his writing and accuses previous Orwell biographers (all male) of failing to pay due respect to Eileen’s intellect and emotional support, as well as to the “free labour” that allowed Orwell to pursue his life as a writer at the expense of her own considerable abilities and ambitions.

Funder’s fictionalised vignettes, based on known facts and exchanges of letters with Eileen’s female friends, reposition her centrestage. All this takes place within a larger investigation of “wifedom,” the general condition Funder maintains continues to require wives (including herself) to operate within patriarchal power arrangements detrimental to their own flourishing. Provocative, fluent and energetic, Wifedom will activate lively debate among Orwell scholars and the general readers interested in Orwell and his milieu.

Which brings us to Taylor’s New Life. As with Funder, Taylor has access to new information unknown to earlier biographers, including Eileen’s often deeply personal letters to her friend Norah Myles, made public in 2005, which detail her life with Orwell from 1938 to 1941. Recently uncovered caches of letters also illuminate Orwell’s already known relationships with two women he pursued romantically before and after his marriage to Eileen.

Revelations have also emerged about Eric Blair’s problematic last meeting with his teenage love, Jacintha Buddicom, an event that might count as sexual assault. And Taylor assigns much greater importance to Orwell’s “ever-supportive Aunt Nellie,” who proved a key benefactor. Nellie’s living in Paris offered him literary and political connections in that city; her friends Francis and Myfanwy Westrope ran the bookshop where Orwell worked in the early 1930s; Nellie secured the spartan cottage Orwell and Eileen lived in through much of the late 1930s.

Women play a far more significant role in The New Life than in Taylor’s earlier book, so that Norah Myles, who does not appear at all in The Life, is referenced more than twenty times in the recent work, part of a more extensive and nuanced account of Eileen’s life and friends. Taylor also accepts Robert Colls’s criticism in George Orwell: English Rebel (2013) that Orwell’s depiction of the working class in The Road to Wigan Pier effaces the vitality of working-class life. Integrating these and other pieces of information and scholarship adds colour and shade to the image Taylor previously depicted, without changing the outline.

Taylor also deals with the relative paucity of primary information about key sections of Orwell’s early life, particularly at Eton and in Burma. All biographies are complex weaves of available evidence and interpretation, but how to proceed if little evidence exists? Michael Shelden, for example, took Orwell’s essay about prep school, “Such, Such Were the Joys,” almost as documentary, even though it was written when Orwell was in his forties and many of his contemporaries thought it exaggerated.

If Shelden accepted the essay too easily as fact, at least it was written by Orwell himself. Taylor at times adopts an odder tactic, at one point deploying the novel Decent Fellows by a rough contemporary of Orwell’s at Eton, John Heygate, to convey a sense of the school a decade earlier. Taylor’s claim that “all this sheds a fascinating light on Orwell’s time at Eton” seems a stretch. And on the question of whether Orwell saw a man hanged in Burma, Taylor connects Orwell’s essay to Thackeray’s 1840 “Going to See a Man Hanged” claiming that the later narrative “could not have been written in quite the same way without the ghostly presence” of Thackeray’s account. This claim, simultaneously large and odd, is somewhat undermined by the fact that The Complete Works of George Orwell makes no mention of Thackeray’s piece.

Even the best real detectives (as opposed to the fictional ones) must deal with the reality that sometimes there is no evidence to be found, and Taylor is honest enough to admit more than once that we simply do not or cannot know. At other times, though, he uses questions to generate potential answers, so that in a late “Interlude” titled “Orwell and his World,” he asks: “Some basic behavioural questions: What was Orwell like? How did he seem? If you were in a room with him, how might he conduct himself and what would you talk about?”

This is a little too close to “showing your workings,” an unnecessary act given the impressive amount of detail Taylor fashions into a coherent and insightful character study. He also retains from his earlier biography the two- or three-page essays on topics he deems worth individual attention. Some are only cursorily rewritten, while new ones are added: “Orwell and the Working Classes” or “Orwell and the ‘Nancy Boys.’” The latter begins with the terrible line “Orwell’s dislike of homosexuals follows him through his work like the clang of a medieval leper bell.” While the topic itself is significant, the dislocation of the narrative that this and similar pieces effect is heightened by its coming immediately after a chapter ending with Eileen’s death during an operation for uterine tumours; the juxtaposition is jarring.

For all this, Taylor assembles a wealth of information, some of it new, much of it intelligently reinterpreted, into what can justifiably be claimed as a “new” biography based on decades of close attention to Orwell’s life and mythology. The occasional medieval leper bell apart, he writes with a fluency that injects the narrative with vitality and significance. The New Life is a knowing biography, incorporating changes and advances in our knowledge and assessment of Orwell without being modish or attempting to defend the indefensible (or at least reprehensible) aspects of his life.

Almost alone among his contemporaries Orwell can still attract a sizeable new audience. W.H. Auden and Evelyn Waugh are still lauded, but they seem figures from a past that is recognisable as the past. As proof of Orwell’s status as a still-relevant writer, at least five books about him have appeared or will appear in 2023: Taylor’s biography; Peter Stansky’s The Socialist Patriot: George Orwell and War; Glenn Burgess’s Orwell’s Perverse Humanity; Masha Karp’s George Orwell and Russia; and Peter Barry’s forthcoming George Orwell: The Ethics of Equality. To which we might add Anna Funder’s Orwell-adjacent Wifedom.

Have we hit peak Orwell? Perhaps. But just as the election of Donald Trump in 2016 rocketed Nineteen Eighty-Four back to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, so the prospect of a second Trump presidency suggests that Orwell might again speak to a new set of readers. To this we can add the menace of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and their abominable clones. The man whose writing spawned the adjective “Orwellian” seems unlikely to go out of fashion. •

Orwell: A New Life

By D.J. Taylor | Little, Brown | $34.99 | 496 pages