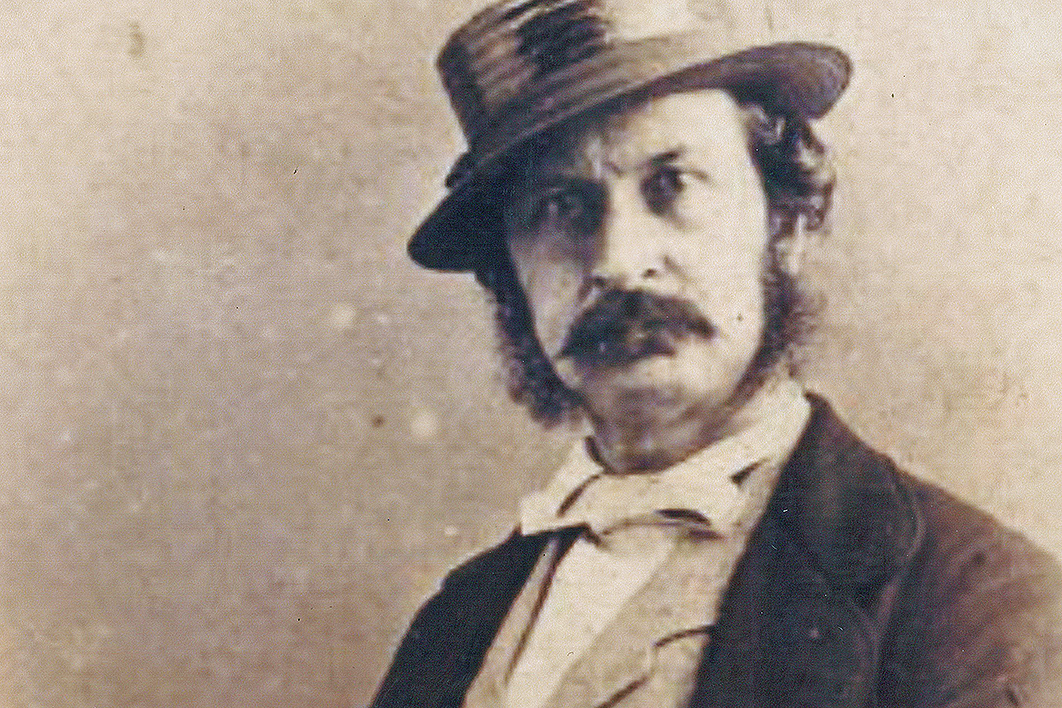

Renowned as a journalist and “eminently unconventional character,” English-born writer John Stanley James – “the Vagabond” – wrote prolifically about life in Australia in the 1870s and 80s. An expanded selection of his journalism, Papers, edited by Michael Cannon, has been published this month by Monash University Publishing. In this extract from an article published in the Melbourne Argus on 27 May 1876, the Vagabond visits the city’s sixpenny restaurants. (The original spelling and punctuation have been retained.)

Most men have to suffer a perpetual combat between their tastes and their exchequer. This is daily brought home to them in the satisfaction of their appetites. Where one has a soul for turtle and ortolans, it is hard to descend to sausages. To feel that a palate educated to appreciate caviare should be condemned to boiled ling in a sixpenny restaurant – what an indignity! There you feed like the beasts of the field: it is a mere question of supporting nature. In another sphere one dines, which is a fine art not thoroughly understood by the common herd, and the grossness of feeding is relieved by the poetry of companionship and association.

Happily, I have been accustomed to rough it in many parts of the world. I glory in a good dinner, but can eat bread and cheese with an appetite; and so one morning I felt no very great repugnance at the fact of having to make a meagre breakfast, which was forced upon me by the unsatisfactory state of my finances. The day before, I had migrated from a certain hotel where I paid ten shillings a day (very cheap, too, according to London scale) to a small apartment in the suburbs, for which I paid five shillings a week. (In London it would be double.) I had sallied down town with the intention of making a cheap breakfast, and had a shilling in my pocket devoted to that purpose. Although I had been some months in Melbourne, and was aware that the necessities of life were very cheap here, I really had no thought that a breakfast could be got for sixpence. The idea seemed ridiculous, as sixpence appeared to me, up to that time, to be the lowest coin in circulation. I avoided the main thoroughfares, and at last entered a small restaurant in one of the bye streets. “Breakfast, sir,” said the Irish waitress, “chops, steaks, sausages, fried fish, dry hash”—. “Stop,” I cried, aghast at this list of luxuries, “I will have a cup of tea and some bread and butter.” “What else, sir? there’s nice steak this morning.” “How much is a steak?” I asked, bent on economy. “Sixpence, sir.” “And the tea, and bread and butter?” “All sixpence.”

“Bring me a steak, then,” I said; concluding that I had fully mortgaged my shilling. I was then supplied with a small steak, a roll, and cup of tea, which breakfast I humbly ate with a good appetite. When I had finished I rose, and putting my hand in my pocket, “How much?” I asked, grandly, and preparing to fling down my shilling as if I had hundreds at the back of it. “Sixpence for breakfast, thank you, sir;” and I left amazed at the fact of having discovered the cheapest meal in the world. The dinner was even a greater surprise to me. That I could obtain soup, meat, and pastry (no matter of what quality) for the ridiculously small sum of sixpence was a revelation of inestimable value.

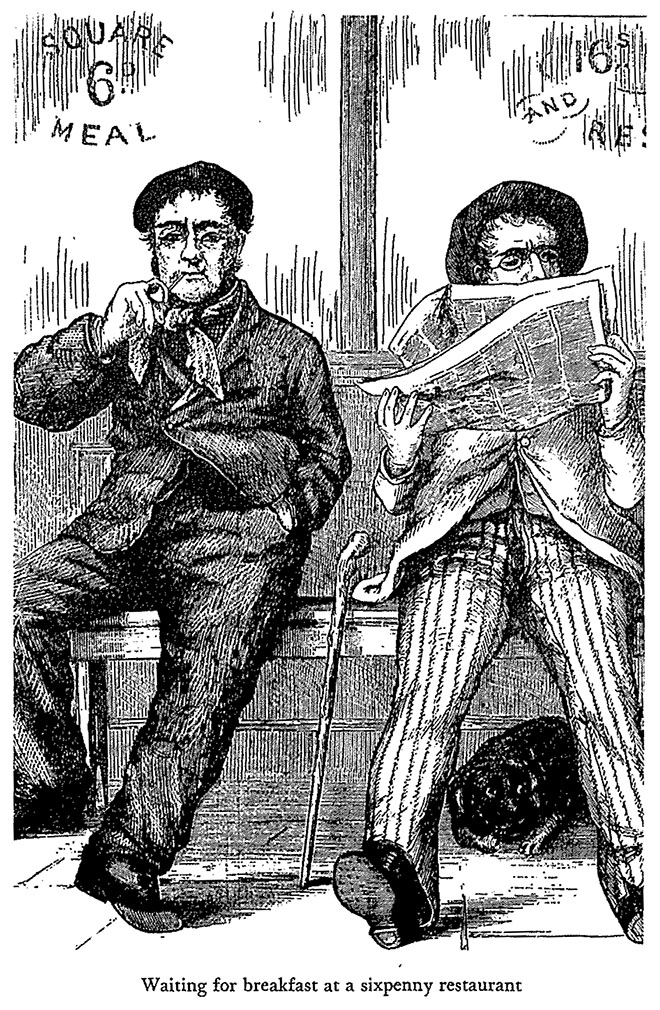

“In essentials they are all much alike.“ Sketch from Illustrated Australian News, 21 December 1881

After the first day I gathered courage, and have since made a tour through most of the cheap restaurants. In essentials they are all much alike. The dishes appear to be stereotyped, and the cooking is much the same in all. There are generally, and especially in the summer, more flies in the dishes than refined prejudices might fancy. The sausages in all are bags of mystery, and the enormous consumption of these is a convincing proof that faith is strong in the colonies. The stews, which are mostly served at supper time, are not equal to the pot au feu of the French peasant, although the ingredients are as miscellaneous. Stewed lamb is a dish often on the supper bill of fare. I wondered for a long time how this was, as lamb is seldom to be had for dinner, till at last I discovered that the multiplicity of dishes consisted chiefly in the names. “Stewed lamb,” with a little curry stirred on the plate, became “curried mutton;” or, with the addition of a few slices of carrot, was “haricot mutton;” or, again, with a few boiled potatoes mashed in, was “Irish stew.” Thus, a smart cook will supply a dozen dishes from one base. Rabbit pie and fish are considered extra luxuries, and are generally announced by placards in the windows. What strikes an Englishman as very strange is the fact of eggs being so dear here. These, boiled or poached, are charged 9d. Fowl or chicken is absent from the menu of the ordinary sixpenny restaurant; but at some they are to be had for one shilling. It seems to me that one of the best speculations untouched would be a large poultry farm in the neighbourhood of Melbourne.

Sixpenny restaurants vary a good deal in style. There are some in the principal thoroughfares which shine with plate-glass, white linen, and pretty waiter girls. But all this extra display, and the cost of the handbills, which are so freely circulated, causes perceptible diminution in the quantity or quality of the viands. The places where one really feeds best are the smaller restaurants, kept by married couples, who do the cooking themselves. At many of these places the proprietors often work very hard, and are not by any means making rapid fortunes. These are chiefly patronized by working men, who take their dinners there. At one o’clock you will see a tremendous rush, every seat at the little tables being occupied. If one has catholic ideas on the subject of dirty hands, it is amusing to sit down with the crowd and watch the different modes of eating. The waiters are for some twenty minutes under a pressure of orders enough to tire out the intellect of most men. The habitués seem to strive to get done first, and he who sits nearest the door may order his “corned beef and cabbage” a dozen times, on each occasion it being captured en route as “my order.” The great appetites of apprentice boys are something fearful to behold, the soup, steak-pudding, and piles of cabbage and potatoes being assimilated by the consumption of half a loaf of bread. After watching the performance of half a dozen of these embryo “sons of toil,” you feel certain that the proprietor of the restaurant must be bankrupt on the morrow. A few quiet individuals generally dine after the one o’clock rush is over, and the same number may be seen at supper at seven o’clock, when they will have a chat together. At the restaurant I frequented there was a strange mixture. A negro gentleman from Jamaica, a noted politician in the Yankee sense of the word, who should have emigrated to the Southern States and got into office, instead of wasting his time here, where he is not believed in. A Frenchman, from the Mauritius. Several sons of the sod of various degrees of station and intellect, but mostly banded together under Holy Church in hatred of the Sassenach. A Birmingham mechanic, the best dressed man of the lot, bright, shrewd, and a liberal and freetrader of the John Bright pattern. A stray Chinaman, who is the only epicure, as he grumbles always at the quality of his “loast beef” or “cheak and lonions.” A hawker, Hibernian, who orates on every subject. A young man of considerable self-assurance, who was an officer in the Southern army during the American war, and is fond of “blowing thereon.” A blind beggar, often drunk, who sits near the door. A strange mixture this, truly, but really more interesting than the guests at many a first-class table d’hôte. The blind beggar is a character, not over cleanly certainly, but the presence of this Lazarus at the gate does not affect our appetites. The room is a long one, and he is afar off. Barring his real or simulated blindness, he reminds me of the beggar in Tom Burke of Ours. He seems the sort of man to sing a seditious song and humbug a jury. On one occasion he distinguished himself greatly amongst his compatriots by offering to raise a subscription to buy Signor Ricciotti Garibaldi a rope to send to his father… Now and then a poor vagrant creeps quietly in, and, taking the lowest seat, enjoys a good meal. All through the day miserable-looking dogs, who, according to the Pythagorean doctrine, are transformed vagrants, steal in, and, gliding underneath the tables, pick up scraps and bones. The kind-hearted proprietor often feeds them, and if the dogs fare as well at every restaurant in Melbourne, it is no wonder we see so many ownerless curs.

Restaurant waiters are not a class. They are refugees from all classes. One or two establishments employ young girls, who certainly are efficient in enticing you to order beer, when a bar-room is an adjunct of the place; but men waiters are the rule. They are of all trades and professions – new chums and old hands. Now and then you meet with a smart youth, who knows his business. Generally he has graduated at some good hotel, and drink or misfortune has condemned him to this. The cooks at these places, too, are mostly men who have begun with making damper. I know one man, however, thoroughly educated, who has passed years of his life in Parisian society, and is heir to £5,000 a year, who is now a cook in a restaurant. Some taverns set up as rivals to the restaurants, by giving “hot lunches, with pint of ale, from twelve to two daily, for sixpence.” The lunch is chiefly a plate of corned beef and potatoes, and instead of a pint of small beer you can compromise for a glass of the best. You get, altogether, about half the amount of food you would at a sixpenny dinner. Still these lunches are very cheap, and are much affected by young clerks, who may be hard up or economical, and who often steal in the back way to these places. Others, too proud, will spend sixpence in beer at an hotel bar, nibbling as much of the “free lunch”… as their shame will allow them. It would be far better for them if they would put their dignity on one side, and take a dinner in a sixpenny restaurant, which, up to this time, I consider to be the most wonderful example of Victorian progress and prosperity which I have met with. •

The Vagabond Papers is edited by Michael Cannon with contributions by Robert G. Flippen and Willa McDonald.

• Michael Cannon and Robert Flippen discussed the book with Thornton McCamish at the State Library of Victoria on 15 September 2016. View the YouTube recording here.