Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry

By B.S. Johnson | Picador | $22.99

BRACHYUREATE, sufflamination, helminthoid, vermifuge. Or, best of all, exeleutherostomise. These words, and others similarly obscure, are dotted through B.S. Johnson’s 1973 novel Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, impeding the readerly flow. Sufflaminating it, in fact. What to do? Look it up, and find yourself heading off at a tangent that may or may not bring you back to the novel? Or, to use a phrase that, in various versions and permutations, Johnson was fond of, “go on to the end,” resisting the temptation of these distracting pathways? It is a very contemporary dilemma, one that now confronts us daily, in the guise of embedded links that as likely as not will lure us off to another screen, never to return.

Johnson foreshadowed a world – ours, in fact – in which information is infinitely accessible and infinitely seductive, there to be pursued for its own sake and for the brief satisfaction of knowing. “The exact height of Claremont Square escapes me for the moment,” says the narrator of Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, “though I could look it up.” And he does, leaving a blank space within the surrounding text to indicate that he is off somewhere, looking it up. We learn, as a result, that Islington’s Claremont Square is a hundred and fifteen feet above sea level, “but of course that is not really relevant for our purposes.”

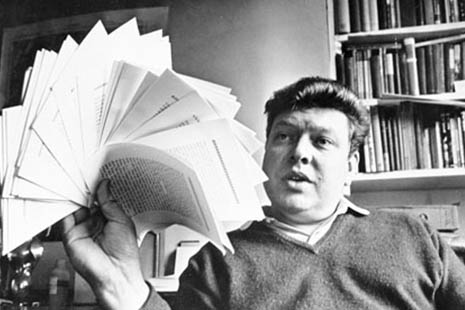

B.S. Johnson is the best remembered of a group of British novelists who were writing in the 1960s and 70s – “we do not form a ‘school,’” said Johnson at the time, “the things we have in common are mostly generalities” – and who consciously played with and manipulated the form of the novel, rejecting what Johnson called the kind of “neo-Dickensian” fiction that continued to rely on “the crutch of storytelling.” Other names – Ann Quin, Rosalind Belben, Alan Burn, Eva Figes and the dauntingly inventive Christine Brooke-Rose, among others – are less well-known today, even though several of them have continued to publish into the twenty-first century and to receive admiring critical notices. (As Jonathan Coe puts it in his biography of Johnson, Like a Fiery Elephant, “they were not as good at putting their names about.”)

While there are signs that interest is reviving in these writers, they remain very much associated with a particular period, the late 60s and early 70s, when Johnson, extraordinarily prolific in journalism, drama, film and television as well as in fiction, was leading the experimental charge. (“I object to the word ‘experimental,’” he said, partly it seems because it suggested unsuccessful or half-baked.) When he died, by his own hand, in November 1973, shortly after the publication of Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, it seemed that a line had been drawn under the cause of formal invention, and that the realism – the “story-telling” – that Johnson so vocally despised was set to regain the upper hand, if indeed it had ever lost it. In 2013, on the fortieth anniversary of his death, with the re-issue by Picador of several of his novels and a selection of his prose and drama, as well as a compilation by the British Film Institute of “the films of B.S. Johnson” entitled You’re Human Like the Rest of Them, there is an opportunity to look again at works with an oddly anticipatory quality.

Johnson can be very funny, in ways that link him as much to the new humour of the late 60s and early 70s – in particular Monty Python – as to his fellow experimental novelists. In Python mode, the humour can range from cringe-making one-liners to the inherent comedy of a basic, underlying premise. Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry is founded on such a premise, and it is a brilliant one. Christie, a young accountant, determines to apply the principles of double-entry bookkeeping not only to his work but to his life. This idea, of applying more widely the “sublime symmetry of Double-Entry,” comes to him in a flash of inspiration when, on his way home from work, he finds that his path is dictated by the presence of a giant, “no doubt speculative,” office block. In double-entry terms, this constitutes a debit to Christie for the offence received, and a credit to the office block for offence given. The books must be balanced. Christie “stopped and took a coin from his pocket and, keeping close to the wall whilst holding the coin down at arms length, he scratched an unsightly line about a yard long into the blackened portland stone facing of the office block.” Christie is credited; the world of business, as represented by the office block, is debited. “Account settled!”

As the novel progresses, the offences against him mount, as does Christie’s unquenchable anger, and so his “balancing” actions grow more extravagant and more extreme. Soon there are bodies everywhere. The outlines of a comedy, a political thriller, a love story, and a human tragedy are all contained within a novel that is barely 20,000 words long. “Who wants long novels, anyway?” asks Christie. Who wants description, or character, or plot? “Physical descriptions are rarely of value in a novel,” announces the narrator pompously. We are constantly being reminded that it is a novel that we are reading, that a writer is making all this up, that Christie does not exist other than in the mind of the novelist. It is quite an achievement therefore that, with all these reminders of the artificiality of what we are reading, Christie should emerge as such a powerful, and powerfully affecting, character. Johnson understands the paradox and, typically, plays with it, reminding us that he controls Christie’s fate and that, 150 pages in, he is keen to wrap things, and Christie, up.

For all Johnson’s railing against character and plot and the trappings of the traditional novel – why write that kind of novel, he asks, when it’s the sort of thing that can be done much more effectively on television? – he has a very traditional approach to the standing and authority of the writer. Not for him the participatory reader, the postmodern co-creator who brings himself or herself to the text. On the contrary, says Johnson in his combative introduction to the collection of shorter pieces Aren’t You Rather Young to be Writing Your Memoirs? (1973), “I want my ideas to be expressed so precisely that the very minimum of room for interpretation is left.” He goes on to issue a challenge: if a reader “wants to impose his own imagination,” says Johnson bluffly, “let him write his own books.” It is a challenge which, in the intervening years since 1973, many people have taken up; writing their own books, keeping their own web journals, taking their own photographs or making their own films, and in the process significantly complicating the relationship between writer and reader, creator and consumer. It is not the kind of relationship that Johnson is likely to have found comfortable or congenial.

Johnson was able to anticipate the rise of technology and the dangers inherent in the anonymity it confers. He detected too the essential fault lines inherent in the worlds of banking and business that have since become so glaring. (“Despite the modernity of computer-based accounts,” Christie observes sardonically, “the original investment in mahogany, marble and brass had been so great as to make it impossible to sweep it away and think about banking all over again.”) He also anticipated something else that the internet culture, a culture that he did not live to see, has fostered and encouraged; the rise and rise of anger and grievance. There is something very modern about Christie’s anger, and his escalating demands for recompense for all the wrongs – the debits – he is forced to incur. The world is out to get him and he must fight back, even though the world will win in the end. •