Tiberius with a Telephone: The Life and Stories of William McMahon

By Patrick Mullins | Scribe Publications | $59.99 | 784 pages

William McMahon was the twentieth person to hold the office of prime minister of Australia, a position he held for twenty-one months. Whether he was the worst-ever occupant of that office is a matter of some debate. His government managed some significant achievements, but they tend to be overshadowed by its leader’s character faults.

“I confess to a dislike of McMahon,” wrote a fellow senior minister, Paul Hasluck, in 1968, in a profile that only became public almost thirty years later:

The longer one is associated with him the deeper the contempt for him grows and I find it hard to allow him any merit. Disloyal, devious, dishonest, untrustworthy, petty, cowardly — all these adjectives have been weighed by me and I could not in truth modify or reduce any one of them in its application to McMahon. I find him a contemptible creature…

And later:

He lost the good opinion of those with whom he was closely associated in politics for very simple reasons. He was disloyal and he could not be trusted and he worked for his own advancement by trying to destroy the reputation of his rivals. He gave away cabinet secrets, sometimes out of vanity and sometimes corruptly in order to buy favours for himself from the press or to injure his colleagues. He was a habitual liar and also a man who lied by calculation about other people and about himself.

Hasluck, it must be said, had been defeated by McMahon in a ballot for the deputy leadership of the Liberal Party when Sir Robert Menzies retired in 1966. But his contempt for McMahon was recorded in other notes he made much earlier than that. His assessment of McMahon did not change when later, as governor-general, he had to deal with Prime Minister McMahon.

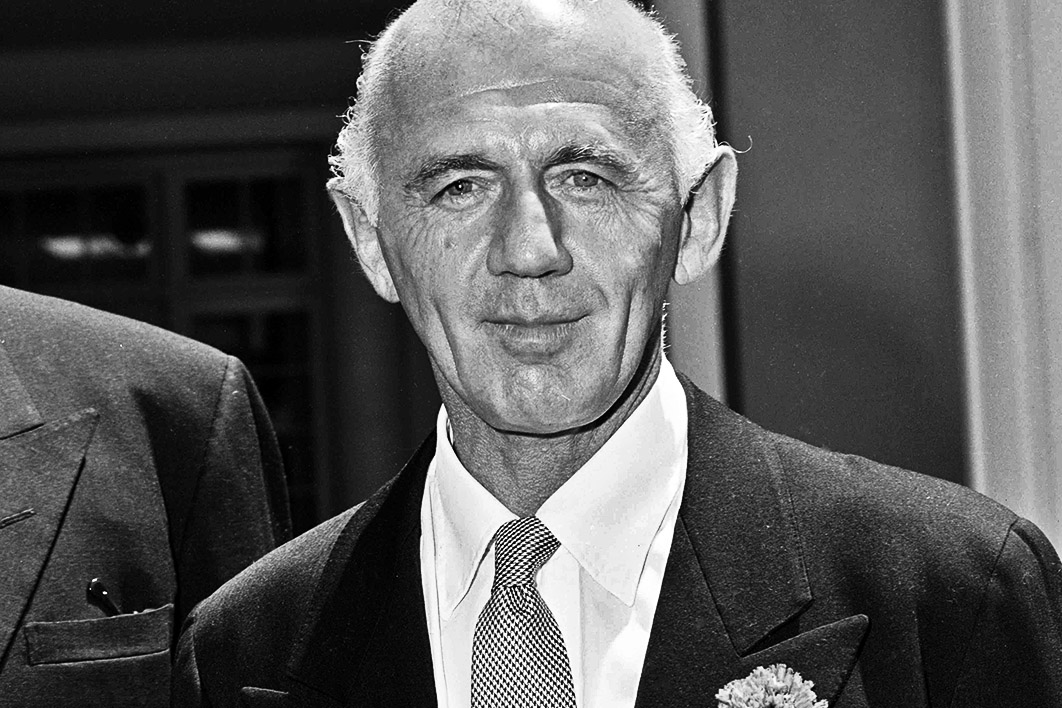

“I find it hard to allow him any merit”: McMahon with his cabinet colleague Paul Hasluck (left) at the swearing-in of the McMahon ministry, 22 March 1971. National Archives of Australia, A1200, L94878

There is no evidence that any of the other Liberal MPs who were McMahon’s contemporaries had a high opinion of him. Yet they chose him to succeed John Gorton as prime minister in 1971. Just how that came about has been the subject of a number of books and many articles, but this is the most detailed investigation and explanation of what happened.

Any recounting of his stories and any judgement on his political life would inevitably reflect badly on McMahon, his political career and his place in Australia’s history. So it’s not surprising that his family did not cooperate with the author of this first major account of his life, and denied author Patrick Mullins access to his voluminous papers.

But Mullins overcame the boycott. He indirectly gained access to crucial parts of the contents of twenty-seven filing cabinets “stuffed full” of the papers McMahon had originally deposited with the National Library. Mullins managed to do this at one remove, using diary notes and other material accumulated by journalist David Bowman, who at one stage was hired by McMahon to edit (and make publishable) the manuscript of his autobiography — a task Bowman quickly realised would require him to become a ghostwriter. He was very well qualified for the job: he had been managing editor of the Canberra Times and had then held senior editorial positions at the Sydney Morning Herald when McMahon was working his way through to the top of the Liberal government.

“When I publish my autobiography and tell the things I had to put up with,” McMahon had boasted, “none of you will believe it.” One of the challenges for the author lay in that last phrase. Would anything McMahon wrote be credible? As Bowman was soon to discover, there were many “facts” in the manuscript that were contrary to the evidence. Confronting McMahon with the truth would be one of the perils of his engagement.

Mullins introduces the story of the manuscript early in this fine biography. (The phrase in the title, “Tiberius with a telephone,” was Labor leader Gough Whitlam’s description of McMahon’s search for allies to help rid him of John Gorton as defence minister.) Mullins then uses Bowman’s travails as a counterpoint to the McMahon history. Very short chapters about Bowman’s problems with the autobiography are interspersed with long chapters about McMahon’s life and career.

Generally, the accounts of Bowman’s difficulties with McMahon’s credibility allow Mullins to avoid expressing his own views about his subject. But occasionally he corrects the record. McMahon frequently claimed, for example, that he graduated with distinction or honours from a four-year course in economics, which he said he had completed in two years. “The claim was false,” Mullins writes. “McMahon had started the degree in 1944; had claimed credit for courses he had finished in 1928; and had used the exemptions afforded to students who had war service. It had not taken him two years. He did not receive honours.”

For the most part, Mullins relies on the accounts of McMahon’s contemporaries. An enormous amount of material is available through the National Library’s oral history interviews with politicians, senior public servants, journalists and others, as well as from traditional sources — books, articles, newspaper accounts, cabinet records — which the author has supplemented with interviews and correspondence.

Least valuable are McMahon’s own statements, whether oral or in writing. Just as his departmental officials at foreign affairs would discount any aide-mémoire of a conversation he provided if they had not been present at the time, it is wise to treat all of McMahon’s recollections warily.

McMahon’s ministerial career began in 1951, two years after he entered parliament, when he was appointed navy and air minister. In 1954 he became social services minister, then primary industry minister in 1956. It was in that job that he came into close contact with John McEwen, deputy prime minister and leader of the (then) Country Party. As time went by their relationship was to sour to the point that McEwen would veto McMahon as a candidate for the Liberal leadership when Harold Holt fell victim to the surf at Cheviot Beach. In 1958 McMahon became labour and national service minister; then, after becoming deputy leader following the departure of Menzies, he snared Treasury. It was in this position that he came into direct conflict with McEwen, who tried to elevate his trade department to rival Treasury in influencing cabinet’s decisions on the economy.

As detailed by Mullins, McMahon’s progress through these portfolios was anything but smooth. But he was adroit in his use of journalists to advance his interests and had a reputation as a hard-working minister who would always master his brief. He retained the deputy leadership, and the Treasury, when Gorton succeeded Holt. But after he (and several others) unsuccessfully challenged Gorton following the 1969 election, he was moved to external affairs (which he had renamed as foreign affairs).

McMahon finally became prime minister after Gorton’s leadership imploded following a dispute with defence minister Malcolm Fraser. His only rival in the leadership ballot was the young, inexperienced Billy Snedden. It was no real contest.

Having achieved his ultimate political ambition, what then for McMahon? He had just under two years to demonstrate why the Coalition government should have its twenty-three-year reign extended for another three years, to show it was united and had the policies required to advance the national interest, and to prove that he, rather than Gough Whitlam, was the best man to be prime minister.

The battler: McMahon speaking at an election rally at Box Hill, Victoria, in 1972. National Archives of Australia, A6180, 5/12/72/10

Unlike Whitlam, McMahon had no agenda. He turned to the party machine to establish committees to make policy recommendations. These tended to reflect the opposition’s policies in such areas as Aboriginal affairs, urban and regional development, and education, but were less radical and less convincing.

McMahon battled away, hampered, he thought, by problems with his ministers and even his own department, but he was unable to match Labor’s “It’s Time” message and Whitlam’s personal dominance. It all ended badly, and Whitlam became prime minister in December 1972.

It is remarkable that McMahon survived and thrived for as long as he did. Menzies could have put an end to his career in 1959, when McMahon admitted, in writing, to leaking from cabinet. “This is an outrage. I will consider the position,” Menzies noted. But he did not act. And McMahon was not cured. He was forever leaking and lying to advance his own interests, yet he survived and personally prospered, to the regret of most of his colleagues.

Completing a biography of this scope is an enormous undertaking, and Patrick Mullins does it with considerable skill. In the long chapters dealing with the five crucial years of McMahon’s career, from when McEwen blocked his contesting of the leadership in January 1968 to when Whitlam defeated him at the polls at the end of 1972, Mullins conveys the turmoil, the atmosphere of crisis, the bickering and the bloodletting that marked this extraordinary period of Australian political history.

And those lies. I was in the press gallery throughout this time, and at its end Laurie Oakes and I wrote an account of Whitlam’s rise called The Making of an Australian Prime Minister. Afterwards I was challenged by Liberal frontbencher Nigel Bowen (later the first chief judge of the Federal Court) about an error we’d made concerning his role in the planning for the election. “You should have known better,” he admonished me, “than to believe anything the silly little bugger told you.” •