IN THE SUMMER of 2006 I travelled to Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. It was a time of great change and much optimism. A coalition of sharia courts known as the Islamic Courts Union had defeated the warlords, who had ruled Mogadishu and most of the rest of south and central Somalia since 1991. The Islamists enjoyed the popular support of the city’s war-weary population, who could move around freely for the first time in years without fear of robbery or having to pass through warlord-run checkpoints.

The Islamic Courts Union had two main leaders: Sheikh Sharif Ahmed, forty-four, a former geography teacher, and Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, a seventy-four year old henna-bearded cleric who appears on US terrorism lists for his alleged links to al Qaeda. One afternoon my fixer arranged an interview with Ahmed. We met in a heavily shaded room in a house near the mayor’s office.

“We just want to bring peace to the country,” he told me, speaking softly in Somali and trying to stress that being an Islamist did not necessarily mean being a threat to the outside world. “We will not impose anything on the people if the people are against it, not even sharia law.”

There was little time to impose anything. Within months the Courts had been swept out of power by Ethiopian forces backed by the United States, which viewed the Islamists as a terror threat. The weak and corrupt Transitional Federal Government, disliked by most Somalis and completely dependent on Ethiopian muscle, was installed in Mogadishu. Ahmed and Aweys both fled the country, leaving behind a brewing insurgency that claimed more than 16,000 civilian lives in two years, according to local human rights groups.

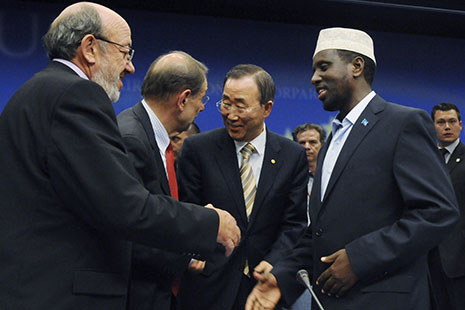

Today the Ethiopia occupation is over and the two former leaders are back in Mogadishu – and on opposite sides. In a twist that would have seemed highly improbable in 2006, Ahmed is now the Western-backed president of the transitional government. He has installed sharia law, though less out of popular demand than as a means of appeasing the hardline Islamist groups fiercely trying to oust his administration. This opposition, which is not united, includes the radical Shabaab guerillas, who have been punishing alleged criminals in areas under their control using amputations, and a more politically motivated militia called Hizbul Islam, which owes loyalty to Aweys.

Aweys returned to Mogadishu in April from Eritrea, where he had set up an opposition group that had strongly opposed Ahmed’s move in government. There were hopes that he would enter in discussions with Ahmed, who had said he was willing to talk to his former ally. Indeed, according to diplomatic sources, Sudan had hosted Aweys for three weeks before his return, with the Sudanese president Omar el Bashir personally trying to convince him to support the transitional government.

Instead, Aweys’s passage home has breathed life into the insurgency, which had slowed significantly following the departure of the Ethiopian troops in January. A day after arriving back Aweys demanded the withdrawal of the 4300 African Union peacekeepers before he would enter into talks, and then called for all Islamist groups to fight the government, which he described as a tool of the West.

Soon Mogadishu was in turmoil once more. Nearly 200 people have been killed in the fighting between pro-government and Islamist-led militias over the past two weeks, and more than 40,000 people have fled the city. Some have headed into neighbouring Kenya, to the world’s largest refugee settlement, Dabaab, designed for 90,000 people, which squats in desert-like terrain. When I visited last August there were 210,000 people in the camp, and no space for new arrivals. Now the population is 270,000, with 5000 more people arriving every month.

The Shabaab, which has capitalised on Somalia’s complex social dynamics by securing the support of some smaller clans that feel marginalised, has gained ground in Mogadishu in the latest fighting and took control of the strategic town of Jowhar, fifty-six miles north of Mogadishu, last Sunday. Hizbul Islam has also made gains. There are reports of several hundred foreign guerrillas fighting alongside the opposition groups, and warnings that the government may soon fall, leaving al Qaeda-linked radicals in charge. Both the likelihood of the government’s collapse and the strength of the Islamists’ terror links may well be exaggerated, but nonetheless there is serious concern as to what comes next.

One of the diplomats who was closely involved in the talks in Djibouti that led to Ahmed joining the government said that both Somalis and international community had “taken their foot off the accelerator” over the past few months, thinking that the worst fighting was over. “There is a very serious risk of underestimating and failing to understand the dangers ahead, particularly among the international community. In New York [at the United Nations], some diplomats are still saying: ‘So Aweys is back in Somalia, and that’s a good thing isn’t it?’ – they still don’t get the dynamics at play.”

While Ahmed appears to have a decent amount of support on the ground, he is under pressure to deliver as president. Admittedly, it is still early days, but his government has so far accomplished very little. It has ministers but no ministries, and the integration of the various pro-government militias into a joint force has barely begun. The latest fighting has pushed him to accept the help of warlords in resisting the Islamist rebels, a move unlikely to win him support from the population.

He may not have had a choice, however. International donors pledged $213 million in defence support to his government last month: two thirds of it to strengthen the African Union peacekeeping mission, and a third to build up the government’s own forces. But the money has not been released due to concerns about accountability.

“It’s madness – think about how much money has been given out in Iraq and Afghanistan, yet governments are still not prepared to give when it comes to Somalia, even when there is a genuine small window of opportunity,” the diplomat said.

Michael Weinstein, a professor of political science at Purdue University in the United States, and an expert on Somalia, said he now expects “a protracted civil conflict” in the country. He believes that none of the main protagonists – which all, including the Shabaab, represent a mixture of “material interests, clan interests and ideological interests” – are strong enough to take overall control. Different groups will control different parts of southern and central Somalia – semi-autonomous Puntland and the breakaway republic of Somaliland have long been areas of relative stability – in a return to the situation that existed prior to the rise of the Islamic Courts Union in 2006, with the cloak of Islam now replacing that of “warlordism.”

“Regionalisation is not the worst thing for Somalia right now,” said Weinstein. “Somalis need to be given a breath of air to work things out for themselves, with the international community keeping its hands off.” •