The sudden collapse of the Assad regime is one of those “in retrospect it was inevitable but no one saw it coming” moments. Exactly where it leaves Syria is still unclear, so it is also one of those “the future is uncertain, but one thing is for sure, things will never be the same again” moments.

Russia and Iran were Bashar al-Assad’s most vital backers, so we can be reasonably confident that for now both are the big losers. After a decade of substantial investment in Syria, Russia has nothing to show other than Assad himself, now taking up residence in Moscow. It is abandoning its air base in Syria, probably its naval base, and in practice its aspirations to be a major player in Middle Eastern affairs, with only its position in Libya to cling on to.

Iran’s investment goes back even further, and its setback is even greater. This comes at the end of a disastrous year for the defining feature of its foreign policy — its “axis of resistance” drawing on radical Shi’ite groups throughout the region, including in Iraq and Yemen, but with Hamas in Palestine, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Assad in Syria as the key components.

To understand the rise and fall of the axis of resistance we need to go back to political ferment that gave rise to the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

In the summer of 1976, when I was a research associate at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, the Iranian ambassador to Britain came to visit. Parviz Radji was tall, urbane, and spoke impeccable English. He represented an immensely strong, rich and ascendant power, buoyed by the surge in oil prices. But he also represented the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who had succeeded his father in 1941. He was an absolute ruler who occasionally experimented with a bit of democracy. He was close to the West, so criticism was muted, not least because he was recycling his oil wealth through huge purchases of Western military equipment. Iran’s military budget rose from $1.4 billion in 1972 to $9.4 billion by 1977.

These purchases were one of the topics for discussion when Radji visited. A recent staff report from the Senate foreign relations committee had concluded that Iran was turning itself into a regional superpower with these purchases but lacked the technical and industrial capacity, along with the personnel, to absorb the new weaponry. We quizzed the ambassador about whether Iran had spent wisely. Had it gone for a form of conspicuous military consumption that looked more impressive on paper than they would be in battle? The ambassador refused to concede the point, dismissing the criticisms as Western condescension, although he did add “anyway, we are only going to be fighting the Iraqis.”

Just two years later the situation in Iran looked a lot different. The oil price was still high but the Shah’s regime was not. The oil wealth had distorted the economy, aggravating corruption and inequalities. Hundreds of thousands of expatriates, many there to look after the many military programs, had combined with the decadence of the elite to challenge the Islamic character of the society. The Shah’s tentative experiments with democracy and human rights had left the middle classes dissatisfied and strengthened rather than calmed dissent.

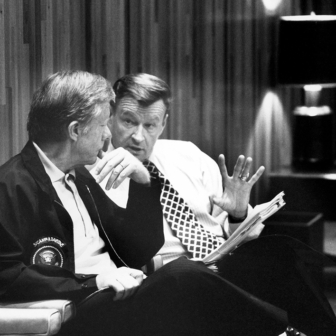

The Shah’s experimentation had begun in 1976 in anticipation of Jimmy Carter becoming US president. Carter was campaigning on a progressive foreign policy opposed to excessive arms sales and promoting human rights. Once in office he was persuaded that the Shah was on the right track and deserved encouragement rather than undue pressure.

At the end of 1977, Carter and his wife attended a banquet in Tehran. Unaware of the discontent gripping Iran, which would overwhelm the regime over the coming year, the president observed to his delighted host: “Iran, because of the great leadership of the Shah, is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world. This is a great tribute to you, Your Majesty, and to your leadership and to the respect and admiration and love which your people give to you…”

(One is reminded in terms of timing of US national security adviser Jake Sullivan’s statement of late September 2023: “The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades.”)

Instead of stability, 1978 was marked by demonstrations, strikes in the oilfield and occasional acts of violent repression. The Shah’s progressing cancer left him uncertain and indecisive about whether and how to deploy the army to crush the gathering insurrection or to try a more liberal and conciliatory approach. As he oscillated between the two, neither had a chance to succeed.

When the Shah eventually fled Tehran in January 1979 I thought back to the earlier conversation with the ambassador (who stayed in London, never to return to Iran). The regime had appeared so powerful, yet a lot of the Shah’s power was of the wrong sort: he had great wealth, ubiquitous secret police and a formidable military, with the best kit that money could buy. But at the crudest level it was the wrong sort of power for crowd control and dealing with angry protests, and at the most fundamental level he had the political problem common to all autocracies. They can never be sure of the state of public opinion and the forces arraigned against them, and the only constitutional changes they can imagine still leave them exactly where they were before, completely in charge.

Some reformers might be prepared to govern more liberally and competently, but in the Shah’s case his most bitter foes could never regard him as legitimate. The 1953 overthrow of Iran’s popular, nationalist prime minister in a US–UK operation (about which they unwisely boasted) meant that he was seen as a foreign imposition. The modernising, secular aspects of his rule appalled the Islamic clergy; the inequalities were exploited by the communist Tudeh party.

The Ayatollah Khomeini provided the public face of the revolution. A long opponent of the regime, he had moved to exile in Iraq, from where he delivered fiery sermons offering an uncompromising Islamism with a leftist slant. These were circulated in cassette form in Iran’s Mosques.

After the Shah lobbied the Iraqi government to expel him, Khomeini moved to Paris which gave him access to the world’s media. Khomeini was widely assumed to be a figurehead and so was consistently underestimated. He knew exactly what he wanted. After the revolution, religious leaders under his direction took control of the country’s supreme levers of power. The other, more secular, elements of the coalition that overthrew the Shah, from the moderate reformers to the communists, were purged and marginalised.

The big crisis came in October 1979 when Carter agreed to allow the Shah to go to the United States for medical treatment. This led to huge pro-revolution and anti-American demonstrations in Tehran. On 4 November some 300 militants occupied the US embassy compound, taking hostage sixty-six diplomats and marines. Attempts by the foreign minister to defuse the situation quickly were thwarted by Khomeini.

The crisis defined the final year of Carter’s presidency and help bring Ronald Reagan to victory in November 1980. The hostages were not released until the day of his inauguration.

Since then there have been periods when possibilities opened up for a rapprochement, but US–Iranian relations have never fully recovered. Even less so have Israel–Iranian relations. Before the revolution, Israel’s second-largest embassy after Washington was in Tehran. The new regime handed the embassy over to the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the new regime made anti-Zionism a centrepiece of its foreign policy.

The year of the revolution — 1979 — was full of incident and turbulence, including the Israel–Egyptian peace treaty, the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, and Saddam Hussein’s becoming president of Iraq. Each of these events helped shaped Iran’s course: the Israel–Egyptian treaty left a gap for new anti-Zionist leadership; the Soviet intervention against Jihadists in Afghanistan was condemned by Khomeini, depriving Moscow of the chance to replace the US as Iran’s superpower friend; the next year Saddam saw an opportunity to avenge the past humiliations wrought by an Iran now in post-revolutionary disarray, and so launched the invasion that began an eight-year war.

The war with Iraq helped the regime consolidate its power. Other wars then helped it expand its influence. Hezbollah, a radical Shi’ite group formed to fight back against Israel’s ill-fated invasion of Lebanon in 1982, was a natural ally. So was the Syrian regime because of its shared antipathy to Saddam’s Iraq and of its roots in the minority Shi’ite Alawites. When the American-led coalition overthrew Saddam in 2003 radical Shi’ite groups, backed by Iran, were soon harassing coalition forces. The Arab Spring of 2011 and the subsequent upheavals saw Iran back the anti-Saudi Houthis in Yemen and then move sharply, with Hezbollah, to keep Assad in power as the deadly civil war began. Here, however, it required Russian intervention, beginning in 2015, to defeat the rebels.

Because its roots lie in the Sunni Moslem Brotherhood, Hamas’s membership of this axis was less obvious. Its leadership couldn’t operate in Palestine and so had been based in Damascus until 2012, when Assad would not accept it taking a neutral position in the developing civil war. The Syrian president saw them as too sympathetic to the local Sunni groups with their own roots in the Moslem Brotherhood. Hamas leaders went instead to Qatar, where they worked to improve relations with the Gulf states.

Even before he became leader of Hamas in Gaza in 2017, Yahya Sinwar disagreed with this path. He cultivated ties with Iran as the best source of weapons with which to threaten Israel and promote the armed struggle.

The idea of an axis of resistance had some basic problems. It resembled the old Soviet Comintern, which coordinated communist parties around the world ostensibly so that they could promote class struggle better in their own countries but in practice to serve as instruments of Soviet foreign policy. In the same way, Iran’s “axis” was there to serve the security interests of Iran, even while offering in-principle backing to the individual members in their own national struggles.

Anti-Zionism might have been presented as the glue holding this axis together but the overriding priority for the Iranian regime was its own security. With ample supplies of rockets and other weapons, Hamas and Hezbollah demonstrated a real ability to resist the Israeli military, at least on occasion. But they had no obvious means of going beyond resistance, and when Hamas tried in October 2023 the result was disastrous for both the movement and for the Palestinian people on whose behalf they acted.

Sinwar assumed that the Iranians took their slogan of “Death to Israel” as seriously as he did, and that the whole axis would therefore follow when Hamas took the initiative. To a degree it did, at least sufficient to demonstrate solidarity with Hamas, but not sufficient to put Israel into real difficulty. Iran wanted to keep capabilities in reserve, especially Hezbollah’s, for its own security needs. It might have hoped that the international outrage at the sufferings of the Palestinians would result in Israel coming to terms with Hamas, as it had done in the past.

But the ferocity of the original Hamas attack propelled Israel into an even more ferocious response, which kept on coming. Not only was Hamas dealt body blows, and its leadership, including Sinwar, killed off, but Hezbollah suffered the same fate, to the point where it had to agree a ceasefire even while Hamas wanted it to continue the fight. Now Hamas is ready to accept a ceasefire without its core conditions having been met.

And then, as if this was not enough, Assad fell. Just a few weeks earlier he had been at an Arab-Islamic summit in Saudi Arabia among leaders who had earnestly sought his downfall. His rehabilitation was almost complete. But his power had relied on external props, and these were being eroded — Russia because of the war in Ukraine and Iran because of the wars with Israel.

Turkey, always keen to assert itself in the lands of the old Ottoman Empire, saw an opportunity to unleash Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, an Islamist group it had been supporting in Syria’s Idlib province, to make a dash towards the city of Aleppo, the city of some of the most bitter fighting of the civil war. Syrian army defenders were caught by surprise and gave way quickly.

The HTS offensive then moved on to Homs, another symbolic place, which turned out to be the regime’s last stand. The fighting there was tougher, and the Russians were still joining in with air strikes, but defeat left the Syrian army demoralised and it began to crumble. Russia and Iran concluded that there was no point in committing more resources to a doomed regime. Assad went to the Russian base at Latakia — to oversee operations against the rebels, he claims — but once the base came under drone attack, the commander advised evacuation, again according to Assad’s account, which is how he ended up in Moscow and his regime came to an end, well over fifty years after his father had first seized power.

For now, HTS provides the closest thing to an interim government in Syria, although a variety of militias who played some part in the struggle against Assad are knocking at the door. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has yet to make up its mind as to whether he wants to encourage a relatively stable Syria, in which Turkey should enjoy considerable influence, or whether — entirely for internal Turkish reasons — take the chance to use another proxy force, the Syrian National Army, to undermine the US-backed Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces. Erdoğan still has the capacity to spoil the party he helped to organise.

Israel, meanwhile, has taken the opportunity to prevent a new Syria turning into a serious threat by striking numerous weapons sites, including those linked with chemical weapons, and seizing border territory.

As an offshoot of al Qaeda with a vicious past, HTS has, shall we say, a reputational problem, and it is also under Western sanctions, which make conversations difficult although not impossible. To overcome this handicap it claims to have reformed, and points to its relatively restrained administration of Idlib as evidence. Its leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, has abandoned his nom de guerre and reverted to his original name of Ahmad al-Sharaa. He is currently engaged in a sort of Gerry Adams tribute act as he seeks to demonstrate that he is a born-again moderate.

In this he has made an impressive start. He doesn’t deny his attachment to Islamic law, but promises to respect minorities, including Christians, and not to pick unnecessary fights with Israel. For now the first priority of the neighbouring Arab governments, along with the Europeans and the Americans, is fourfold: to prevent the country being consumed with more fighting; to start on the path of reconstruction and economic recovery (with less of the narcotics that kept the Assad regime funded); to get refugees back home; and to develop a new constitutional arrangement, which hopefully would involve a more inclusive government and even democracy. Given there is no obvious current alternative, if Jolani/Sharaa can find a way to form an inclusive government then more resources and assistance should flow towards Syria.

Given the presence of many armed factions in Syria, the risks of more violence will be present for some time. But while the Iranian revolution of 1979 had a long gestation its active period was relatively brief and the violence, although not trivial, was contained. Syria has been at war since March 2011 in by far the deadliest of modern Middle Eastern wars. By March of this year, after thirteen years, the death toll was put at around 620,000. Wars brutalise but they also exhaust. HTS wants all the militias to dissolve and put their fighters under the control of the new defence ministry. We wait to see how it will cope with those that insist on keeping their weapons and their independence. But the people will want and deserve some respite from violence.

Are revolutions contagious? It is a thought that must be crossing the minds of the Iranian elite. Can Hamas and Hezbollah reconstitute themselves in much more forbidding settings, with Gazans and Lebanese angry with them for involving them in wars they then failed to win, and with military resupply far more difficult than it has been in the past? What do these events means for the militias in Iraq and the Houthis in Yemen?

Since 1979 the Iranian regime became even more repressive and parasitic as the one it had replaced. As Ali Ansari noted two years ago:

The current regime sees the success of the revolution as consequent on the weakness of the Shah and the central lesson they draw is that one must always show “strength” — here interpreted crudely as force — in the face of protests. To do otherwise is to invite ridicule and collapse for in the absence of affection, fear must hold sway.

But he added that weakness can also be manifested in “a stubborn determination not to change one’s ways — on the pretext that this reflects strength.” The regime has repeated the ways of the past “in the belief that brute force will compensate for corrupt governance.” This, Ali warned, might buy the regime some time but not long-term stability. He was then looking at the protest movements in the county — against both strict religious rule and economic mismanagement.

Now a directly elected and reformist president, Masoud Pezeshkian, offers one route to a more legitimate government. But what he can achieve remains circumscribed by the Supreme Leader, currently the Ayatollah Khamenei. He has been in power since 1989, but his health is poor, and the regime over which he presides is vulnerable. The question of succession looms large, and behind that question is one about the future direction of the regime. Does it continue on its current path of defiance or does it look to rebuild relations with the West if only to ease its economic predicament?

Over the coming months the regime must decide on two issues, both of which could trigger mass protests. The first, and the hardest to avoid, concerns petrol prices. Sanctions and regime dysfunctions have left the oil industry starved of investment and electricity production so low that there are regular blackouts and people are being asked to survive the winter at lower temperatures. The currency has lost almost half its value this year, which means that they can no longer afford to subsidise petrol prices. But the last time they were raised there were intensive and violent protests throughout the country.

The second issue concerns the determination of the hardline Islamists, who currently dominate the parliament, to prescribe appropriate dress for all women. A bill has passed to this effect, a response to the popular protests following the detention of a woman for not wearing a suitable hijab. President Pezeshkian is holding back on implementing the law on the grounds that he has enough problems with a failing energy sector and a failing foreign policy. But the more it appears that the regime is reluctant to crack down on dissent the bolder the dissenters may become.

One argument is that the setbacks of the past year will leave Iran even more determined to complete its nuclear weapons program. Yet Donald Trump has threatened “maximum pressure” if Iran moves in that direction, and for now the regime needs less rather than more than pressure. Also Israel, having taken out Iranian air defences earlier in the year, might welcome a chance to have a go at Iran’s nuclear capabilities.

A belligerent rhetoric that outreached its capacity has left Iran at a crossroads. In 2011 Bashar Assad had an opportunity to reconstruct his regime by accepting the need for more democracy and openness. Instead he chose more repression and fighting, leading to immense death and destruction, and still his regime collapsed in the end. He relied on the wrong sort of power — brute force with little underlying legitimacy. Whether Iran can or should stick to its current course will be hotly debated in Tehran. It can trade military capabilities with Russia, but Moscow is struggling to cope with its own problems and has no spare capacity to help, especially in the economic sphere.

With Iran, as with Syria, as its leaders try to find a new way forward the West shouldn’t watch passively, reflecting on the unpredictability of events, waiting to see what turns up. This is an opportunity for significant engagement.

Less than a month ago, following the Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire, I asked, without quite answering, the question of whether Trump could do a deal with Iran. The sudden fall of Assad provides the new administration with even more of an opportunity. I concluded that piece with the observation that: “The optimists can point to the positive benefits of a grand project of peace-making; the pessimists can point to the likely pitfalls along the way.”

Much depends, of course, on the extent to which Trump’s team sees the possibilities opening up in the region, and on its ability to work with Europeans and Arab governments, as well as Israel, to take advantage. Will it even be bothered to try? This remains a region where chaos seems always around the corner. But for once, as ceasefire agreements are signed, and a brutal dictatorship falls, we can at least allow ourselves a moment of optimism. •