The Year Everything Changed: 2001

By Phillipa McGuinness | Vintage | $34.99 | 320 pages

“Study problems, not periods,” advised Lord Acton, the first modern historian. History became modern when it became critical, forsaking mere chronicle for investigation and explanation. At least that’s what we thought back in the 1960s and 70s when the grand narratives of Hegel, Marx and Weber inspired hopes that the study of history might reveal the hidden springs of social change.

Such hopes now seem a distant memory. Some of today’s most popular histories don’t study problems, or even periods: they narrow their gaze to a single year. In 2012 Good Reads compiled a list of 130 “Books with a Year for a Title.” Here’s a sample: 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed; 1492: The Year the World Began; 1942: The Year That Tried Men’s Souls; 1968: The Year that Rocked the World; 1421: The Year China Discovered America; 1919: The Year Our World Began. The genre flourishes especially among American authors and publishers: many of the years that supposedly “changed the world” — 1492, 1776, 1861, 1941 and 1968 — changed the New World more than the Old. But similar titles on the pivotal years of European history — 1066, 1215, 1453, 1688 and 1789 — now abound in bookshops on the other side of the Atlantic. In 2005 the formula arrived in Australia with American-born journalist Gerald Stone’s 1932: A Hell of a Year. Since then we’ve had David Hill’s 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet, James Boyce’s 1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia and now the latest, Phillipa McGuinness’s The Year Everything Changed: 2001.

So, what’s going on here? Is this an intellectual retreat from the complicated history of periods and problems to a kind of mini-history? Or just a fad, a clever way of packaging the past in parcels small enough, and with labels inflated enough, to catch the attention of readers more attuned to memes than tomes. Or was Francis Fukuyama right after all, and history — at least the old kind of history — really did end in 1989?

Well, of course, there are still plenty of history books that study large periods and tackle big problems. Books like McGuinness’s are just one manifestation of a general shaking up of traditional ideas of chronology and causation. Side by side with these little histories — and, yes, there are also histories of months, weeks and days that changed the world — we have seen the flourishing of big history in books like David Christian’s Maps of Time, which survey everything between the Big Bang and yesterday.

Reading The Year Everything Changed, I had a pleasant sense of deja vu. Thirty years ago, I co-edited Australians 1888, one of a series of “slice histories” inspired by the late Ken Inglis as a birthday present to the nation for the Bicentenary. In her day job, as a leading publisher of history books, McGuinness has nursed books by several veterans of that project, including me. In fact, she began to think about her own “slice history” at a conference to celebrate the achievements of another veteran of the bicentennial history, Alan Atkinson. But there are differences, subtle and profound, between our project and hers. The years we wrote about — 1788, 1838, 1888 and 1938 — were also anniversary years, but in “slicing” them we were not interested in what made them momentous as much as what made them ordinary. By focusing on a single year, we could expose the deep structures of everyday Australian life. By ignoring what came afterwards, we noticed things that mattered to contemporaries, even if they didn’t matter to posterity. McGuinness caught something of the spirit of that enterprise when she set out to read at least one newspaper from every day of 2001 in order to “trace a shift so seismic that it has wiped our memories of what things were like before.”

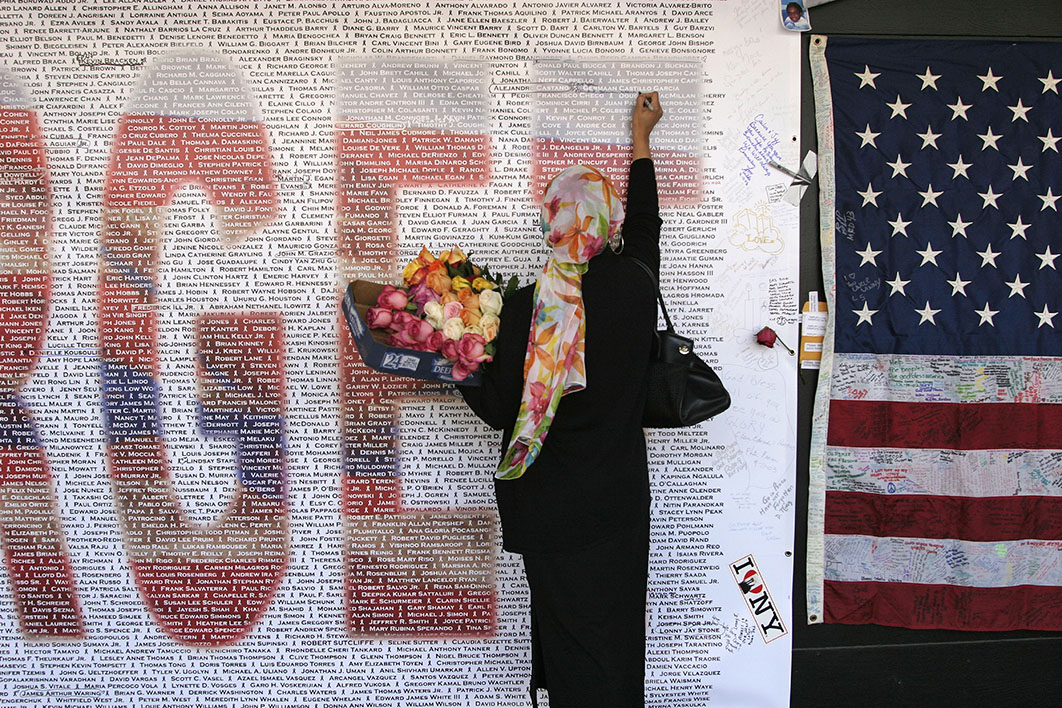

But if The Year Everything Changed is not quite like the bicentennial histories, neither is it quite like those popular histories of years that “changed the world,” “tried men’s souls” or “ended civilisation.” Unless you are an astrologist, there’s nothing particularly magical about a year. It can’t “change” or “try” or “end” anything of itself, and even if it could, we couldn’t know that it did without looking beyond the year itself. Yet there are unquestionably times when events seem to speed up, either in the world at large or in our own lives, or sometimes uncannily in both together. Then, like dominoes, or atoms in a chain reaction, events act and react upon each other to disrupt our equilibrium and reorder our sense of reality. Two thousand and one was such a year. This book is an invitation to relive it: to recall where we were when we watched the plane hit the towers (“we knew we were watching history”), to feel again the shock, anger and fear, and to measure their effects in the cooler light of hindsight.

There is more than one way to write the history of a year. Elisabeth Asbrink’s admired 1947: When Now Begins follows a small cast of notables — Christian Dior, Simone de Beauvoir, Harry S. Truman, Lord Mountbatten, George Orwell — through the months of the year, pausing midway to recount her own Hungarian-Jewish grandfather’s story (“Days and Death”) in the aftermath of war and deportation. McGuinness adopts a less intricate structure: a chapter for each month, and a theme, usually highlighted by an emblematic event, for each chapter. In January the centenary of Australian Federation, an “inconsequential” celebration of an uninspiring, but consequential, national birthday, prompts her reflections on the place of history in national life, a theme continued in February, when the death of Don Bradman leads to consideration of other heroes and celebrities. In March, recollections of the almost forgotten days of dial-up internet, when Encarta dominated Wikipedia and Google had yet to make a profit, inspire the author-publisher’s reflections on how technology has so rapidly changed the ways in which knowledge is made and disseminated.

McGuinness’s soft-left sympathies (“wearing my heart on my sleeve as usual”) come to the fore in April, May and June in chapters on human rights, religion, the economy and population. She invites us to ponder what we knew and didn’t know, what we expected and simply did not foresee, in 2001. How much of the story of clerical abuse, revealed by the 2017 royal commission, was already visible, but unattended to, in 2001? Why did the rights of same-sex couples to marry, a cause then hardly on the horizon, advance so quickly while those of asylum seekers in offshore detention, so well publicised in 2001, remain unrelieved a decade and half later?

From August, the story grows in pace and intensity as McGuinness relives the concatenating crises of Tampa, 9/11, Bush’s declaration of the war on terror and the Australian election in November. “So much happens,” she remarks, “that were it a novel the author would be criticised for over-plotting.” Into a clear, well-paced narrative she inserts her own questions and reflections, sometimes asking participants, including Kim Beazley and John Howard, to offer their own reconsiderations. Howard is a key witness, for his presence in Washington and bonding with Bush in the aftermath of 9/11 catalysed his government’s commitment to the war on terror and to the congealing of fear and xenophobia that culminated in the November election. Drawing on the recollections of close colleagues, McGuinness’s account of Howard’s cool conduct in Washington is almost admiring. If she hoped, however, that hindsight had caused him to revise his view of events, she is disappointed, for if he has, he certainly wasn’t telling her. And maybe that’s the point: the steely self-belief that enables a Howard to act so coolly in a crisis is also what makes him impervious to the self-questioning that is second nature to historians.

The Year Everything Changed is an ambiguous title, deliberately so, for the book is not just about how “everything” suddenly changed in the wider world after 9/11, but how everything changed for the author herself. Through much of the year she was living with her partner in Singapore, viewing Australian events with the combination of passion and powerlessness that sometimes afflicts the expatriate. In December, an already dark year turned yet darker with the stillbirth of the couple’s son Daniel. For years, the story of Daniel was unknown even to many of Phillipa’s friends and associates. In telling it, she is acknowledging how the personal and the public became fused in her recollections of that year. “Sadness about everyone else’s loss flowed in and swirled around with my own grief,” she writes. She was “channelling the pain of the world.”

I understand what she means, for those last months of 2001 were dark ones for my family too. Along with the rest of the world I had watched transfixed as the twin towers collapsed. On the following evening, 9/12, we joined my sister Jan for dinner in a Collingwood pub. It was her fifty-fifth birthday. After years of struggle, life had at last been looking up for her. She had returned to study, completed an accounting degree and risen to the top of the Victorian auditor-general’s office. But in late August she had been diagnosed with advanced inoperable breast cancer. The doctors thought she might still have a year or two, but our celebratory dinner was overshadowed by the fear it could be the last. Our dread suddenly turned apocalyptic with a telephone call from her daughter, then holidaying in the United States. On the morning of 9/11, two days after she visited the World Trade Center, she had been standing outside the White House when the plane hit the Pentagon. A sudden chill enveloped us. A few weeks later Jan’s condition worsened and by the end of October she was gone. There is no intelligible connection between that personal agony and the convulsions of the world at large, but even today I cannot think of 9/11 except through its dark prism.

In Lord Acton’s view, the “calm and scientific spirit” of the critical historian requires us to put aside such personal experiences and allegiances. In the 1960s E.H. Carr took Acton to task in a famous critique of historical objectivity, What Is History? And ever since, historians have been steadily widening the scope for the expression of personal experience and opinion. History is the richer and more engaging for it. But can they widen it too far? When does personal experience illuminate the past, and when does it distort it? Acton’s advice may be a counsel of perfection, but doesn’t subjectivity also have its limits?

McGuinness shares these worries. “Am I trapped in a simplistic narrative of my own making?” she asks. Conscious of her own biases, she responds by drawing up a balance sheet of the year, seeking secular surrogates for the departed vestiges of religious faith. In a bleak year, she reminds herself, there are still things — “penicillin, defibrillators, pinot noir, the vote, the golden age of television” — to be thankful for. And, above all, the love of other humans. “Secularism,” she decides, “did not render faith obsolete.” Yet faith and hope, surely, are not the dividend of a historical calculus for, as she also notes, they may flourish most when times are especially bad.

Readers seeking definitive accounts of 9/11, Tampa and the November election campaign are still likely to turn to other books, such as the brilliant 9/11 Commission report or, closer to home, David Marr and Marian Wilkinson’s Dark Victory and Paul Kelly’s The March of Patriots, works that appear prominently in McGuinness’s footnotes. The Year Everything Changed may not advance our knowledge of why each of these events unfolded as it did, nor of the political debates they unleashed. What it offers is something different: an understanding of how history is seen and felt, from the vantage point of a candid, historically literate, morally engaged witness to an extraordinary time. In reliving the year with her, we better understand how events, often considered distantly and separately, concatenated in time and reverberated in the minds of contemporaries to generate a palpable sense that “everything” had changed. Since there is no sign that everything will stop changing, we may need such perceptive, humane histories more rather than less in the uncertain years ahead. •