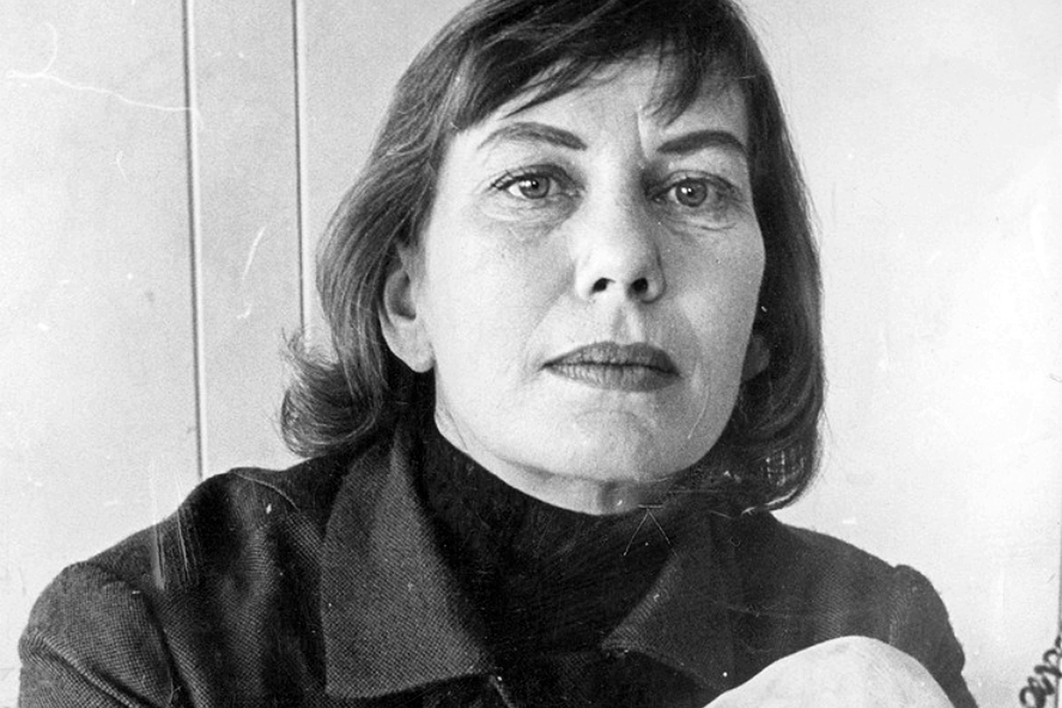

“There is a sort of dreamlike quality in returning to a place where one was young. Memory is as tricky as a flawed window glass that distorts the view beyond according to the way one turns one’s head.” So wrote Charmian Clift in 1964, months after returning from the Greek island of Hydra to Australia, in the first of the newspaper columns for which she is best remembered.

Clift and her husband, journalist and writer George Johnston, were broke. His novel My Brother Jack had been published but was yet to earn. She was writing out of economic necessity.

Her work appeared on the women’s pages of the Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Herald, surrounded by advertisements for cosmetics and margarine. She had just 500 words. Yet over the next five years she was to push the form of the women’s column to its limits, writing 240 mini-essays that used a confident, personal and above all conversational tone to reflect on Australian society.

By the time her contract to write the column was confirmed the following year, she had criticised consumerism, accused Australians of being conformist, ridiculed advertising and attacked the Australian government’s commitment to the Vietnam war, which both newspapers supported. But such was her following that the Sydney Morning Herald’s main advertiser, Grace Brothers, insisted that its advertisements should be placed next to her column. She had been given a permanent prime position on page two of the women’s section, and the paper’s mailroom was deluged with fan mail.

The early columns were bounded by domesticity, but as the decade developed they became explicitly critical. Clift wanted a brave Australian national identity, “a real cultural and social flowering, spiky and wild and refreshing and strange and unquestionably rooted in native soil.” When demonstrations disrupted the ceremonial motorcade of visiting US president Lyndon Johnson in 1966, she wrote about the right of dissent, “something that we Australian people used to hold dear, all the way back to the Eureka Stockade.”

She raged against complacency. Australia was “so bland and even meek in the character of its people… [F]ar from being anti-authoritarian as I always believed, they actually seem to derive a sense of comfort and ease from unquestioning submission.” On her list of things that had been too easily accepted were conscription to the Vietnam war, the “tragic” departure of the Sydney Opera House’s architect, Jørn Utzon, and Australia’s treatment of Aborigines.

Born and brought up in the NSW coastal town of Kiama, Clift’s first job in journalism was writing for and editing an army magazine, For Your Information, when she was a lieutenant in the women’s service during the second world war. She was twenty-one years old.

In civilian life, the army’s head of public relations, Brigadier Errol Knox, was the managing director of the Melbourne Argus newspaper. Impressed by Clift, he hired her to work on the paper as soon as she was demobilised in 1946.

It was at the Argus that she fell in love with George Johnston, a famous war correspondent who was then editing a new weekly magazine, the Australasian Post. Johnston was eleven years her senior and married with a child. Their very public affair was the talk of the town, cutting short her career at the paper. She was sacked by management, and Johnston resigned in protest.

In 1954, they committed to a literary life and moved to Greece, first to the island of Kalymnos and then to Hydra. It was here that Clift began to publish books in her own right, with two autobiographical books of travel writing, Mermaid Singing (1956) and Peel Me a Lotus (1959).

On Hydra, Clift and Johnston were at the centre of a community of artists and writers that has been almost mythologised in retrospect. They were visited by the then-unknown author and poet Leonard Cohen, who gave his first performance as a singer. “The Australians drank more than other people, they wrote more, they got sick more, they got well more, they cursed more, they blessed more, and they helped a great deal more,” Cohen later wrote. “They were an inspiration.”

Other visitors to Hydra included journalist Mungo MacCallum, artist Sidney Nolan, actor Peter Finch and writer Rodney Hall. It was a hard-working, hard-drinking, bohemian community of unusual freedom. Clift’s first solo novel, Walk to the Paradise Gardens (1960), was followed by Honours Mimic (1964). All four of her books were well received in the United States and Britain, but barely distributed in Australia.

The couple returned home when George Johnston’s most famous book, My Brother Jack, was published. Clift found she was not allowed to enter public bars in Sydney, and everywhere women were constrained. How much longer was it going to be, she asked, before “society faces up to the fact that women are fully fledged members of the human fraternity and as such entitled to participate in its economic, social and cultural life on terms of absolute equality?”

Clift had developed a serious drinking problem on Hydra that continued to plague her for the rest of her life. She also found her sudden public profile difficult, saying to a friend, “There is this woman, Charmian Clift. And I have to dress up as her and go out and be her.”

On 8 July 1969, just before George’s latest novel, Clean Straw for Nothing, was published, Clift took a fatal dose of sleeping tablets while drunk. The artist Joy Hester, a close friend, said that Clift’s depression at the time was partly the result of the book’s fictional depiction of her extramarital affairs during the Hydra years. Johnston died a year after the book was released. •