President Trump was bad for Australia. We rely on trade, foreign capital and immigrants for our economic prosperity. We rely on international institutions for our influence and security. We rely on the World Trade Organization for trade rules, the Paris Agreement for action on climate change and the World Health Organization for tackling global health crises, particularly in developing countries. Australia is not a superpower. Strong, predictable international rules and norms are vital to our interests.

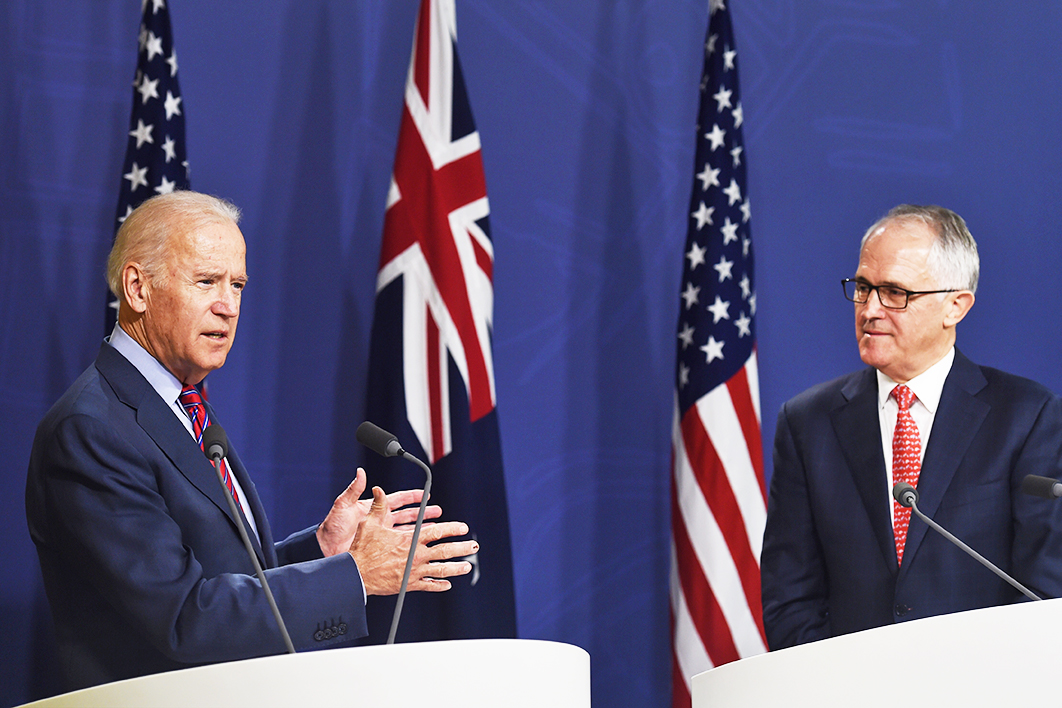

One by one, Trump attacked these things. He attacked Australia indirectly by undermining the things we rely on for our prosperity and security. He attacked Australia directly by threatening our exports and threatening to rip up bilateral deals agreed with the Obama administration. Uncertainty around the longstanding Australia–US alliance saw prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison scramble to keep Washington happy, often forced to choose between the alliance and Australia’s broader economic and security interests.

Many in Canberra breathed a sigh of relief when Joe Biden finally secured the 270 electoral college votes needed to become the forty-sixth president of the United States. But they shouldn’t celebrate too quickly. They should remember that, on the current numbers, almost 48 per cent of US voters backed Trump. President Biden will give the world a much-needed reprieve from Trump’s chaotic foreign policy. But he will only buy us time. The structural forces that produced Trump — most notably America’s rising inequality — haven’t gone away, and the Democrats’ failure to win the Senate means Biden will struggle to do much to deal with them. Given Trump 2.0 may be just a few years away, the question needs to be asked: is Australia too dependent on America?

President Trump was always quick to blame the rest of the world for America’s woes. Covid deaths? Blame China. Lost jobs? Blame trade. Declining wages? Blame immigrants. Declining manufacturing? Blame Germany. Declining coal industry? Blame Paris.

It was good politics. A president has little influence over domestic policy, particularly when the president’s party doesn’t have both the House and the Senate. Framing domestic problems as having global causes gave Trump policy levers to pull and the appearance of being in control. But this only worked for so long. Reality eventually caught up with him: these challenges weren’t international, they were domestic.

The evidence is clear. Countries with strong social safety nets haven’t seen the disastrous outcomes experienced in America’s rust belt. Countries with strong social safety nets have been better at spreading the benefits of trade, better at managing the downsides of trade and better at managing the transitions that come from automation and technological change. Countries with strong unions, strong productivity growth, strong competition between firms and generous social welfare payments haven’t seen the declines in wages and household incomes on the scale America has. Countries that don’t borrow hundreds of billions of dollars from overseas each year to finance government, household and business debt don’t have the big trade deficits that America has. And while Covid-19 came from overseas, almost every country in the world has used domestic policies more effectively to manage the pandemic better than America has.

So it’s little surprise that, after four years of Trump’s misdirected blame game, none of these challenges has gone away. In fact, most have got worse. It’s evidence of a failed Trump presidency. But it’s also evidence of the massive challenge facing president-elect Biden. While the race to the White House determined whether Biden would become president, the race in the Senate determined how successful his presidency would be.

There’s only so much Biden can do with regulations and executive orders. Addressing rising inequality and disadvantage in America will require deep reforms of tax and welfare systems, healthcare, labour markets and product markets, and an expanded social safety net. This is a tall order after an election in which the main line of attack was that Biden and his associates are rampant, frightening socialists.

A Trump re-election would have confirmed what America’s structural challenges already revealed: that Trump was no accident. His re-election would have sparked a global rethink of foreign policy towards America. A narrow victory for Biden is no different.

This raises difficult questions for Australia. The US alliance is the cornerstone of Australia’s foreign policy. It underpins our defence strategy. It’s more vital than ever in a world with a more assertive China, an aggressive Russia and an unstable Middle East. But the more the United States attacks the rules, norms and institutions that underpin Australia’s prosperity and security, the more strained that alliance will become. As America’s behaviour becomes more extreme, and as the cost–benefit ratio of the alliance shifts, Australia will need alternatives.

For many, the answer is a strengthened military, and even developing an Australian nuclear arsenal. But that conversation typically ends once we acknowledge the sheer scale of the investment needed, the toxic domestic politics that it would provoke, the threat of prompting a regional or even global arms race, our obligations under international law, and a host of other considerations that could actually make Australia less secure.

A better option is to build coalitions in the region, make war more expensive and strengthen multilateral institutions. Numerous countries in Asia are in the same position as Australia in trying to balance an assertive China and an unreliable America. Substantially deepening economic and military cooperation with those countries will build a powerful coalition that leverages Australia’s position.

Strengthening trade and financial links throughout the region, and bringing China and the United States into those agreements as much as possible, will make war more expensive and diplomacy the more attractive option. Strengthening multilateral institutions by better using the G20 and APEC to coordinate global actions, particularly in response to Covid-19, will help redirect difficult bilateral relationships with superpowers to forums where Australia can work collectively with like-minded countries.

These are all long-term propositions, but Biden’s election buys us the time to get started. Australia had best start preparing now so we are better placed for when Trump 2.0 arrives. •