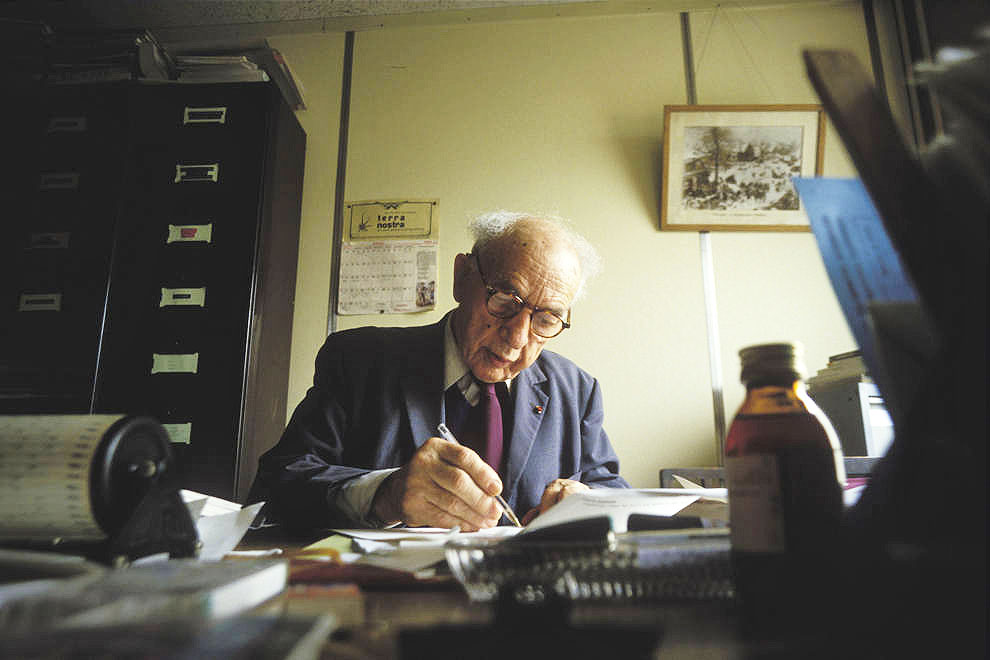

The “problem” of population ageing has been a staple of political pontification for decades. In fact, the main points covered in the average think-piece on the topic were old hat well before many of us were born. The great French demographer Alfred Sauvy discussed most of them in an article entitled “Social and Economic Consequences of the Ageing of Western European Populations” published back in 1948. (His analysis also extended to “countries with a similar civilisation” across the English-speaking world.) Where he was right and, more importantly, where he was wrong, Sauvy presented the key points more clearly than most of his successors.

The Frenchman observed a trend that extended back at least a century. This was the “demographic transition” from a population with high birth rates, high death rates and a low average age to one with low birth rates, low death rates and a high average age. “Ageing happens, as it were, from both ends,” he wrote, “that is to say by a decrease in natality (fewer young people) and by the lengthening of human life (more old people).”

As it turned out, Sauvy was prematurely correct about the decrease in natality. That long-term trend was interrupted by the “baby boom,” which was just beginning when he wrote his essay and was initially believed to be a temporary blip once couples were reunited after the war.

But even in error, Sauvy was closer to the mark than today’s ageing alarmists. In the standard version of the story, baby boomers are seen as the major cause of population ageing, responsible for all manner of social ills. In reality, the baby boom deferred the demographic transition by several decades. If the boom hadn’t occurred, the average age of the population would have risen much earlier.

A more fundamental conceptual error in Sauvy’s framing of the problem, repeated in nearly every subsequent treatment of the topic, is that populations are ageing. This isn’t the case: populations don’t age, people do. In fact, each of us ages at the rate of precisely one year per year, until we die. The longer we avoid death, the older we get and the greater is our contribution to the average age of the population. From this viewpoint, the ageing “problem” is best summed up by a witticism popularised by the actor Maurice Chevalier: “Growing old doesn’t seem quite so bad when you stop to consider the alternative.”

The logical error here is the “fallacy of composition.” The fact that the average age of a population is rising, or falling, says nothing about the individual experience of members of that population. Most obviously, “population ageing” implies a future that is exactly like the one we have at present except that old people are more numerous and young people are fewer. People at any given age, it’s assumed, will have much the same characteristics and live in much the same way as they do at present. This way of thinking is wrong for at least three reasons: because of changes in healthcare, in work and in technology.

First, the assumption that, say, sixty-five-year-olds in the future will be much like sixty-five-year-olds have always been, except more numerous, is inconsistent with the main process leading to population ageing – namely, that people at older ages can now expect more years of continued life. If the average sixty-five-year-old can expect to live twenty years today, he or she must be healthier than the average sixty-five-year-old of the 1950s, who could expect only thirteen years.

The mistaken assumption goes right back to the beginning of the ageing literature. Sauvy, at least, made it explicit:

A progressive unlevelling occurred because of the considerable progress of techniques and the almost total powerlessness of biology upon senility. Though the infant in its cradle finds its expectation of life increased… sclerosis of the crystalline always begins at twenty-five.

He noted that “this statement is made without prejudice to the possible progress of science in the future,” and his example illustrates the point very clearly. “Sclerosis of the crystalline” is an obsolete term for macular degeneration leading to nuclear cataracts of the eye, which are now both preventable and easily treatable.

The same is true of loss of mobility and many of the other disabilities traditionally associated with ageing. Improvements in diet and exercise based on a better understanding of conditions like osteoporosis make it possible to maintain good health for longer. Anti-arthritic drugs mitigate the effects of chronic conditions.

Treatments like hip replacements, now routine, provide years of extra mobility. Alarmists often see such treatments as a huge cost burden. But a hip or knee replacement costing $25,000 is a bargain however you look at it. It’s much less than the cost to society and the patient of six months in a nursing home. More pointedly, it’s less than the cost of a new car, seen as a necessity for working-age people to achieve the mobility needed to go to and from work.

Even dementia, where there has been little if any advance in treatment, is declining in its age-specific prevalence. This is a by-product of improved cardiovascular health and (more speculatively) increased education levels among the middle-aged and old.

These factors, and declines in other sources of premature death – including infant mortality, infectious disease, car crashes and smoking – have helped extend the “standard” lifetime at every stage, with middle age running into the sixties and healthy old age into the seventies and eighties. At the end, there is a period of frailty and decline, leading inevitably to death. The really big costs in the medical system are those incurred in the last year of life. And, by definition, the last year comes only once in a lifetime.

The second and closely related problem is the assumption that patterns of work won’t change. This is illustrated most clearly in the way the Australian Bureau of Statistics divides up the population. For the ABS, the working-age population is made up of people aged fifteen to sixty-four, which reflects the fact that when the definition was formulated it covered the years between the school-leaving age of fifteen and the statutory retirement age of sixty-five. On this basis, the ABS calculates a “dependency ratio,” namely the ratio of those outside the fifteen to sixty-four age range (“dependants”) to those within it.

This definition has remained unchanged even though the school-leaving age has increased to seventeen, compulsory retirement has been abolished, and the pension age is set to increase to sixty-seven (with a further increase to seventy on the cards). In practice, most young people are dependent on their parents into their early twenties and sometimes beyond. Retirement ages are so variable as to defy any precise definition, but it seems clear that after falling for most of the twentieth century, the average age of retirement has started to increase. A truer and more useful comparison would incorporate these changing circumstances.

Finally, and more subtly, discussions of population ageing ignore the technological progress that has been one of the main contributors to reductions in mortality. Technological progress has led to increased productivity and has largely eliminated unskilled jobs in many parts of the economy.

Two implications flow from this. First, young people must spend more time in education to acquire the skills needed for a technologically advanced economy. While dependency ratios are calculated on the assumption that working life begins at fifteen, the reality is that high school completion is the norm, and that a majority of young people acquire post-school qualifications of some kind. The need for education means that the increase in the birth rate sought by former treasurer Peter Costello would take many decades to yield net economic benefits.

The decline in unskilled jobs and the increase in years of education mean that more people are capable of working longer if they choose. In the economy of the twentieth century, access to the age pension at sixty-five was an obvious boon to the typical unskilled worker who might have spent fifty years working in a physically demanding job. This group of workers hasn’t disappeared, but it now represents less than a fifth of the workforce. For the majority, retirement at sixty-five is no longer a physical necessity; rather, it is the outcome of choices, personal in the case of voluntary retirement, or social, in the sadly common case where older workers find themselves unemployed and unable to find new jobs because of age-related bias.

As a society, we have the choice of taking the benefits of improved technology in the form of reduced lifetime hours of work. We could continue, as we did for much of the twentieth century, to lengthen the period of retirement. Alternatively, and more sensibly for many people, we could reduce the intense workload experienced during the peak years of work and family responsibility (roughly age twenty-five to fifty-four) while delaying full retirement until seventy or later.

The increase in longevity produced by improved medical treatments, reductions in the risk of death, and healthier living is a huge boon for Australians, individually and collectively. Yet the framing of the issue around “population ageing” has presented it as a near-catastrophe, not only creating unnecessary negativity but also closing off discussion of the opportunities created by our longer lifespans. We need to stop talking about “population ageing” and start talking about people living longer and healthier lives. •