Paul Schrader’s Oh, Canada begins with the preparation of a room. There’s a practised efficiency as well as a ritual quality to the way three people unpack boxes, move furniture, shift a Christmas tree, set up cameras, monitors and lights, mark a spot on the floor with an x made out of gaffer tape. This is a rare straightforward moment in a film with an apparently simple premise: the recording of the recollections of a dying man.

The people setting up the room intend to make a documentary account of a life. But Oh, Canada itself becomes, in messy, vivid, cinematic detail, something more slippery: a story of mortality, morality, memory and deception. The camera functions as a confessor, but it might or might not capture what the subject intends to reveal or seeks to hide.

Schrader’s fifty-year life in movies, with more than a score of features as a director, is a long, intense accumulation of obsessions and challenges, surprising turns and returns. With Oh, Canada, he revisits crucial elements of two of his significant films. He has cast Richard Gere, the star of American Gigolo (1980) in the central role and he has adapted a book by the late Russell Banks, whose novel Affliction he filmed in 1997.

In Oh, Canada (based on Banks’s Foregone, published in 2021) Gere plays Leonard Fife, a dying documentary filmmaker and teacher who grants an interview to two former students, Oscar-winning husband and wife duo Malcolm and Diana (Michael Imperioli and Victoria Hill). They visit him in hospital to pitch the project, one that will renew interest in his work, making him “as big in the Canadian collective memory as Glenn Gould,” and burnish his reputation as a political filmmaker who left the United States as a draft resister in the 1960s.

Are Malcolm and Diana as well-intentioned as they present themselves? Certainly not; and towards the end of the film they make decisions that are opportunistic, to say the least.

Leonard accepts their offer and agrees to return to his handsome Montreal apartment for a day-long shoot. Frail and cranky, he also has his own agenda for the interview. He intends to engage with his past on his terms; he wants the clarifying gaze of the camera, and he insists that his wife Emma (Uma Thurman) — a former student and later his filmmaking partner — be the person to whom he confesses.

He interrupts Malcolm’s first question with a declaration of his own. “The story begins on March 30, 1968, in Richmond, Virginia… That’s when the poison flower first bloomed.” And he is off on what seems to be a succession of tangents, a feeling heightened by Schrader’s fragmented, calculatedly chaotic approach.

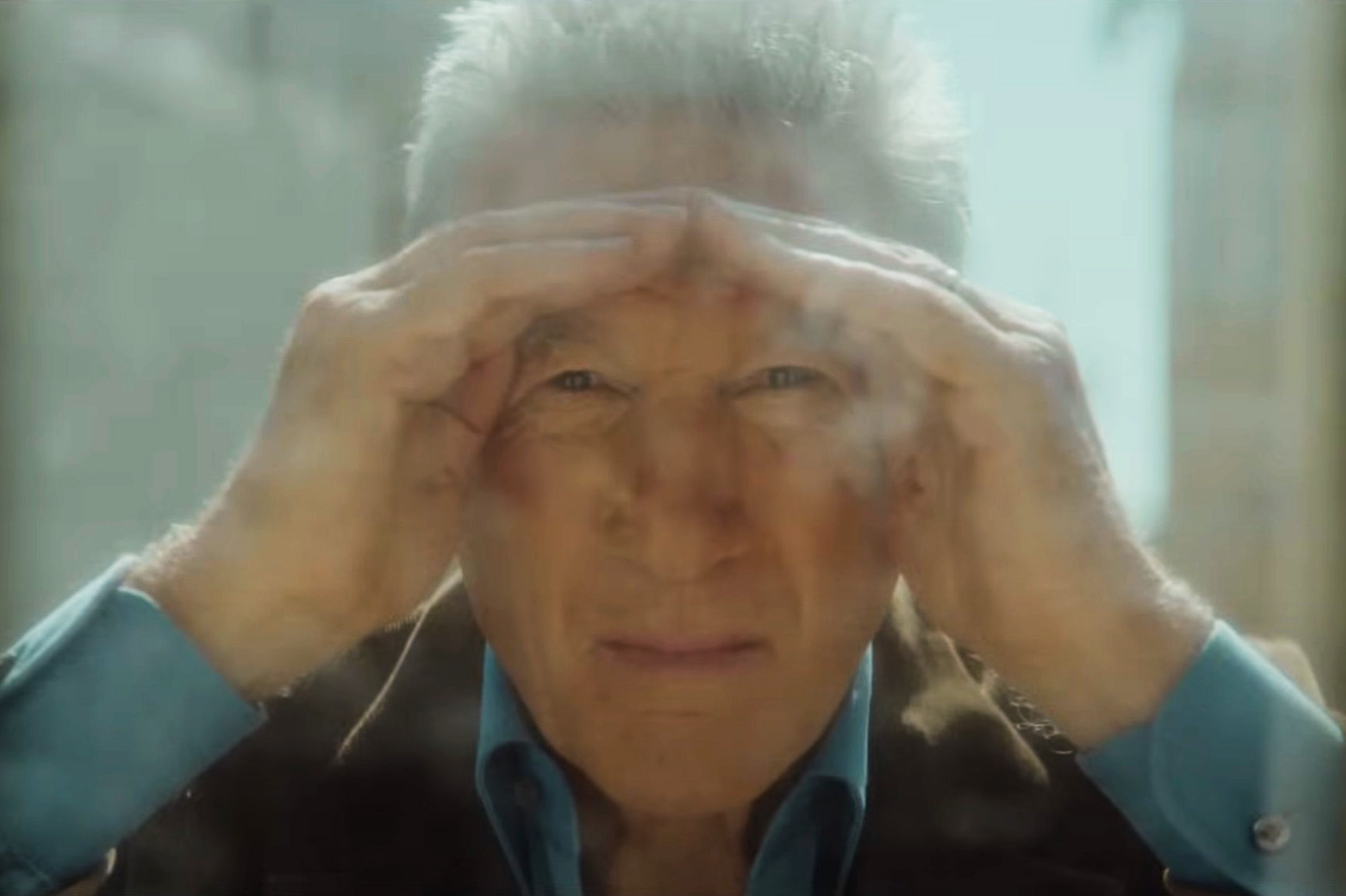

In American Gigolo, Schrader’s camera presented Gere as an object of beauty and launched him as a star. Here, in the unsparing gaze of Malcolm and Diana’s camera, he is fragile and worn-out: close-cropped grey hair, unshaven, mottled skin, impatient and wavering all at once.

Leonard has chosen to begin his story with a decisive moment, when he was an early-career academic in his mid-twenties, married into a wealthy Southern family, with a young son and another child on the way. There was a choice to be made on that day. And there was, it turns out, already a backstory to the backstory.

“When you have no future,” Leonard says, “all you have left is your past. And if your past is a lie…” In exploring what that might mean, Oh, Canada is a patchwork of memories, flashbacks, detours and asides, vividly, variously and sometimes awkwardly represented. Leonard is played in flashbacks to his teens and twenties by Jacob Elordi (Elvis in Priscilla, the rich kid in Saltburn). He and Gere are not an obvious physical match, but Elordi creates a convincing version of Leonard’s voice and his loose physical presence, summoning up a seemingly malleable yet elusive figure, a young man with literary ambitions and an inclination towards secrets and lies.

Schrader’s timeline is not straightforward. He disrupts and elaborates in various ways: changing aspect ratios and colour schemes, introducing an occasional voice-over from Leonard’s adult son, letting characters and incidents drift in and out. The division between Gere and Elordi is not always clearcut; sometimes memory becomes projection and Gere briefly displaces Elordi in scenes from the sixties. A couple of actors play more than one role: once again, it is as if Leonard’s memory is feeding off the presence of people in the room.

Some flashbacks flesh out the story Leonard is telling the camera, others feel more like half-buried recollections that remain unspoken, or may even be fantasy or embellishment. Scenes in black-and-white seem to signify a greater authenticity; it’s not clear whether they are ever revealed to the camera. It is as if they are Leonard’s uncomfortable recollections of what he cannot bear to say aloud.

His final admission, his greatest shame, comes close to the end. It does not feel, however, like a startling discovery or a devastating revelation. It is part of Oh, Canada’s texture of shame, guilt, uncertainty and unreliability, of notions that resonate beyond the specific details of an individual life. •