Vexed: Ethics Beyond Political Tribes

By James Mumford | Bloomsbury Continuum | $31.49 | 224 pages

James Mumford is vexed. He strongly objects to a world in which a person’s identity as a liberal or conservative determines what view he or she takes on every controversial moral issue. He doesn’t see why a person on the left who supports social equality and opposes discrimination must take a pro-choice position on abortion or favour legalisation of drugs and assisted suicide. Nor does he see why conservatives who believe in family values and individual responsibility must support the right to bear arms or back measures that disadvantage people on welfare. He has a problem with what he calls “package deal ethics.”

These package deals, he says, are responsible for the political tribalism that divides families, causes rifts in public institutions, makes compromise and reconciliation impossible, and “cancels” those who dare to dissent from any aspect of their group’s platform. Ethical packaging is a personal problem for Mumford because, as he says, he wants to be a public intellectual who can make a name for himself on social media by expressing controversial views without being blocked or unfriended.

Why should those of us who are not especially concerned about Mumford’s career as a public intellectual share his vexation over ethical packaging? To be tribal, he explains, is to favour “us” over “them,” to identify with a group culture and to fight vigorously against anything, within or without, that seems to threaten it. Political tribes are divided by visions of the good, he says, and that’s a bad thing. Their package deals don’t merely serve the common interests of their members but also try to remake the social world according to the tribe’s idea of what is right and good. They oppose each other by taking an uncompromising stand.

When ethics becomes tribal, Mumford says, people find it increasingly difficult to make compromises. Members of a tribe are expected to accept ethical positions simply because they are markers of tribal identity. The possibility of disagreement and dissent is undermined, precluding rational arguments about what ought to be valued and which positions are compatible with those values.

Two questions are likely to occur to anyone who reads Mumford’s diagnosis. First, why should we believe that ethical packaging is so prevalent in political and social life? His book is written with US politics in mind and he admits that Americans divide along political lines over issues that people in other countries don’t find so divisive. Many Australian conservatives support the gun control legislation brought into existence by a Coalition prime minister. Other issues, though more likely to divide people along political lines, are far from being part of a package. Sexual liberation is identified by Mumford as an issue that divides the left from the right, but many feminists support bans on sexual relations between those in a position of power and their students or subordinates. Many people with strong religious beliefs oppose abortion and assisted suicide but follow the Pope in veering left on social and environmental issues. And in Australia, as in many other countries, support for assisted suicide, abortion rights and gay marriage doesn’t come only from the left. Public opinion polls and the referendum on gay marriage demonstrate widespread support across the political spectrum.

The second question is whether the polarisation that Mumford deplores has much to do with ethics. Those who resist an increase in the minimum wage or more generous unemployment benefits may be motivated by class interests or simply a desire to pay less tax. Those who support assisted suicide may be thinking about what they want to be able to do when they reach the end of their life. Self-interest underneath a thin veneer of moral rationalisation may be the real driver of social division.

Mumford never really answers these questions, but that turns out to be irrelevant to his main purpose. In Vexed he mostly concentrates on what he regards as his job as a public intellectual: to challenge widely held ethical beliefs. He takes six moral positions, three commonly held by people on the left and three more likely to be held by conservatives, and argues that they are wrong, or at least more questionable than their proponents suppose.

People on the left, he argues, ought to join conservatives in rejecting assisted suicide. They ought to have doubts about sexual liberation and the pro-choice position on abortion, and about genetic enhancement. Conservatives ought to favour gun control and higher wages for workers. They ought to oppose restrictions on the civil rights and opportunities of ex-prisoners.

Mumford is good at making an ethical case. His arguments are clear and cogent. He makes good use of empirical data and jars readers out of their dogmatic assumptions by means of thought-provoking case studies. Readers who hold the views that he opposes will indeed be challenged. Two examples illustrate his method for attacking ethical packaging.

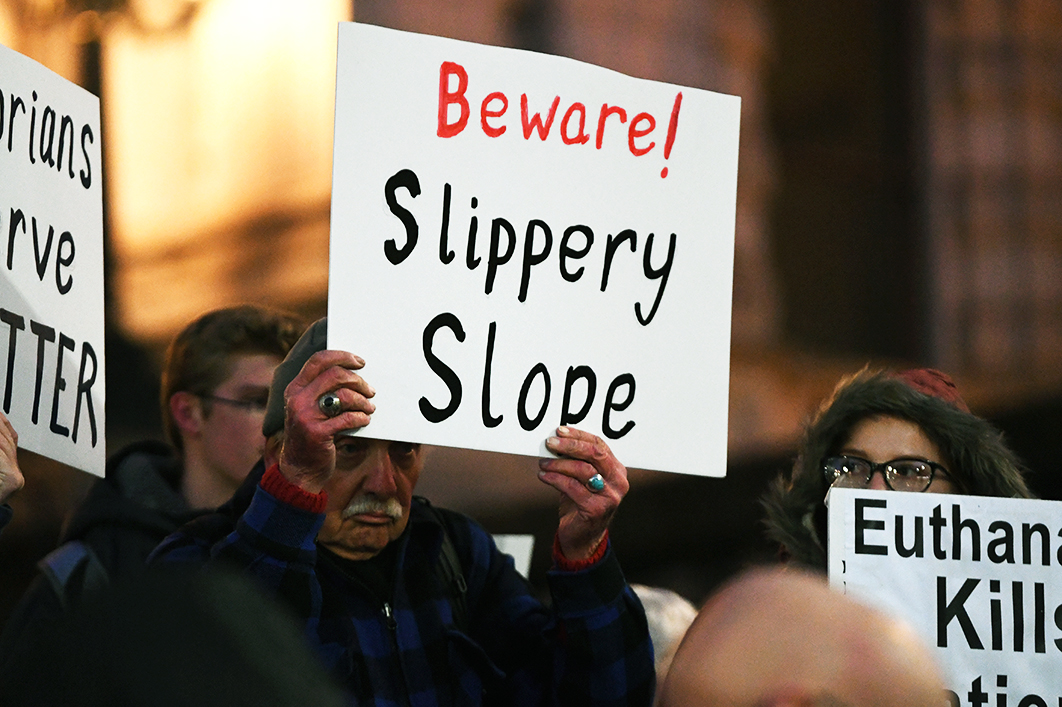

A basic value for people on the left, he thinks, is inclusivity: a commitment to protecting the vulnerable and defending the marginalised. This value, he argues, is not compatible with support for a “right to die.” To legalise assisted suicide, he thinks, is to ignore the interests of some of the most vulnerable and marginalised people in our society — the aged — who are especially vulnerable because our society, unlike more traditional communities, treats them as unproductive burdens.

Once assisted suicide becomes legal, he thinks, remaining alive will become a choice that elderly people will have to justify. Negative social attitudes towards the aged will persuade many of them to conclude that they have no justification. Mumford doesn’t think that restrictions on access to assisted suicide — like those in force in Victoria — will hold back the right-to-die push for very long. Inevitably, eligibility for assisted suicide will be extended first to the chronically ill and then to those with serious mental health issues, until it seems legitimate to allow any elderly person who is depressed and thinks he or she is a burden to take this option (as he believes is now the case in the Benelux countries). Best not to start down this slippery slope. Those on the left, indeed anyone who regards inclusivity as a primary value, ought to oppose assisted suicide in any form. It should not be part of their ethical package.

Conservatives believe in family values. Because they regard the family as the moral backbone of society, they are rightly worried about high rates of divorce and family separation. But Mumford thinks they wrongly put the blame on cultural factors — on a lack of commitment to marriage or the selfish desire of individuals for personal fulfilment. The “cultural poverty thesis” is a part of the conservative package that he wants to challenge. He cites empirical studies suggesting that the primary reason for family breakdown is poverty. Not having enough money is stressful; it leads to bad decisions and conflict. It is not a recipe for a flourishing family. Conservatives who cherish family values and want families to thrive thus have good reason for supporting measures that help the poor. “To the extent that the Right is committed to laissez faire, to the extent that it has endorsed the evisceration of unions and resisted anti-trust enforcement, the Right has ignored its family values.”

In other chapters, Mumford argues that conservatives who believe in the sanctity of life should favour gun control, and that liberals who criticise consumerism should have doubts about sexual liberation. Those on the left who profess reverence for nature should be against genetic enhancement and those on the right who stress the importance of personal responsibility shouldn’t deny ex-prisoners civil rights or prevent them from obtaining opportunities that could give them a new start in life.

Mumford naturally hopes that readers will be convinced by his arguments and accept his conclusions. If they do, ethical packages will no longer exist. What’s more, liberals and conservatives will find themselves in agreement on many issues. Everyone, he thinks, ought to value inclusivity, the sanctity of life and family relationships. Everyone ought to be critical of consumerism and revere nature. If people with different political identifications can be persuaded to reason consistently, they will often reach the same conclusions. The tribalism that plagues political life will disappear and Mumford will no longer be vexed.

Unlikely? I suspect so. Conservatives have a view of the good that is different in significant respects from that of people on the left. Political divisions are not likely to be healed by Mumford’s attempt at reconciliation. Moreover, those who favour assisted suicide or legalisation of abortion and those who oppose government intervention to decrease economic inequality have many arguments at their disposal and a complex system of values. They will find ways of countering Mumford’s reasoning. Despite his best efforts, ethical views will continue to come in packages.

But ethical agreement and the unpicking of ethical packages are not crucial to Mumford’s campaign against tribalism. What he really wants is not an agreement with all of his views, which he must realise is unlikely, but a revival of ethical conversation. He wants people to think about what they should value and whether their positions on moral issues are compatible with their values. If they are willing to engage in this exercise then they must admit that their views could be mistaken. They must be prepared to surrender or modify their positions and to accept the existence of dissent and disagreement. They must try to understand and appreciate the views of their opponents. Their ethics can’t be tribal.

Nevertheless, Mumford’s attempt to force people to reason about their values might risk treating the symptoms of political tribalism and failing to engage with the real causes. If the forces that divide people result from their allegiance to a party, a cause or a person, then an appeal to common values or ethical consistency is likely to have little effect. True believers will always find reasons, however questionable, to support their ethical positions. They will always be inclined to think that the positions of their opponents are morally pernicious. Reason, as Hume said, is the slave of the passions. Something more is needed. Mumford realises this and calls it “moral imagination.”

Moral imagination, Mumford tells us, is a sympathetic appreciation of the needs of others. It requires attention to hidden suffering — for example, the suffering of old people shut away in nursing homes. It asks us to consider the plight of future generations and the needs of people in other countries. Moral imagination, he says, is a form of cosmopolitan sympathy; we have to learn to care about people whoever they are and however distant they are from us in space or time. Cosmopolitan sympathy does not mean giving up a special concern for members of our family or nation, he assures us. We would be deficient as moral agents if we thought only about distant people and ignored poverty and suffering on our doorstep. But we need to broaden our sympathies and direct them especially to those who are poor and oppressed.

Mumford thinks that moral imagination will make us more inclined to accept the positions he argues for in his book. He also thinks of it as a cure for tribalism. If people have a sympathetic appreciation of the needs and suffering of others, then some causes of division will simply disappear. There is no room for racism, sexism or homophobia in a cosmopolitan moral order. And other causes of division will be mitigated by mutual appreciation and sympathetic understanding.

This is Mumford’s remedy for tribalism: rational argument bolstered by the exercise of moral imagination. But is it likely to work? From the perspective of moral philosophy, a lot of conceptual work obviously needs to be done in order to resolve the conflicts inherent in a cosmopolitan ethics. But the more serious difficulty is persuading people to satisfy its demanding requirements. Mumford thinks we are capable of being cosmopolitans. He believes that human nature need not get in the way, that we are not irrevocably tribal. He ends with an expression of hope. “We must begin by believing in ourselves again.” •