Before the election, I wrote a whole bunch of posts for my newsletter Noahpinion about why it was a bad idea to elect Donald Trump. But sadly, America elected him anyway. After he won, I wrote a post outlining a best-case scenario for Trump’s second term. The optimistic scenario was that Trump’s threats to enact harmful policies and cause chaos were mostly bluster, and that in the end he’d end up just waging a bunch of culture wars instead of wrecking the economy and gutting US institutions.

We’re only two weeks into Trump’s presidency, and that optimistic scenario is looking more and more remote by the day. Trump is creating a lot of institutional chaos, and I’ll talk about that in a bit. Today I’m going to talk about Trump’s main economic policy: tariffs.

In Trump’s first term, he enacted a bunch of tariffs on China and a few tariffs on specific products like steel and aluminium from a variety of countries. This ended up raising prices very slightly for American consumers, but otherwise having little effect on the nation’s economy, manufacturing sector, or trade deficit. Why? As I see it, there were three basic reasons.

First, the tariffs weren’t actually that high or that broad in terms of which countries and products they affected. Second, China rerouted some of its exports through third countries like Vietnam. And third, the tariffs caused the US dollar to appreciate and the Chinese yuan to depreciate, which cancelled out maybe about one-third or more of the intended effect.

I think that benign experience gave a lot of people a sense of complacency. If Trump kept tariffs narrow and symbolic, they probably wouldn’t hurt US households by an appreciable degree, and targeted tariffs on Chinese strategic tech products would even help us in the military–industrial competition with our main rival.

But it was not to be. Trump just announced 25 per cent tariffs on all products from Canada and Mexico (except for a 10 per cent tariff on Canadian energy imports), as well as a 10 per cent tariff on products from China. He followed this up with a promise to impose tariffs on the European Union. This is very different from his first-term tariffs, for two reasons. First, they’re on a far broader set of products than before. And second, these tariffs mainly strike at US allies instead of at a US rival.

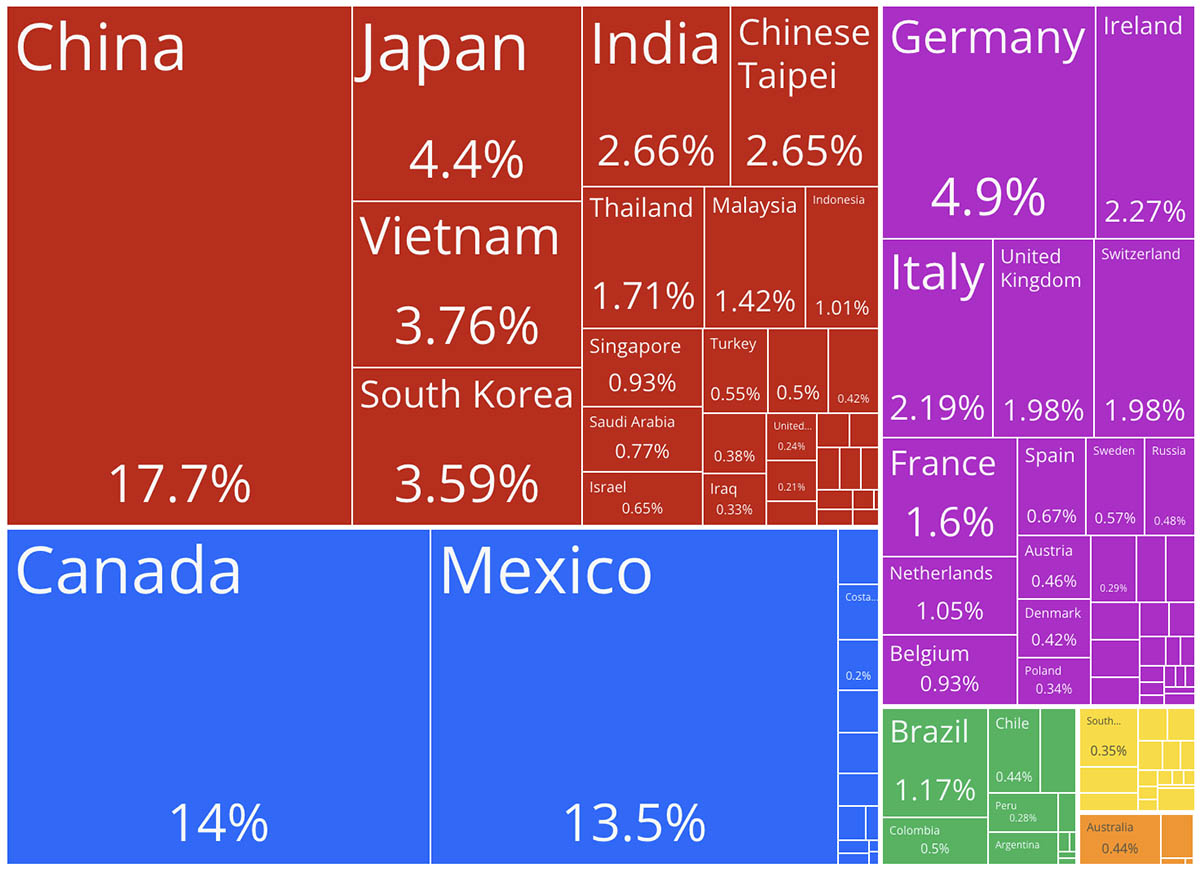

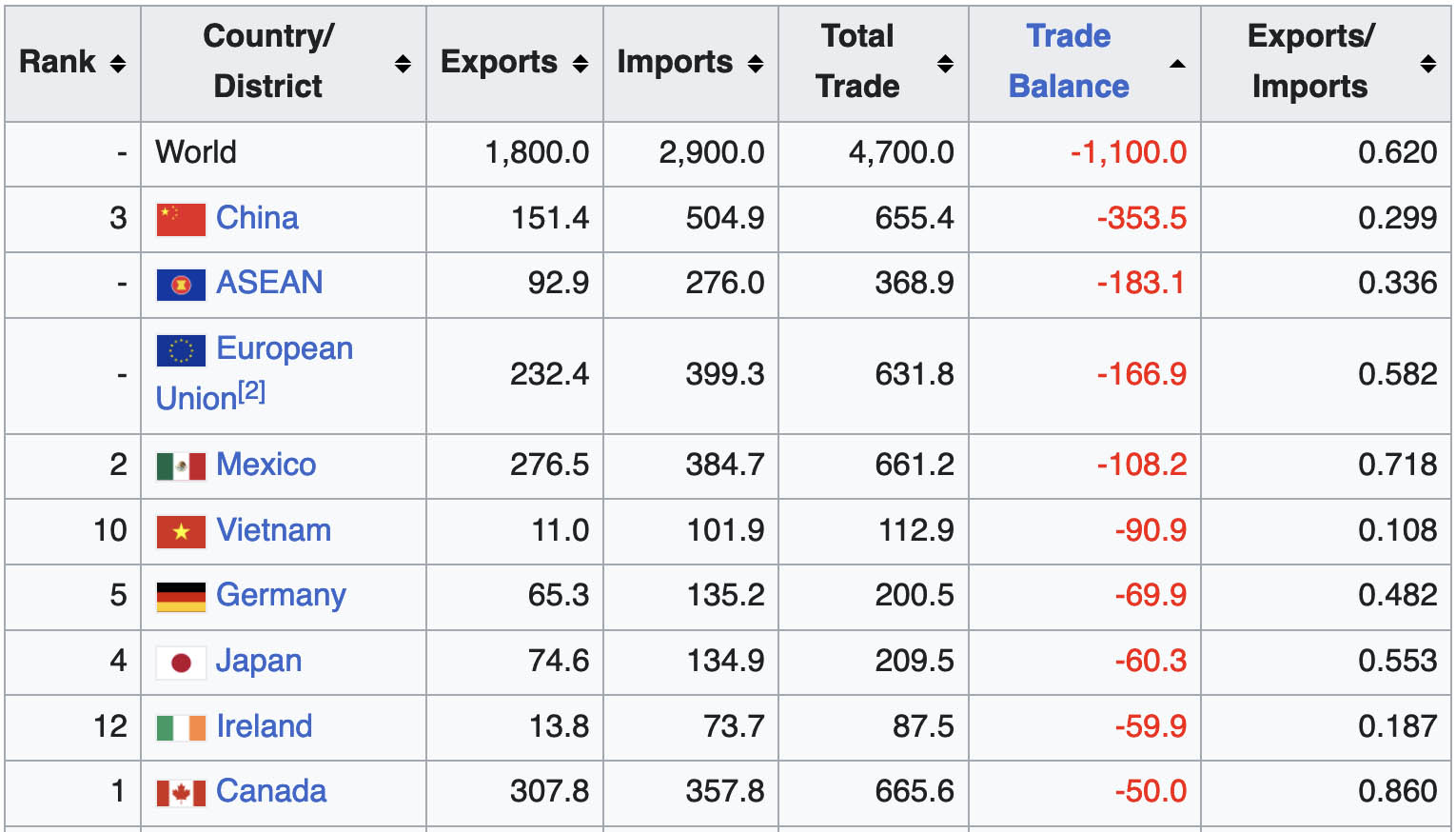

The second part of this is worth remarking on. It’s part of a larger pattern of Trump attacking friendly nations. As with his aggressive rhetoric toward NATO countries, he seems to feel deeply that America’s allies are taking advantage of us, and need to be brought to heel. But it’s striking that Trump’s new 10 per cent tariffs on China — the focus of his first-term trade war — are so much less than his tariffs on Canada and Mexico. In his first term, Trump talked about reversing trade deficits, but America’s deficit with Canada and Mexico together is less than half of its deficit with China:

Source: CIA via Wikipedia

It seems reasonable to worry that the Chinese Communist Party may have succeeded in gaining a measure of influence over Trump.

As usual with Trump’s tariffs, there’s the possibility that he’ll remove them once the targeted countries comply with some demand or make some symbolic concession. But it’s not yet clear what Trump actually wants from Canada and Mexico. His tariff announcement talks about illegal immigration and fentanyl:

The extraordinary threat posed by illegal aliens and drugs, including deadly fentanyl, constitutes a national emergency… Until the crisis is alleviated, President Donald J. Trump is implementing a 25% additional tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico… President Trump is taking bold action to hold Mexico, Canada, and China accountable to their promises of halting illegal immigration and stopping poisonous fentanyl and other drugs from flowing into our country… The orders make clear that the flow of contraband drugs like fentanyl to the United States, through illicit distribution networks, has created a national emergency, including a public health crisis… There is also a growing presence of Mexican cartels operating fentanyl and nitazene synthesis labs in Canada. A recent study recognized Canada’s heightened domestic production of fentanyl, and its growing footprint within international narcotics distribution.

So it’s possible that if Mexico agrees to crack down on illegal border-crossing and Mexico and Canada both agree to take some sort of action to crack down on fentanyl, Trump will lift the tariffs. These actions might be substantive, or they might be purely symbolic, like China’s concessions in Trump’s first term (which of course it reneged on).

If Mexico and Canada get Trump to drop tariffs by taking symbolic actions, it will seem to justify the belief that Trump is all bluster and smoke, and that all he really wants is to force other countries to bend the knee and acknowledge his power. This would be distasteful, but it’s clearly the best possible outcome for both Americans and for the people of Canada and Mexico.

But even in that best-case scenario, the uncertainty generated by this policy will be considerable. American businesses that rely on imports from Canada, Mexico and other US allies — including many manufacturers — won’t be able to make long-term plans about sourcing. And American businesses that rely on exports to Canada, Mexico and other allies will have to worry about future trade wars and future retaliations. Uncertainty is bad for business and generally bad for the economy.

But if Trump keeps the 25 per cent tariffs on Canada and Mexico in place, it will be a very significant policy. Although Canada and Mexico are responsible for less of America’s trade deficit than China, they’re responsible for much more of our total imports:

Economist Brad Setser has made some back-of-the-envelope calculations showing that the new tariffs are more than twice as big as Trump’s tariffs during his first term — even before adding in potential additional tariffs on the European Union. Things are starting to get serious.

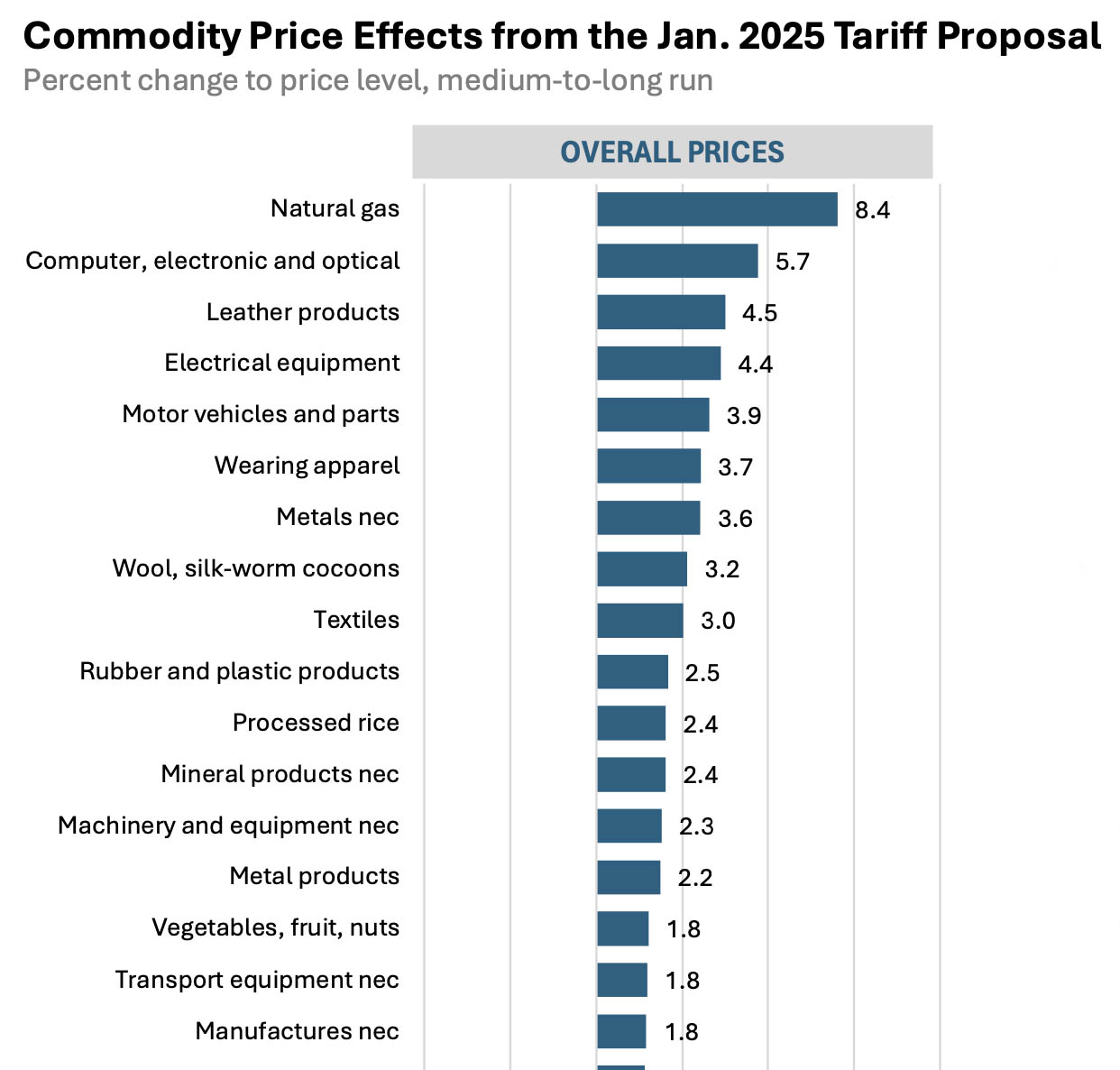

What harms could the tariffs do? Well, the most obvious one is that they’ll raise prices for American consumers. The Yale Budget Lab has some estimates of how much these tariffs will increase prices for various goods in the US, and while it’s not catastrophic, it’s also enough to be noticeable. Here’s a truncated version of their chart:

Source: Yale Budget Lab

What’s more dangerous is if these price increases manage to reignite inflation expectations. Already, market expectations of inflation over the next five years have risen since it became likely that Trump was going to win the 2024 election. They now stand at 2.5 per cent — still not super high, but generally higher than over the last two years.

If inflation expectations go higher, it could cause a self-fulfilling prophecy where businesses raise their prices in the expectation that other businesses will do the same. That would force the Fed to either raise interest rates or accept higher inflation. And it could make Americans very angry.

(Exchange rate appreciation, of course, will cancel out some of the impact of tariffs — maybe a third or even half. But a stronger dollar has the downside of making US exporters less competitive.)

And the negative consequences go well beyond consumer prices. American manufacturers could be severely hurt by the disruption of their supply chains. When I wrote about the problems with broad tariffs back in November, I pointed this out:

Broad tariffs also raise costs for American manufacturers, without increasing costs for Chinese manufacturers.

Consider the market for cars. Car companies use a lot of steel and aluminium to make cars. When steel and aluminium get more expensive in America, that raises costs for American car companies. That makes them less competitive, both in the domestic market and abroad.

So if the US puts broad tariffs on everything we import, that will include steel and aluminium. GM and Ford and Tesla will be paying higher prices for steel and aluminium because of the tariffs, so they’ll have to raise the prices of their cars. But BYD and other Chinese car companies won’t have higher costs, because the tariff only applies in America. So the Chinese car companies will gain a competitive edge against the American car companies. That will make Chinese car imports cheaper and American car exports more expensive.

In fact, we have good evidence that this happens. Lake and Liu (2022) studied the effects of Bush-era tariffs on steel and aluminium, and found that they hurt steel-consuming industries like the auto industry… Across-the-board tariffs make US-made cars and semiconductors and washing machines and refrigerators and farm equipment and robots more expensive, because they raise the cost of imported inputs like steel, aluminium, photoresist, batteries, and so on. But foreign-made products can still get cheap inputs, because they aren’t paying tariffs.

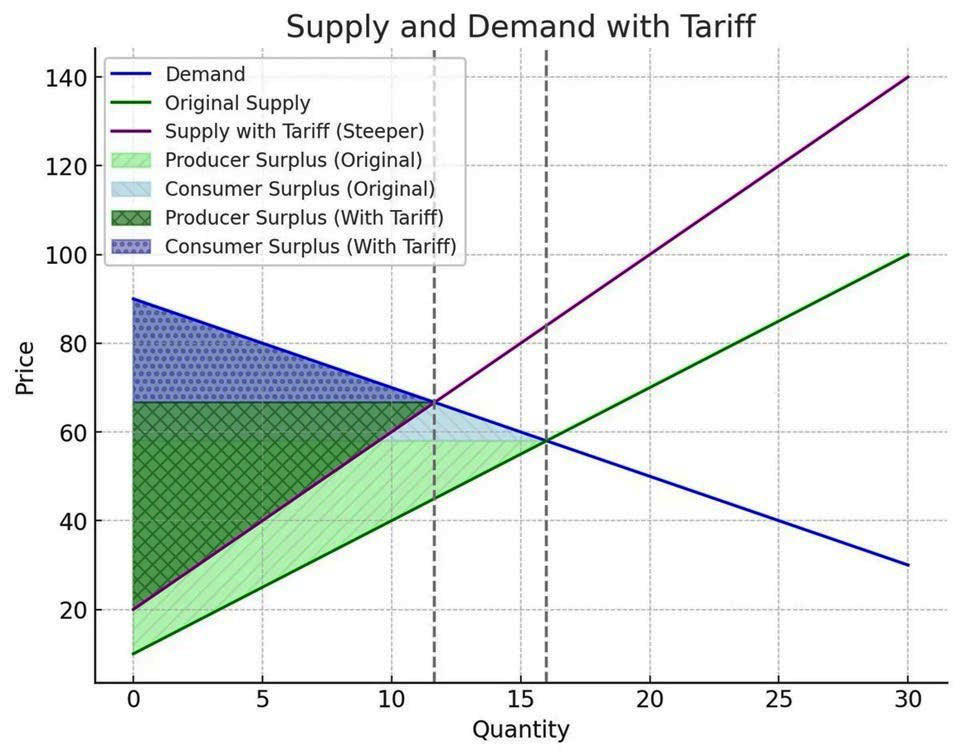

Brian Albrecht has a good post explaining this in basic Econ 101 terms. Some excerpts:

As I’ve explained before, one implicit assumption in this argument is that trade is in finished products for consumers. But a large part of international trade occurs in intermediate inputs and components, not finished products ready for consumers. Companies import parts, materials, and unfinished goods to use in their own production processes. This means tariffs often act more like a tax on domestic manufacturers who use these imports, raising their costs instead of protecting them from foreign competition…

[R]esearch by Handley, Kamal, and Monarch examining the 2018–19 US tariffs — which included duties on solar panels, washing machines, steel, aluminium, and a wide range of Chinese imports — found that products more exposed to tariffs on imported inputs experienced significantly lower export growth. This effect was equivalent to foreign countries imposing a two percent tariff on US exports. On average, exports of unaffected products grew two percentage points faster than affected items. The tariffs intended to protect domestic industries ended up acting as a tax on US exporters, undermining their global competitiveness.

In fact, the real situation is even more complex than Brian’s simple model suggests, because many of the intermediate goods the US imports from Canada and Mexico are themselves made using US exports. Automakers have stated that if the tariffs go into effect, it will shut down a lot of automotive production on both sides of the Canadian and Mexican borders. Supply chains are a delicate web, and if you want to smash them with tariffs, you better have a good reason for doing so.

For China, national security might provide us with such a reason; fentanyl labs across the Canadian and Mexican borders are not one. Trump’s new round of tariffs has been roundly condemned by pro-business voices such as the US Chamber of Commerce, Tyler Cowen, and the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board. The WSJ called it “the dumbest trade war in history.”

I’m not sure if that superlative applies, but it’s certainly America’s dumbest trade war in living memory. There’s really no upside for the country here — it’s not going to help domestic manufacturing, it’s not going to make Americans better off, it’s not going to materially affect the fentanyl problem, and on top of all the economic risks it’s going to piss off US allies and make America look terrible.

I still hold out hope that the tariffs will be quickly revoked after some sort of symbolic concessions. But if not, then we’ll know that we’ve left the era where Trump just blustered and preened, and entered a more frightening era where he starts lashing out and breaking things. •