DESPITE the usual diplomatic niceties at the celebration of the thirty-eighth anniversary of Timor-Leste’s declaration of independence in Canberra last week, the raid on that nation’s legal counsel in Australia, Bernard Colleary, probably says more about the current state of the relationship between the two countries. It may be true, as attorney-general George Brandis asserts, that ASIO was more interested in preventing the potential identification of Australian intelligence activities and identities than in undermining the forthcoming arbitration in The Hague over an oil revenue sharing treaty. In practice, however, it is difficult to peel those two apart. This is especially so given that Timor-Leste’s star witness in the arbitration – an ASIS agent turned whistleblower – has had his passport removed, an act that will inevitably affect the presentation of Timor-Leste’s case.

The key allegation is that Australian intelligence operatives spied on the Timorese negotiating team in 2004, and that the surveillance was aimed at securing a commercial advantage in revenue-sharing talks. Especially damaging is the allegation that the exercise involved planting listening devices under the guise of an aid project to renovate government offices, rather than the use of more routine communications surveillance, which – though damaging – might more easily be represented as incidental to a security purpose. This raises wider issues about the regulation of intelligence agencies, the opaque enforcement of these laws, and the lack of adequate independent judicial oversight.

The possibility that AusAID may have unknowingly been used for intelligence-gathering activities is very disturbing, and raises concerns over the ability of that agency to function free of suspicion in the region. Former foreign minister Alexander Downer was dismissive of these allegations as “old news,” though his current role as a lobbyist for Woodside Petroleum does little to inspire confidence in his commentary.

In Timor-Leste itself, where it is seen as a matter of national sovereignty, the controversy has united the often-fractious political parties. It should first be understood that Australia and Timor-Leste still have no settled maritime boundary. However, a complex series of revenue-sharing agreements has allowed some oil and gas developments to proceed. The complicated history of how that situation arose helps explain why tensions are so high at the moment.

In 1972, Australia settled a very favourable deal with Indonesia on maritime boundaries, based on “continental shelf” principles that were little favoured in international law at the time, and are scarcely credible today. As a result, the boundary was much closer to Indonesia than to Australia. Portugal – then the administering colonial power in East Timor – refused to join the negotiations, preferring to wait for the international process which, in 1982, resulted in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS. Portugal’s decision created the “Timor Gap” in the Australian–Indonesian sea boundary. In 1989, Gareth Evans famously sealed a deal with Indonesia for joint exploitation of oil and gas in the Timor Gap and for 50–50 revenue-sharing in the “Zone of Cooperation.” Such an agreement depended on Australia being the only Western nation to offer de jure recognition of Indonesia’s forced annexation of East Timor. Portugal challenged that treaty in the International Court of Justice, but the action lapsed in the face of Indonesia’s refusal to recognise the court’s jurisdiction.

With the restoration of East Timorese independence in 2002, these arrangements had to be renegotiated. In the meantime, international law had sharpened considerably. Since the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982, standard international practice has been for maritime boundaries to be established at the median point between nations. This is not an idealist principle of international law, emanating abstractly from Geneva or New York, but a specific convention to which Australia voluntarily acceded in 1994.

Australia withdrew from the maritime boundary dispute resolution procedures of UNCLOS, and the equivalent jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, two months before the restoration of East Timorese independence in May 2002. These unilateral actions – which showed little confidence in the strength of the “continental shelf” argument – left Timor-Leste without the option of international arbitration. The withdrawal was conducted in secret, with the Australian parliament only informed after the reservations took effect.

After independence, a section of the old Zone of Cooperation, now renamed the Joint Petroleum Development Area, or JPDA, was renegotiated to give Timor-Leste 90 per cent of revenues. Though this might appear generous at first blush, Timor-Leste had a respectable claim to the entire area, and the JPDA notably excluded other existing fields, such as Laminaria-Corallina and Buffalo. The JPDA’s lifespan is limited, moreover, and the picture was complicated by subsequent negotiations over an undeveloped field – Greater Sunrise.

Under the next in the series of treaties, the Sunrise International Unitisation Agreement, 20 per cent of that field was declared to be within the JPDA boundary – giving Timor-Leste rights to only 18 per cent of its total revenues under JPDA principles. The subsequent and now contentious Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea treaty, or CMATS, then did two things: it increased Timor-Leste’s share of upstream revenues in Greater Sunrise to 50 per cent, but on condition that permanent maritime boundary negotiations were delayed for fifty years. Though Timor-Leste acceded to the treaty in 2007, it is worth noting that it didn’t have the option of an arbitrated settlement: Australia’s withdrawal from two international dispute resolution jurisdictions put the negotiations outside the realm of international law and firmly in the realm of power politics. A median-point maritime boundary determination would see a far larger percentage of these resources in Timor-Leste’s exclusive economic zone.

Timor-Leste has since been in a standoff with Woodside Petroleum, whose preference for a floating LNG processing facility in the Timor Sea clashes with the Timorese desire for a processing facility on Timor’s south coast, to boost development of that region. Regardless of the merits of that plan – and they are in some respects debatable – the Timorese leadership is united in that position. Although Timor-Leste or Australia had the right to suspend the treaty in February 2013 if a Greater Sunrise development plan had not yet been approved, the revenue-sharing and boundary-moratorium provisions in CMATS would come back into force whenever the field is developed. This, in effect, made certain aspects of the CMATS treaty irrevocable.

The significance of the current arbitration is that Timor-Leste is seeking to have the treaty nullified under the wider principle, codified under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, that negotiations should take place in “good faith.” Although the world of realpolitik promotes cynicism about such concepts, the issues here are now quite stark ones. If Australia was spying on the Timorese negotiating team, the issue of good faith is already in question. If it could be established that Australia was doing so for the purposes of gaining unfair commercial advantages, for Treasury itself, or for Woodside Petroleum, the question becomes all the more pertinent.

THIS is a difficult path for the young nation. If CMATS is annulled, negotiations over the maritime boundary could resume, but the former treaty – which gives Timor-Leste only 18 per cent of Greater Sunrise revenues – would effectively prevail in the meantime. To some, the contest over CMATS might also raise fears about the sovereign risk of investing in the Timor Gap, though the Timor-Leste government would counter, with considerable justification, that it has not abrogated any treaty and is merely using dispute-resolution provisions that Australia signed and ratified. Importantly, from the Timorese perspective, a permanent maritime boundary offers the prospect of increasing Timor-Leste’s share of the only resource available in the short term to deal with massive issues of poverty, illiteracy and underdevelopment. This issue is becoming totemic of national sovereignty.

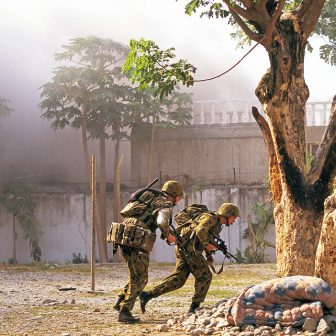

For the Australian government, the risks are less obvious. A good relationship with Timor-Leste is certainly at stake, and those cynical about its importance might reflect on the failure of Julia Gillard’s “East Timor solution.” The court of Australian public opinion is another issue. The public is relatively well-informed about East Timorese people’s support for Australia’s Sparrow Force during the second world war and Australia’s subsequent abandonment of the East Timorese until 1999. The Australian government’s leadership of the INTERFET mission is widely viewed as an historical corrective, and a source of pride for Australians. It is unlikely that the public wants to see this tarnished by unfair treatment of Timor-Leste’s finite oil and gas revenue base.

Australians are also unlikely to be impressed that Australia withdrew from the two maritime boundary dispute resolution mechanisms in 2002. That Australia then settled its maritime boundaries with New Zealand along median lines only two years later in 2004 is less well-known at present. A new campaign is likely to highlight this, and public questions will be asked about the differing standards applied. Any evidence that Australia extracted an unfair commercial advantage during treaty negotiations could further undermine public sympathy.

Another path is possible in the negotiated settlement of maritime boundaries in good faith, which would remove the major irritant in the relationship for good. If this approach is adopted, Australia may well find Timor-Leste willing to negotiate transitional arrangements over existing and future oil and gas wells in its waters, providing for commercial certainty and, potentially, continuing revenue-sharing, on fairer terms. •