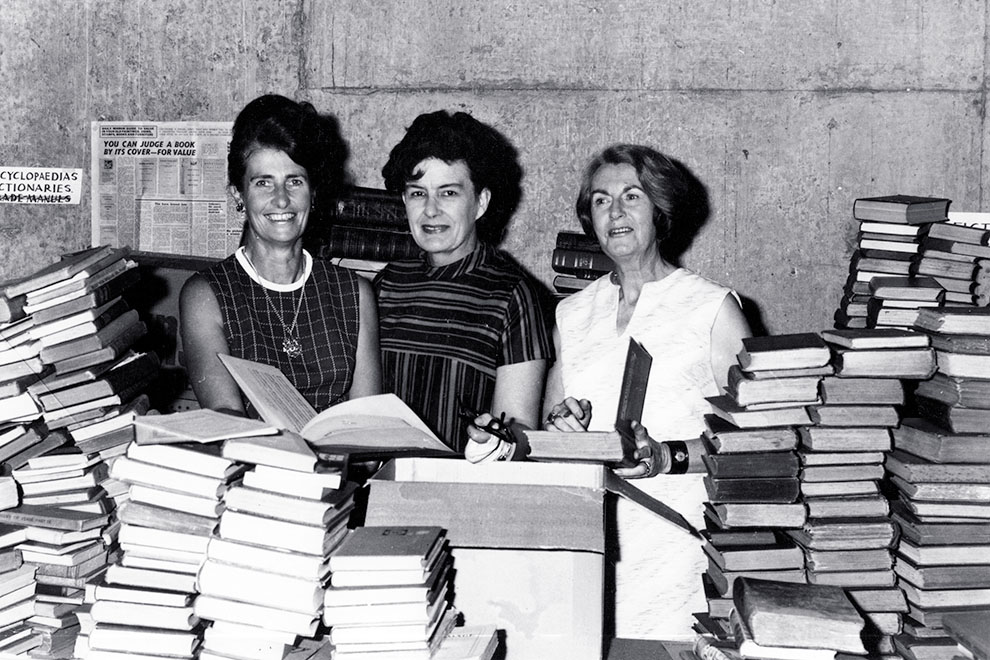

Fugitive Books: The U Committee’s Book Fair 1968-2012 & Women’s Voluntary Work at UNSW

By Roderic Campbell | UNSW Archives | $25

Basser, Philip Baxter and Goldstein: The Kensington Colleges

By Claire Scobie | UNSW Press | July 2015 | $49.99

For weeks there’s been an untidy pile of old books in the corner of the front verandah. They are waiting to be sorted, packed and stored for the coming book fair, but as soon as I deal with this lot the pile will grow again. Our book fair is a modest one-day event. Books are roughly sorted and laid out on tables in the hall, priced mostly at $2 each. Even so, we usually raise about $8000 to $10,000 for community projects.

By comparison, the book fair at the University of New South Wales that is the subject of Roderic Campbell’s Fugitive Books was much more ambitious and became almost professional in its organisation. It was begun in 1968 by the U Committee, an offshoot of the University Wives Group, as a way of raising money for fittings and furniture for International House, a residential college being constructed at the university. Initially run every second year over several days, towards the end it became an annual event and had become a massive effort undertaken with diminishing resources. Not only had the university itself changed, but the wives group itself had become an anachronism and folded in 1993. The women themselves were ageing, even dying. Many of the younger wives now had careers and neither time nor need for a wives group or a book fair. As well, the introduction of the GST had placed an unwelcome burden on the accounting practices of the U Committee.

Much of this painstakingly researched and written story of the UNSW book fair is about the changing role of women as volunteers and fundraisers for a new university without sustaining networks, bequests or traditions. Initially the wives group was established because so many of the staff were new to the university, to Sydney, even to Australia. While working relations were quickly and easily established among the male academics, their wives often felt isolated or lost. The wives group helped the women to make friends. Without the kinds of resources – social, financial or institutional – such as had grown over time within older universities, it was logical that the women should then busy themselves with raising money to pay for the kinds of things funded elsewhere out of gifts and bequests; hence, the U Committee and eventually the book fair.

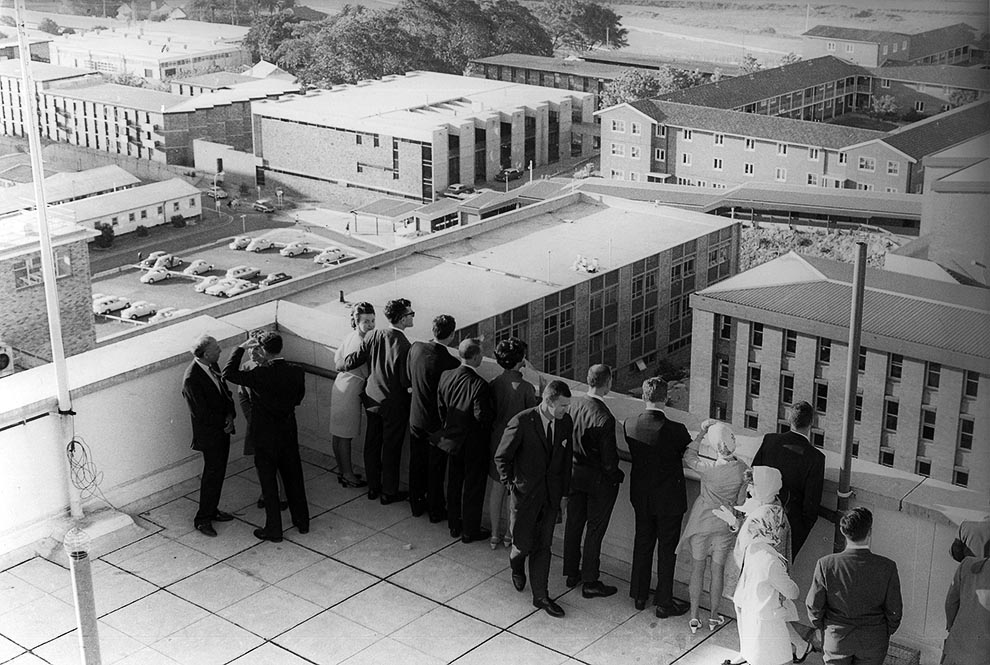

Claire Scobie’s Basser, Philip Baxter and Goldstein: The Kensington Colleges tells a similar story of maturation. The only residential accommodation available to students at the University of New South Wales when it was created out of Sydney Tech in 1949 was in ex-army huts. In 1959 the stark shape of Basser College, perched high on the sandhills above the earliest university buildings, opened for its first intake of students, all young men. Goldstein followed nearby in 1964 with provision for some women students, and Baxter in 1966 was co-ed from the start. Two successful immigrant businessmen, Adolph Basser and Philip Goldstein, made generous gifts in return for naming rights and governments provided matching funding to the university in the then widespread belief that residential accommodation was a desirable adjunct to university education. All were secular, as was International House, opened in 1968. Over time the spartan conditions of the Kensington Colleges came to be considered inadequate. Vice-chancellor Rory Hume commented after a visit to Baxter in 2004, “You wouldn’t put prisoners in here would you? I’d be very happy to be the first to come along with a sledge hammer to knock it down.” And indeed, a decision was taken, not long after, to demolish and rebuild the colleges more in accord with modern ideas of adequate accommodation.

Max Dupain’s photo of UNSW alumni viewing the university from the top of the Civil Engineering building on 25 October 1968, from Basser, Philip Baxter and Goldstein: The Kensington Colleges. Courtesy UNSW Archives

Judging by the comments of many of the former “inmates,” however, their time in the colleges was memorable, valued and effective in enhancing their education. In general, though they often condemned the quality of the catering, defects in the accommodation seemed unimportant. The decision to demolish the old buildings was not universally welcomed, and this book was commissioned as a kind of memorial to the lives that were lived within those walls. As she works though decade after decade, Scobie’s statistics show the gradual increase in the proportion of women (and an almost equivalent decline in overseas students) in the colleges. Her interviews, the memorabilia contributed by ex-students – some of it colourfully reproduced here along with a selection of photographs – and the evidence of student publications demonstrate a slow falling away of the hearty male sporting culture of the early years, with its pranks, drunkenness and childish silliness. There were debates over whether to try to emulate the traditions of older colleges or to create something new, apart from the ever-present rivalry between the colleges. Unfortunately, though more humanities students joined the engineers, there does not seem to have been a corresponding rise in cultural or intellectual activity. Nonetheless, the statistics do suggest a higher than average achievement of good grades by college students, and many have acknowledged the value of contacts made, friendships that continued for life, the marriages, and other intangible human benefits of college life that cannot be quantified.

From the book fair there were many quantifiable benefits, not least the $2.43 million that went to support the purchase of art works, subsidise music, provide literary fellowships, assist student projects like the Sunswift solar car, or underwrite the university’s oral history archive. More unquantifiable benefits are suggested in Campbell’s chapters on the sociology of the book fair. He is interested in where the donated books came from, in profiling the dealers, the collectors and the huge variety of people who came in search of books. The last book fair followed a long period of gloomy discussion about the future of books and publishing in a world of computers and electronic readers.

Few things have been changed more dramatically by modern technology than the secondhand book trade now that it is possible to find and order any kind of book from almost anywhere in the world on the internet. The need to scour book fairs, garage sales and op shops for desired items has disappeared, but not, it seems, the pleasure of doing so. Many were still coming, hoping for bargains, others simply curious about what they might find. Among the real prizes were familiar titles or authors never before seen or read. Here was a copy for a couple of dollars – what was there to lose? Campbell writes engagingly of the circulation of books through the book fair with their freight of knowledge and culture, where it was the unexpected that could stimulate or entrance.

These books both suggest a kind of nostalgia for a simpler, more innocent past in which the women who worked in the bookroom did so because they enjoyed the company and being among books, while students could play sport, join clubs and invent crazy ideas and activities because they did not have to spend time commuting to the university from cheap and exploitative lodgings far away. Both tell of the gradual transformation of the university into a multimillion-dollar business that was no longer prepared to subsidise space, a phone or occasional labour for the book fair, or provide student accommodation “on the cheap.” Volunteer labour is now more trouble than it’s worth, and colleges must maintain hotel standards to attract profitable conference-goers or tourists. •