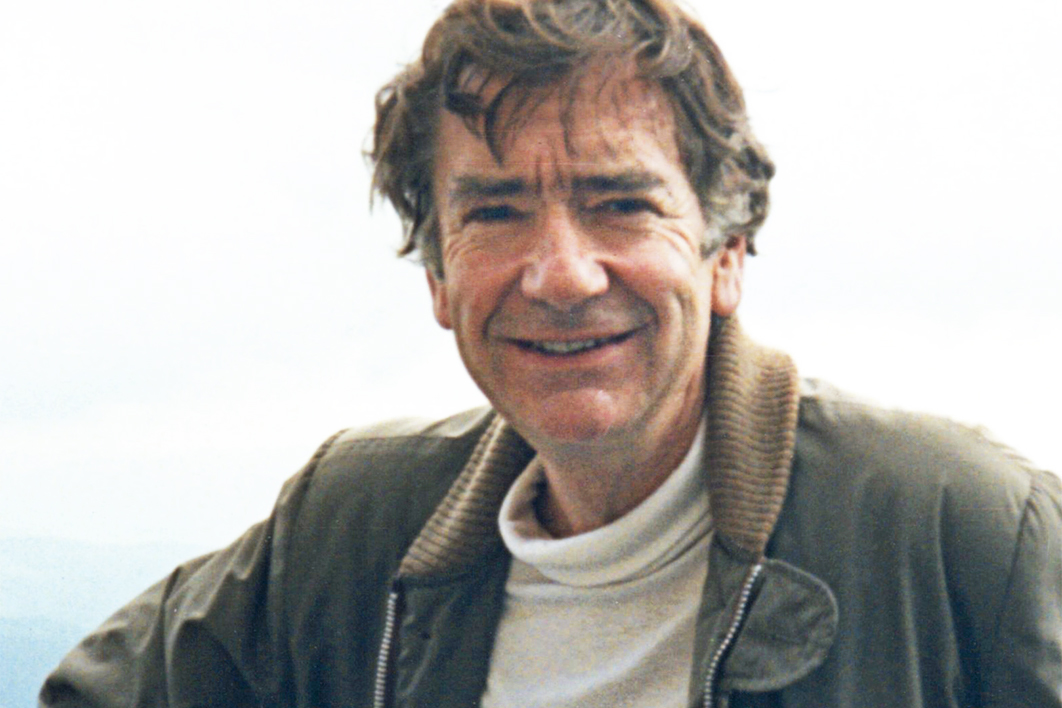

This is an edited version of Tom Griffiths’s speech at the launch of

“I Wonder”: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis

In celebrating this heart-warming, reflective and invigorating book, I will of course be talking about Ken Inglis. But I will also be talking about Ken’s family of scholars. For Ken inspired friendship, loyalty and love like few intellectuals. This book is a happy product of that affection and admiration. It is a tribute from people who knew and loved Ken, for whom he is still present, still vividly remembered and cherished. Those memories are alive and resonant, and Ken’s published words continue to inspire and win him new friends.

Like many people, I look back on four decades of Ken’s gentle, inquiring, compassionate kindness. He encouraged me in every job I’ve ever had and he responded to all my books — with postcards, letters, emails, warm words, a smile, a puzzle, some wordplay, a telling question, a review. When I voyaged south, we exchanged emails to and from Antarctica. Ken and his wife Amirah welcomed my family to ANU and Canberra, where we shared a devotion to the Australian Dictionary of Biography and its staff and to the idea of national collaborative scholarship, to the excitement of history as a vocation shared inside and outside universities.

All these endeavours were enhanced by Ken’s consideration, made more significant by his attention, nudged along by his questions, illuminated by his sweet insight. I offer this personal testimony simply because it is typical: Ken did the same for so many people, helping us to know who we are as scholars, writers and thinkers in Australia. He created a generous fellowship of like minds. It is Ken’s benevolent influence that permeates this book and that brings us together tonight.

But this book is much more than a tribute. It is scholarly, reflective, critical, contextual and expansive. The book offers a masterclass in historical thinking, intelligent living, generous scholarship, fine writing and critical citizenship. Its authors create a rich kaleidoscopic portrait of Ken, but also of the craft of history in Australia in the last seventy years. Reading and savouring this book is a great way to renew one’s sense of vocation as a historian, writer and thinker engaging with the public and situating oneself thoughtfully in one’s place and time.

Born in 1929, Ken was of a generation when his coming of age coincided with the great expansion of universities, so he was inducted early and easily into academic life — and he clearly loved it, relishing its autonomy and freedoms. But he was never just an academic, perhaps never even primarily an academic. It’s surprising to realise that about one who was so early a professor and so naturally an academic leader. But Ken’s only boyhood ambition was to become a journalist, and he almost did become one. And in some senses he always was one anyway, for it was a calling he pursued in parallel with, and sometimes against the grain of, his academic life. From the late 1950s, he was the Adelaide correspondent for the new fortnightly paper Nation; he enjoyed “moonlighting” for the paper — literally so, for the pieces were usually written in the evenings and posted at midnight.

Ken was a media junkie: he provided commentaries on the press, he was “enraptured” to be carrying a press card when he reported for the Canberra Times and Nation on the fiftieth anniversary pilgrimage to Anzac Cove, he looked for opportunities to contribute to broadcasting and he wrote histories of the ABC. He was always “looking for a way to communicate with audiences outside universities.” Ken reminisced that “I would like to be read by the people I went to school with. And by my parents. And by my children.”

His book The Australian Colonists: An Exploration of Social History, 1788–1870 (1974) was richly illustrated, designed to reach a popular readership. His leadership of the bicentennial history project, Australians (eleven volumes, 1987), and his championing of the innovation of “slice history” — which involved writing intimately about one year in people’s lives — were, among other things, experiments in writing for the broadest possible audience. And they were also a kind of provocation to his fellow academics to lift their eyes to the horizon, to imagine a public beyond the university. Inglis believed that “slicing” encouraged authors “to be more self-conscious about our prose than is general among academic authors.”

Ken studied and respected popular historical consciousness, and he championed history wherever it was done well. This was part of what drew him to love and support the Australian Dictionary of Biography and its nationwide fellowship of historians from all walks of life. Although he became a research professor, much of his own writing was commissioned: by newspapers, by urgent circumstance, by a hospital (Hospital and Community: A History of the Royal Melbourne Hospital, 1958), and by the Australian Broadcasting Commission (This Is the ABC, 1983). His work in Papua New Guinea, especially as vice-chancellor there (1972–75), demonstrated his commitment to the public role of the university in forming a new nation. He was what my generation called a public historian, but one who worked from within a university, and his sense of the university was a noble public institution not a corporate one. “Public” was an honoured word in Ken’s lexicon.

Many of Ken’s intellectual instincts and social convictions came together early in his career in his intensive, political writing about Rupert Max Stuart, an Arrernte man who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1959. Ken wrote his book The Stuart Case (1961) very quickly; it was both quality journalism and contemporary history, a courtroom drama in narrative form for a wide readership. He was a participant observer, an actor, a witness to the unfolding action, a journalist and a historian. He volunteered to be the unpaid clerk in the courtroom collating the transcript of evidence as it spilled from the stencilling machine. Thus he had what he called “a ringside seat, or rather a seat inside the ring, at the bar table.” In a compelling chapter about the case in this book, Bob Wallace and Sue Wallace explain that Ken’s writing was “a significant factor in averting Stuart’s hanging.” Ken was also embarked on an intriguing literary odyssey, for he was writing true crime — we can see The Stuart Case as an early example, if you like, of a genre of literary non-fiction with which we are now more familiar, a precursor of John Bryson on Lindy Chamberlain, Helen Garner on Joe Cinque and Chloe Hooper on The Tall Man, and even pre-dating by half a decade Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966).

Ken ended his book on the Stuart case with a reflection on civil society, comparing Australia in the early 1960s to Hungary or South Africa, and concluding that “the line from Australia to a police state is long.” “It is nevertheless,” he warned, “continuous.” The case he analysed reminded him that “the free society is a precarious achievement, depending as much on the absence of seriously divisive issues as on allegiance to liberal principles among holders of office.” One reads those words in Australia in 2020 with a frightening realisation that something has now broken, that we are much further along that continuous line than when Ken wrote. Historians should — and I think do — monitor that continuum, registering slippage in contextual detail; otherwise we lose our freedoms without realising it and miss the chance to fight for them. This is another way in which the work of Ken Inglis continues to inspire us.

Sometimes Ken’s journalism was in tension with his work as an academic and his standards as a historian. Following his reportage on the Stuart case, conservatives on the University of Adelaide council attempted to block his promotion. And when he tried to write the fiftieth anniversary Anzac pilgrimage as a book of history, he baulked at what he could not bring himself to say. Bowing to the sensitivities of the diggers might be acceptable in his journalist’s dispatches from the Mediterranean, but not — he felt — in a considered history of the event. Martin Crotty tells this story in the collection under the title of “The Book That Never Was.”

Ken’s habit was to be a sympathetic observer of past and present: detached, respectful and curious. His propensity for “being there,” for being a witness, underpinned his predilection for ethnography, which from the 1970s became a powerful influence on historians. As ever, Ken was ahead of the game thanks to his first wife Judy Betheras, who was an anthropologist, and also because of his eight years in Papua New Guinea living among other, very different cultures. In this collection, Shirley Lindenbaum makes the case for Ken as “an anthropological historian,” and Marian Quartly identifies his bicentennial “slicing” — with its explication of time and its focus on the texture of everyday life — as an invitation to ethnography.

As an undergraduate, I was taught by Greg Dening who, like Ken, drew inspiration from the writings of the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Also like Ken, Dening regularly observed Anzac Day, taking his students to the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance to practise ethnography. Graeme Davison was there too at the dawn service, and one can see how an interest in monuments and ceremonies, ritual and language, the topography of time and space, illuminated the work of these three great historians. Graeme writes about “Ceremonies of Life and Death” in this book, and explores Ken’s quest to understand Australia’s distinctive “civil religion” and the sense of the sacred built around the war dead, a mission that culminated in Sacred Places (1998).

Ken’s interest in monuments and ceremonies was what attracted me to him, and our first exchange was about observing Anzac. Although we had not yet met, I sent him my account of Anzac Day in Beechworth in 1979 and he replied with a succession of encouraging postcards. He introduced me to his friend Stephen Murray-Smith, who published my essay in Overland. The Anzac Day that I described as a twenty-one-year old was both meaningful and melancholy, a poignant dying ritual, and the diggers I spent the day with knew that the event would die with them: “it would dwindle away eventually, this Anzac business. It was sad to think so, but the young people of today don’t really understand what it’s all about, they don’t realise the hardships.” Yet within a decade the ceremony was resurgent. As Bill Gammage writes in this collection, he and Ken didn’t foresee that reinvigoration either. One of the fascinations of this volume is the way it traces Ken’s steady, lifelong inquiry into war and society — from saluting the flag at North Preston State School in the 1930s to the publication of “The Anzac Tradition” in 1965 to The Australian Colonists in 1974 to Sacred Places in 1998 to Dunera Lives in 2018 and 2020 — all played out against a rapidly changing landscape of modern Australian warmongering. In the 1960s Ken set out to rewrite Australian history by working backwards and forwards from the Anzac landing in 1915; yet while he was writing during the 1970s, 80s and 90s, Anzac Day was itself changing. This is the double dance of the historian and Ken maintained his balance with elegance and grace.

One of Ken’s subtlest and most enduring influences on Australian historical scholarship came through his love of language. He was a lucid, precise, wonderful writer who took the linguistic turn early and encouraged close attention to the history of words. In 2007 he gave a brilliant Allan Martin Lecture at ANU on Speechmaking in Australian History, beginning with the words “Men and Women of Australia!” In the course of his own speech, he “turned for enlightenment to Benjamin Franklin and Monty Python” and confessed that like most academics (and perhaps most Australians) he was “nearly all voice and no body.” The 2016 gathering in honour of Ken upon which this book was based was called A Laconic Colloquium, and Craig Wilcox in Observing Australia (1999) called him “a vernacular intellectual.” Jay Winter ends this book with an essay about “Ken Inglis and the Language of Wondering,” where he gives thanks for “the rhetorical posture of his prose,” the leaning back, the sympathetic gaze, the quizzical expression of “I wonder.”

For years, I used a 1990 essay Ken wrote on “Historians and Language” in my honours teaching; it began with a short unreadable paragraph he composed with phrases gleaned from years of examining PhD theses, and then he proceeded to rewrite it, word by word, seeking brevity and clarity. It was a kind of magic he was performing, shared with generosity and wit. In a review Ken wrote for a newspaper of a book of mine, he noted that I used the word “perhaps” quite often. I wasn’t sure then if it was a compliment. But having read this book called I Wonder — which explores Ken’s speculative intelligence and compassionate questioning — I’m now confident Ken saw it as a virtue. He was a naturally modest man and his insights were offered for reflection and debate; although he was humble, his curiosity was tenacious and life-enhancing. This is a warm, loving book that not only honours Ken but illuminates a generation of historical scholarship, enabling us to see a great historian at work and play, constructing an oeuvre across a whole life. I come from this book invigorated. There is work to do, urgent work, scholarly work, public work. Ken Inglis would expect us to do it — and to help one another to do it. •

Tom Griffiths spoke at the launch of “I Wonder”: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis at Readings Carlton on 10 March 2020.

“I Wonder” is edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark and published by Monash University Publishing. Inside Story readers can purchase a post-free copy at a 20 per cent discount here by using the code PUBGEN20. You’ll be asked for the code on the third page of the ordering process.