Tim Pallas, the treasurer of Victoria, is a lucky man. And if you take Wednesday’s state budget at face value, he is about to share his good fortune with Victorians by finally launching a long-overdue lift in the state’s bonsai-level infrastructure spending.

The 2016–17 Victorian budget is dominated by two things. The first is a huge revenue windfall, largely but not only due to the boom in Melbourne real estate prices and sales. In just two years, the budget forecasts, state tax collections will have shot up 18 per cent, $3.3 billion a year, while GST revenues passed on by the Commonwealth will grow by 16 per cent or $1.9 billion. Federal treasurer Scott Morrison must sigh with envy.

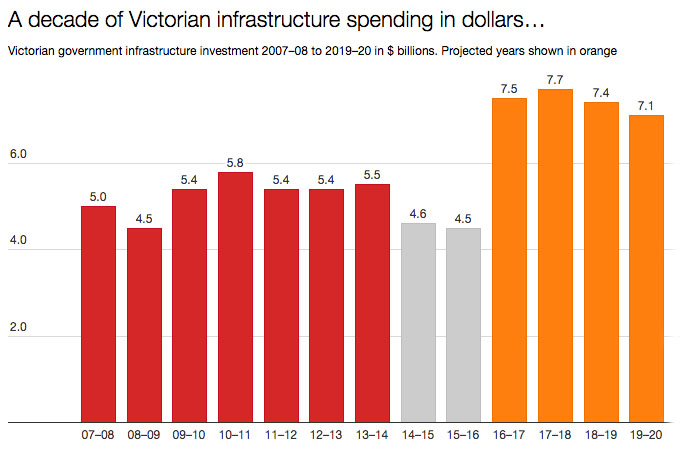

The second is what Pallas presented as a cosmic leap in state infrastructure spending: from $5.2 billion a year on average over the past seven years to an average $7.4 billion over the next four years. And there is more to come; he foreshadowed a further $16 billion over the next decade for new projects that will be chosen after advice from Infrastructure Victoria, the government’s new advisory body.

That wasn’t all Pallas had to offer. Business will get payroll tax relief worth $312 million over four years. The government has committed to investing almost $1 billion in new projects to improve hospitals and health centres, $924 million to build, enlarge or upgrade government schools, an unprecedented $572 million to try to reduce violence in families and shelter its victims, and $596 million to boost police numbers and effectiveness.

These are boom times for Victoria, which is why its treasurer is a lucky man. The lower dollar has boosted Victoria’s key industries, and Melbourne remains the cool place that Australians choose to move to. Last year, the state attracted almost a third of Australia’s population growth, and its growth rate of 1.75 per cent was one-and-a-half times that of the rest of Australia. Total spending in the state in current dollars grew 6 per cent, three times as fast as the rest of Australia. And while Sydney’s meteoric house price boom has finally passed, Melbourne’s is still going strong.

In the financial year just ending, that alone gave the state a $1 billion windfall in stamp duty on top of its forecast in last year’s budget. The government expects that to decline a little ahead, but most of the gains will stay. This year the boom will flow on to land tax, with collections expected to jump 28 per cent as the new valuations take effect. The latest Grants Commission distributions delivered a further $300 million windfall – more evidence that by handing out money on the basis of states’ needs in past years the umpire often kicks them when they’re down, then showers them with money when they no longer need it.

Labor promised voters to always return operating surpluses of at least $100 million a year – that is, revenues will always pay for the services government delivers, with a bit to spare – but in times like these, that’s a low hurdle to clear. Pallas foreshadowed operating surpluses of $2.9 billion in the coming financial year, and $9.2 billion over the next four years, all of which will be ploughed into what was portrayed as record infrastructure spending.

This follows widespread criticism that Victorian governments from both sides have failed to invest in expanding Melbourne’s infrastructure to cope with its extraordinary population growth. The city is growing by almost 2000 people a week, is now a third bigger than it was just fifteen years ago, and, at current growth rates, could house nine million people by 2050.

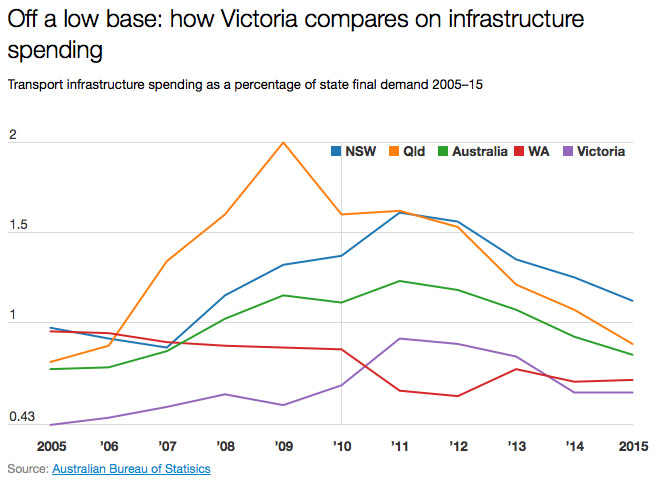

Yet as the chart shows, Victorian government investment in transport over the past decade has been only half the level in New South Wales, a state that has grown far more slowly. Roads, trams and trains have become far more congested, at a cost to the city’s productivity and liveability alike. And while former premier John Brumby recognised this and lifted investment sharply in his last years, since his departure governments of both sides have dragged it back down again.

Now Pallas wants to return to Brumby’s path, with a bang. In the coming financial year, we are told, the state’s investment in new infrastructure will jump from $4.5 billion to $7.5 billion. Investment in transport projects will soar from $2.5 billion to $4.1 billion plus, with funding for some projects still undetermined.

It is a big shift, and a welcome one. But before we get too carried away, let’s unwrap the tricky packaging with which Labor has presented it. Okay, that $7.4 billion average spending in the next four years is a lot higher than the $5.2 billion average of the previous seven years – but the difference mainly reflects Victoria’s population-driven growth in that time, plus a bit of inflation, plus a small genuine shift in priorities.

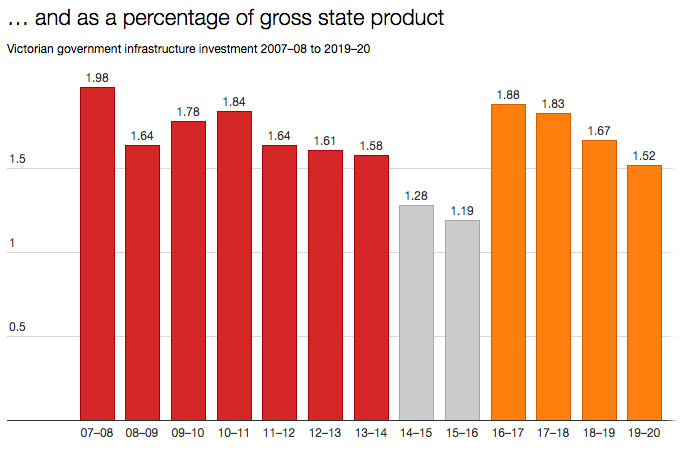

Another way of looking at the same numbers is to take them as a share of the state’s output, or gross state product, or GSP. Take out these past two years, when the Napthine and Andrews governments in turn really dropped the ball, and the figures look very different. In fact, the investment–GSP ratio Pallas is promising for the next four years is 1.73 per cent – which is exactly the same as it was in the seven years from mid 2007 to mid 2014, and below the average level in the four years of the Brumby government.

Source: Department of Treasury & Finance and author’s calculation

So essentially Andrews Labor is simply returning investment to the level it was under Brumby Labor, admittedly with more focus on productivity-enhancing roads and rail, and less on new school buildings and that desalination plant, which was not so useful. Even so, Victoria’s investment in new transport will remain well below NSW levels, or those of the former Labor government in Queensland. It’s a step in the right direction, but not enough to keep pace with a population growing at this rate.

Media analysis of the budget has focused more on the politics of it all. Victoria has long received far less than its share of Commonwealth funding for new roads and rail, but the Abbott government took this to a new level, awarding the state just 9 per cent of transport funding over the five years to 2018, despite its having 25 per cent of the population and even more of the population growth.

This is a bomb waiting to explode under federal Liberal MPs in marginal Victorian seats – yet, surprisingly, Turnbull has made only token attempts to defuse it. Victorian government sources say they had high hopes when he took power and appointed a Victorian, Darren Chester, as infrastructure and transport minister. But protracted talks have failed to produce agreement on any project at all.

Both sides have now resorted to negotiation by ultimatum. On his last trip to Victoria, Turnbull announced to the media that the $1.5 billion already paid to Victoria for the abandoned East West Link should be used for half a dozen other projects – none of which, however, matched what the state was asking him for.

Victorian premier Daniel Andrews has been equally guilty of negotiating through the media. With the federal election looming, he has now widened the gulf by deciding that Victoria will go it alone to fund both the $5.5 billion Western Distributor, Melbourne’s biggest road project, and the $10.9 billion Melbourne Metro, its biggest rail project. The state is already funding all of the third mega-project, its $5 billion–plus plan to remove fifty of the worst level crossings that shut down Melbourne’s roads in peak hours.

Pallas announced the Metro decision yesterday with a statesmanlike, more-in-sorrow-than-anger flourish. “We are not doing this in a belligerent way, we just need to get on and get this [project] done,” he told journalists. “We just can’t wait. Victorians need to know that we are serious about this project, and we need to deliver it, with or without the federal government.”

He added pointedly: “The door is open for any future federal government to come to the party and contribute its share.”

Pallas ridiculed some of Turnbull’s offers to the state – a Commonwealth loan to help it build the Western Distributor, a $10 million grant for it to study how it might capture rising real estate values around the Metro’s stations. The state had already carried out such a study, Pallas said, and it could borrow money itself almost as cheaply as the Commonwealth.

One hopes that the two governments will sit down after the election like mature adults and work out a sensible way for the Commonwealth to pay for its share of Victoria’s huge infrastructure needs. In the meantime, Turnbull has been boxed in, or has boxed himself in, on what could be a serious issue in Victoria if Labor goes hard on it.

The federal government’s own budget papers last year promised Victoria just $1.3 billion for transport infrastructure between 2013 and 2019, compared with $10.8 billion for New South Wales and $7.3 billion for Queensland. Even if Turnbull had offered his extra $1.5 billion in an acceptable way, there would still be a gross disparity that he would struggle to explain to Victorian voters.

In the meantime, the Andrews government will be rolling out the infrastructure. The $4 billion of transport spending this year will include:

- $883 million to remove level crossings

- $782 million for planning and early works on the Metro (a new underground line between the inner northwest suburbs and the inner southeast)

- At least $408 million for new trains, and $221 million for new trams

- $262 million to start building the Western Distributor, a new crossing of the lower Yarra aimed at relieving congestion on the West Gate Bridge

- $233 million to widen the Bolte Bridge, City Link and the Tullamarine Freeway

and many other big projects, including duplicating the rail line to Melton, restoring the long-demolished rail line to outer suburban Mernda, upgrading western Victoria’s rail freight lines and converting them to standard gauge, a big increase in the maintenance budget for regional rail lines, and the start of what could become a big, long-overdue program to duplicate the overloaded main roads of Melbourne’s booming outer suburbs.

Despite appearances, transport is not the only issue in Victoria, but it has become the main one, and it is where the action in this budget is – apart from areas free of partisanship, that is, including tackling domestic violence, building schools and upgrading hospitals, increasing police numbers, and setting up the state’s own job placement service, Jobs Victoria, to help get the long-term unemployed and displaced workers and apprentices into lasting jobs.

In good times, governments tend to focus on how to spend the money, not on reforms. But given the Andrews government’s focus on financing new transport infrastructure, it’s time it asked the future beneficiaries of all that spending to contribute more.

The detail of the budget papers reveals that in 2015–16, taxpayers are subsiding public transport users by:

- $1.05 per trip on Melbourne’s trams

- $3.33 per trip on Melbourne’s trains

- $5.28 per trip on Melbourne’s buses

- $7.95 per trip on regional (non-V/Line) buses

- $23.08 per trip on V/Line trains and buses.

This amounts to an awful lot of subsidy, $2.15 billion of it, in fact. The maximum price for a day ticket on Melbourne public transport is $7.80, and the average price is probably closer to $5. Public transport in Australia’s low-density cities will always need subsidies, but in Victoria, the taxpayers pay 70 to 75 per cent of the bill, and users just 25 to 30 per cent. A train or tram ride is very cheap compared to rival forms of transport. More realistic pricing could do a lot to help Tim Pallas pay for the new infrastructure Labor is planning.

But let us leave the last word to Pallas, the great-grandson of Greek migrants, who closed his budget speech with the words of a beautiful old Greek proverb: “Society grows great when old people plant trees whose shade they will never sit in.” •