Amid the controversies swirling around the citizenship status and personal lives of our politicians, more important but less newsworthy developments pass unnoticed. And even they sometimes have an element of farce.

When a series of disturbing failures in the South Australian TAFE system came to light recently, education minister Simon Birmingham saw an opportunity to embarrass a Labor government in the leadup to a state election. He referred the mess — which had prompted the Australian Skills Quality Authority to suspend qualifications registrations by ten TAFE courses — to a Senate committee.

As a political stunt, Birmingham’s move turned out to be a lamentable failure. The committee, with a Labor–Green majority, had no difficulty in shifting the focus from local failures to the nationwide problems of the vocational education system. It was aided by the fact that nearly all the submissions (including mine, on which this article is based) pointed to systemic failures caused not by individual wrongdoing but by underfunding and a blind faith in market forces.

Vocational education in Australia is in crisis. Traditional on-the-job training, through apprenticeships and traineeships, is in decline. Technical and further education funding has been slashed, leading to the closure of many TAFE colleges and large-scale loss of teaching staff. Billions of dollars have been wasted on ideologically driven experiments in market competition and commercial provision, most notoriously through the rorting of the FEE-HELP system.

The most obvious problems have arisen in the commercial sector itself, where most of the leading large-scale providers have been exposed as essentially fraudulent, exploiting government subsidies and leaving students with worthless qualifications. But the pressure to respond to market competition has also had damaging effects among TAFE colleges. The problems reported in South Australia are consistent with this analysis.

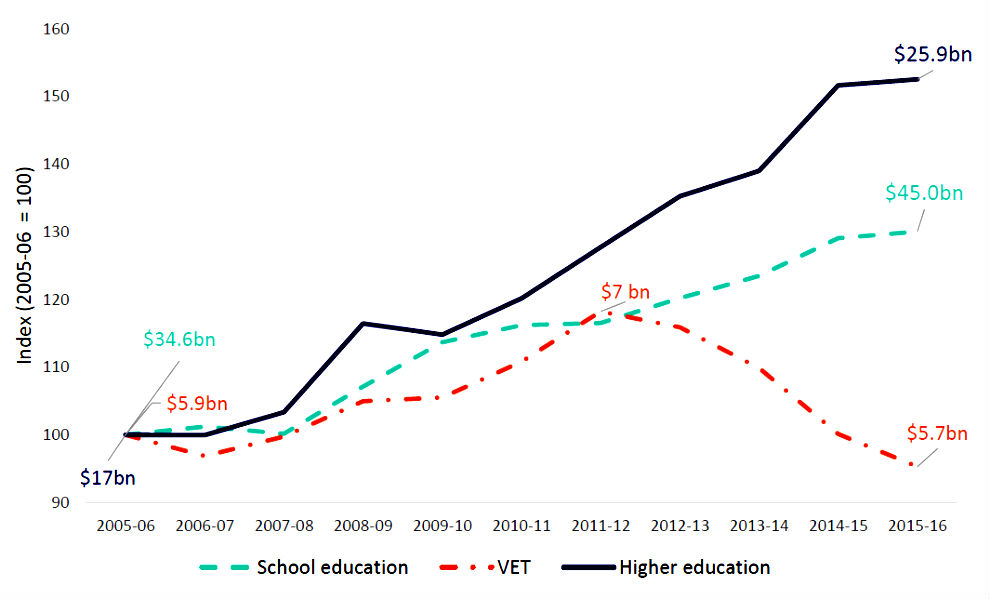

As this chart from the Mitchell Institute shows, funding for vocational education and training has fallen drastically since 2011–12 and is now, in real terms, barely above the 2005–06 level. This is despite an increase in the size of the population, including the eighteen-to-twenty-four age group. And, because education is a labour-intensive activity, real costs have been rising and resources per student declining. Caught in a pincer movement between funding cuts and competition from dubious profit-oriented providers, the sector has experienced a disastrous decline.

Expenditure on education by sector 2005–06 to 2015–16

Base year 2005–06 = 100

Source: Mitchell Institute analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics data

For-profit educational providers have almost invariably failed to deliver good educational outcomes, particular when they have access to public funding. It is far easier to game funding systems than to offer good-quality education. The failures cover all forms of education, from childcare (where the big commercial provider, ABC Learning, collapsed spectacularly, as, more recently, did G8 Education) through to tertiary institutions, most notably in the FEE-HELP fiasco.

The problems were known as early as 2011. In a report published by the National Council on Vocational Educational Research in 2013, I drew on evidence from the Victorian sector to point to the likely failure of FEE-HELP. Many of the initiatives had already been abandoned and others were characterised by chronic problems of fraud and exploitation of regulatory loopholes.

It is now generally admitted that the policy was a disastrous failure. Even the Productivity Commission, in a report advocating more competition in human services, singled it out as an example of what not to do. “Reforms to the vocational education and training sector,” said the commission, “illustrate the potential for damaging effects on service users, government budgets and the reputation of an entire sector if governments introduce policy changes without adequate safeguards.”

Yet the commission’s report gave no indication of how governments might recognise, and mitigate, the potential for such damaging effects, and its own track record of monitoring vocational education and training gives no grounds for confidence.

While it acknowledges the failure of existing policies, the federal government has done little to resolve the crucial problem of funding. Its latest proposal, the grandly named Skilling Australians Fund, proposes that national funding for vocational education should be derived from a levy on temporary work visas and employer-sponsored migrants. Leaving aside the divisive effects of such a policy, the revenue would be manifestly inadequate to address the massive decline in TAFE funding.

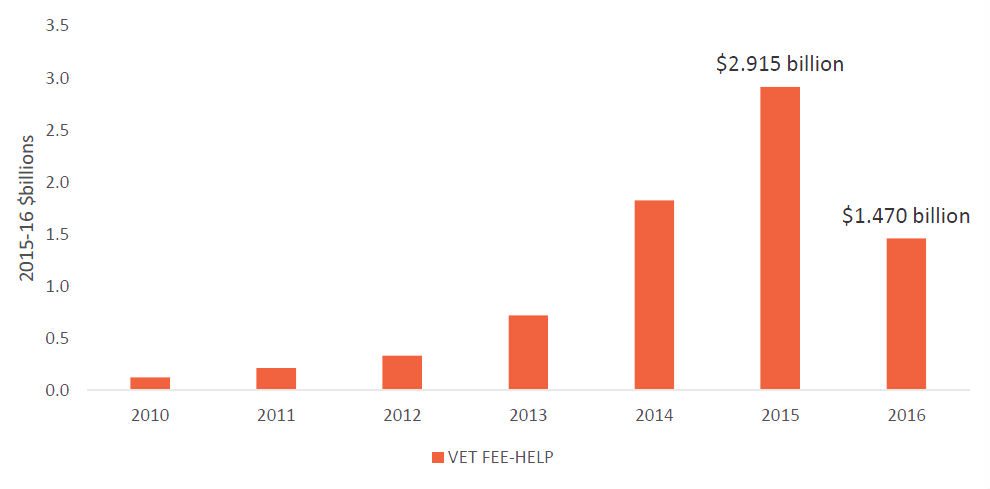

Vocational education and training FEE-HELP payments 2010–16

Source: Mitchell Institute, using VET FEE-HELP Statistical Reports

Universities have been subject to many of the same pressures but have resisted more successfully. The performance of for-profit universities has been very poor, just like their counterparts overseas, and drop-out rates are high. Attempts to convert existing universities to a commercial model — Melbourne University Private and Universitas 21 are the best-known examples — have been significant loss-makers.

Yet the current government has persisted in its attempts to cut funding and promote a variety of initiatives under the label of “deregulation.” These policies threaten to have the same disastrous impact on university education as we have seen in vocational education and training.

Is there a better way? To begin with, we need to recognise that school education alone is not a sufficient basis for participating in the modern workforce or in increasingly technologically sophisticated study. The class division between “vocational education and training” for the working class and “higher education” for the middle and upper classes is inappropriate and unworkable. Commercial education and training should have at most a marginal role and should not be subsidised through student funding schemes such as FEE-HELP and VET Student Loans. Non-profit and community providers should receive adequate funding, as should TAFE.

All young Australians should be encouraged to undertake some form of post-school education and training. And the two sectors — vocational education and training, and higher education — should be combined into a single national system, funded by the Commonwealth.

Those are long-term objectives. The crucial short-term need is for a reversal of the massive cuts in funding to TAFE, and the end of subsidies to commercial providers. If those providers are to remain in the system, they should either stand on their own feet or provide courses under contract through the TAFE system.

The experience of the past decade shows that the problems in the South Australian TAFE system are merely symptoms of failed policies designed by state and federal governments. They should be reversed urgently. ●